As memorials are objects of public commemoration, we demand a lot of them. They serve as testaments to lives lost, as repositories of grief, and to facilitate processes of mourning. We expect them to do the work of history writing, to draw single comprehensible narratives out of a Gorgon’s nest of individual, often contradictory, experiences. These meanings serve as unifying forces, reinforcing the idea of a shared national identity and healing rifts in the communal experience of nationhood.

By endowing memorials with the ability to accomplish these tasks, we bestow them with an extraordinary amount of power and authority. Thus, it is unsurprising that the first skirmish of the culture wars of the 1980s can be traced back to the public debate that broke out in reaction to Maya Lin‘s design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Following its dedication, Lin’s memorial quickly became the prototype for American war memorials. Thirty years later, it is difficult to think of her memorial as a controversial work of art. By now, we are so accustomed to its visual rhetoric—the polished black granite, the lists of names, the horizontal positioning—that to think of these components as anything but standard practice takes an act of real imagination.

However, the years that saw the memorial’s proposal, design, and construction—1980 to 1982—coincided with a momentous shift in the topography of American political culture: the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 and the ensuing negotiation of a new federal agenda. This development was shaped by the theories of economic neoliberals on the one hand and by the values of their socially conservative allies on the other. Far from being a fait accompli, amassing the public will to support this new agenda took real work. In large part, this was accomplished through a series of conflicts waged at the level of culture. The earliest of these battles was the controversy over Lin’s design. Revisiting the terms of this conflict not only provides insight into how and why visual art came to be so politicized in the 1980s, but also sheds light on the debates of our present historical moment, which, in many ways, parallel the debates of that period regarding the social purpose of art.

Though its location on federally owned property and its maintenance by the National Park Service might imply otherwise, the impetus to create the Vietnam Veterans Memorial came entirely from the private sector and from one man in particular: Jan Scruggs, a Vietnam veteran who had been wounded in the line of duty. In March 1979, inspired by the Hollywood film The Deer Hunter, Scruggs launched a personal crusade to raise funds for a memorial that would pay tribute to the soldiers who had lost their lives in the war. In July 1980, Congress passed a bill authorizing three acres on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., to serve as the memorial site. In the Rose Garden of the White House, immediately following President Jimmy Carter’s signing of the bill, Scruggs explained to the press the vision of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF), the non-profit organization that collected and administered the funds for the memorial. “We do not seek to make any statement about the correctness of the war,” Scruggs said. “Rather, by honoring those who sacrificed, we hope to provide a symbol of national unity and reconciliation.”1

Shortly after the dedication of the land for the memorial, the VVMF announced an open competition for designs for the memorial itself. It distributed an instructional booklet communicating its vision to all who registered for the competition. Descriptions of the desired qualities for the memorial design included “harmonious,” “contemplative and reflective,” and again, “conciliatory.”2 The booklet concluded with the following passage:

Finally, we wish to repeat that the memorial is not to be a political statement, and that its purpose is to honor the service and memory of the war’s dead, its missing, and its veterans—not the war itself. The memorial should be conciliatory, transcending the tragedy of the war.3

Both Scruggs’s and the VVMF’s statements clearly conveyed that the memorial the veterans sought was to be an apolitical tabula rasa that would neither contribute to nor comment upon the unresolved controversies surrounding the war. A tabula rasa upon which individuals could project their individual, personal experiences of the war was what the VVMF desired and, as historian Marita Sturken and others have observed, a tabula rasa was what they got.

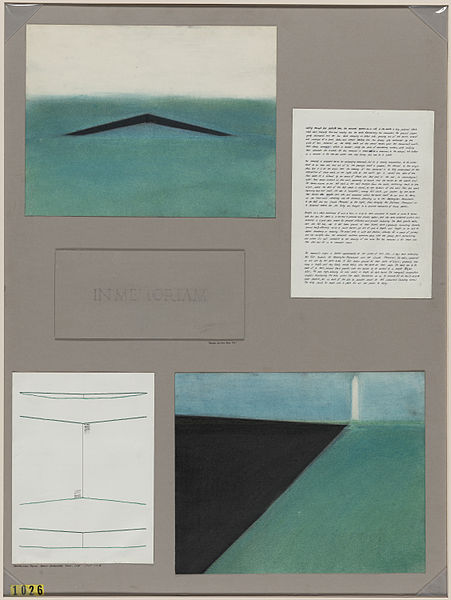

Maya Lin’s original competition submission for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Architectural drawings and a one-page written summary, 1980 or 1981.

Out of the nearly fifteen hundred entries in the competition, the eight jurors of the selection committee unanimously chose Maya Lin’s design on May 6, 1981. Free of overt historical reference to either the Egyptian or Greco-Roman traditions of monument design—the main visual touchstones for American memorial-building—Lin’s design broke with these traditions through its use of black granite, polished to a reflective smoothness (instead of white limestone or marble); its horizontal orientation, submerged into the earth instead of rising vertically; and its lack of any figurative ornamentation or any embellishment at all, save for the chronological listing of names of soldiers killed in the course of the war, etched into the granite’s mirror-like surface.

Despite the stated wishes of the VVMF, Lin’s design proved instantaneously divisive. Many veterans, politicians, critics, and the general public read its refusal to explicitly glorify the war or frame the listed soldiers’ sacrifice in recognizably heroic terms as an ideological statement, proof of Lin’s—and the memorial’s—purported anti-war position. Its detractors perceived it as “a monument to defeat, one that spoke more directly to a nation’s guilt than to the honor of the war dead and the veterans,” describing it as the “black gash of shame,” the “degrading ditch,” and a “wailing wall for draft dodgers and New Lefters of the future.”4 Responding to its lack of narrative content, Senator James Webb called it “nihilistic.” Interestingly (given their opposing political positions), both the National Review and the New Republic equated the list of names with a police report on a traffic accident. The National Review commented, “The mode of listing the names makes them individual deaths, not deaths in a cause; they might as well have been traffic accidents.” Similarly, the New Republic opined:

It is an unfortunate choice of memorial. Memorials are built to give context and, possibly, meaning to suffering that is otherwise incomprehensible. We do not memorialize bus accidents, which by nature are contextless, meaningless. To treat the Vietnam dead like the victims of some monstrous traffic accident is more than a disservice to history; it is a disservice to the memory of the 57,000.5

Furthermore, the extreme visual simplicity of Lin’s monument made it easy for critics to utilize it in a concurrent debate about the merits of minimalist sculptures as public artworks. Despite the fact that beyond certain superficial qualities, Lin’s memorial shared little in common with the work of classic Minimalist artists such as Richard Serra or Donald Judd, critics nonetheless conflated it with Serra’s equally controversial Tilted Arc, labeling it another example of an inscrutable Minimalist public artwork erected at taxpayers’ expense. The debate over Minimalism, applied to Lin’s design, provided new terms through which to resurrect America’s internal debate over the validity of the Vietnam War. It also offered a way to exorcise lingering bitterness and anxieties that the war had propagated. For example, veteran Tom Carhart famously commented:

I don’t care about artistic perceptions, I don’t care about the rationalizations that abound. One needs no artistic education to see this design for what it is, a black trench that scars the Mall. Black walls, the universal color of shame and sorrow and degradation. Hidden in a hole in the ground, with no means of access for those Vietnam veterans who are condemned to spend the rest of their days in a wheelchair. Perhaps that’s an appropriate design for those who would spit on us still. But can America truly mean that we should feel honored by that black pit?6

Like many veterans, Carhart read Lin’s design through the lens of his own experience: encountering an America that was at best indifferent and at worst outright hostile towards soldiers returning from Vietnam. Furthermore, he explicitly framed his interpretation of the memorial in (perceived) opposition to an explicitly “artistic” perspective. Carhart equated artists and their defenders with individuals who engaged in acts of aggression against returned soldiers, and who were thus correlated with the entirety of the anti-war movement. Critics of Lin’s design proposed that a second work be included on the memorial site, as a solution to the problem of the original memorial design: a figurative bronze statue by Frederick Hart of three soldiers in uniform, which had placed third in the initial competition. Lin vociferously objected to the inclusion of Hart’s piece, arguing that it violated the “integrity of [her] design” and created the sensation of “being watched,” as if one were on a “golf green.” As Sturken points out, this did little to evoke veterans’ sympathy: “Lin stuck to her position as an outsider . . . while the veterans were primarily concerned with the ability of the design to offer emotional comfort to veterans and the families of the dead, either in terms of forgiveness or honor.”7

Social critics and commentators quickly picked up and elaborated on Carhart’s characterization of the memorial. In an article in the Washington Post, writer Tom Wolfe defined the debate over the inclusion of Hart’s figurative memorial as a “story of art experts and the Vietnam veterans—and of how the veterans asked for a war memorial and wound up with an enormous pit they now refer to as a ‘tribute to Jane Fonda.'” Continuing, Wolfe sarcastically asked:

Shouldn’t public sculpture delight the public or inspire the public or at least remind the public of cherished traditions? Nonsense. Why reinforce the bourgeoisie’s pathetic illusions? […] Over the past two months, art mullahs of every description have begun a holy war against the addition of [Hart’s] statue.8

Another article in the same issue of the Post echoed Wolfe’s definition of the terms of the debate, commenting that:

There is a discordance between the sophisticated wall and the unsophisticated statue. There is also disharmony between the nay-saying wall and the unequivocally proud flag […] And nothing has happened to make Maya Lin’s creation look less like what it suggests to some veterans and some non-combatant citizens: ‘an open grave.'”9

Ultimately, the Commission of Fine Arts, which had the final say in the matter, overruled Lin’s objections. Not only was Hart’s statue included at the memorial site, but a flagpole was added as well. Jan Scruggs’s and VVMF members’ desire for a memorial that would heal the social rifts wrought by the war was wishful thinking. Instead, the memorial became a dividing line between factions both real and imagined. On one side were the proponents of Lin’s memorials, defined in the media and the public imagination as Wolfe’s elitist “art mullahs,” “draft dodgers,” the “future New Leftists,” and, of course, followers of Jane Fonda (infamously dubbed “Hanoi Jane” after a trip to North Vietnam, during which she made statements condemning the U.S. military). On the other side were the veterans and their self-appointed spokesmen, politicians such as Webb and James Watt (Secretary of the Interior under Ronald Reagan), and social conservatives such as Pat Buchanan.

This alliance between the veterans and their conservative defenders was a new one, forged as a direct result of the cultural battle over the memorial site. For years, American society as a whole, regardless of political affiliation, had studiously ignored Vietnam veterans, their presence a painful reminder of the war’s moral ambiguity. At the time of the memorial’s design, many veterans who had been exposed to Agent Orange, a chemical weapon used by the U.S. military as an herbicide and defoliant, still suffered ongoing health problems. The Veterans Administration hospital system was underfunded and ill-equipped to help Vietnam veterans deal with either their physical ailments or the psychological challenges of post-traumatic stress disorder. In fact, throughout the 1970s, there was little political impetus on any front to address these shortcomings.

While many veterans successfully reintegrated into their families and communities, tucking their experiences in combat away on a mental back shelf, others were unable to cope on their own. Lacking sufficient services to assist their recovery, some of these unassimilated veterans turned to alcohol and other drugs, their addictions only sending them further to the margins of society. As Michael Clark points out in the essay, “Remembering Vietnam,” by the late 1960s, Hollywood and the mass media seized on this aspect of the veteran experience, creating variations of a fictionalized veteran “who threatened at every moment to bring the war home with him in the form of flashbacks that turned firecrackers into artillery and passersby into the enemy.”10 In Clark’s analysis, these depictions of veterans served, for nonmilitary American citizens, as a way to “launder the violence of the war by relegating it to some ‘other’ place: Southeast Asia, and the [veteran’s] psychotic unconscious.”11 Such representations enabled film viewers to reframe their experiences of the contemporaneous violence occurring at home, on American soil. Traumatic memories—such as those of police officers brutally beating anti-war protesters at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago and members of the National Guard opening fire on students protesting the war at Kent State University in Ohio—were removed, like a tumor, from the body of the nation and assigned to another geographical location: Vietnam.

These mass-media fictions enabled the very real neglect of veterans by the institutions tasked with tending to their needs. Consequently, by the time of the memorial’s design and construction, veterans had built up a significant amount of moral outrage and found their outlet in the controversy over the memorial. As the commentaries of Wolfe, the New Republic, and the National Review demonstrate, the media was happy to add fuel to the fire of the veterans’ indignation through editorial contributions and obsessive coverage of the debate. However, the media was not the only entity invested in the veterans’ compelling predicament. Ronald Reagan’s election in November 1980 ushered in the “Reagan Revolution,” and the first few years of Reagan’s presidency saw the largest tax cuts in American history. Significant funding cuts to programs that had been instigated in the 1960s under Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” domestic agenda followed, in addition to a major attack on union power. Reagan’s 1981 inaugural speech exemplified the political rhetoric used by his administration to promote his vision to the American public. Heralding the end of one era and the commencement of a new one, Reagan famously proclaimed, “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem,” further adding that:

From time to time, we have been tempted to believe that society has become too complex to be managed by self-rule, that government by an elite group is superior to government for, by, and of the people. But if no one among us is capable of governing himself, then who among us has the capacity to govern someone else? All of us together, in and out of government, must bear the burden.12

Daniel Libeskind. Memory Foundations (planned design for former site of World Trade Center in lower Manhattan, New York).

This message of personal responsibility, in contrast to governance by “an elite group” on behalf of individuals, became a hallmark of the Reagan administration. It set the tone for the ensuing cultural debates pitting “the people” against “the elites,” as found in Tom Wolfe’s criticism of Lin’s memorial design. As conservatives sought to consolidate their gains following Reagan’s election, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial controversy presented an opportunity for conservatives to harness both the affective power of the veterans’ fury and the resulting public outcry on their behalf.

Following a march by thousands of veterans through the streets of Washington, D.C., to the National Mall site, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated on November 13, 1982. The controversy surrounding the memorial instantly vanished from the pages of the press, replaced by celebrations of its interactivity, tranquility, and emotive power. Once there was no more room for conflict—the memorial’s form, upon dedication, was no longer negotiable—the front in this culture war moved elsewhere. The shift, however, did not represent a resolved conflict between public art and public memory and memorialization, but merely a temporary relocation of the site of debate.

The controversy over the planned 9/11 memorial at the former site of the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan, which began nearly a decade ago, harkened back to the debates of the early 1980s and heralds the current resurgence of cultural warfare. As Sturken notes in her essay, “The Aesthetics of Absence: Rebuilding Ground Zero,” the impetus to create a memorial at the site of the Twin Towers was “almost instantaneous—by the next day, even as the names and number of dead remained unknown, there was discussion of a memorial.”13 Discussions about what to do with the site addressed two twin concerns: the redevelopment of what had been both a hub of commercial activity and an integral part of a broader residential neighborhood—lower Manhattan—and the memorialization of the loss of lives that occurred at the site. The number of parties who claimed direct investment—whether emotional, psychological, or financial—in the site and its future form and use only made the issue more complex and difficult to resolve. The fact that such nongovernmental entities as the New York Times, CNN, and the Max Protetch Gallery took it upon themselves to solicit designs for both the new World Trade Center buildings and for suitable memorials to the attacks indicates the extent to which the American public writ large was attuned to the site’s future.

In response to the designs submitted to these various competitions (generated by famed architects, artists, and members of the general public alike), conflicting interpretations once again revolved around notions of elitism versus populism——harkening back to the language of the controversy over Lin’s memorial.14 In a 2002 debate with architect Daniel Libeskind on the matter, New Republic literary editor Leon Wieseltier commented, “There is something a little grotesque in the interpretation of Ground Zero as a lucky break for art. Lower Manhattan must not be transformed into a vast mausoleum, obviously, but neither must it be transformed into a theme park for advanced architectural taste.”15

Such rhetoric spilled over from the initial debates surrounding the redevelopment of the site of the Twin Towers to those regarding the design for the memorial. Having chosen Libeskind’s overarching vision, titled Memory Foundations, in February 2003, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (tasked with coordinating the redevelopment of lower Manhattan and administering the nearly $10 billion in federal funds devoted to supporting that effort) two months later announced the memorial design competition. In November 2003, the LMDC placed the proposals of the eight finalists on display for public review.16 According to Sturken and art historian Anne Swartz, criticism of the designs, including that of the eventual winner, Peter Walker’s and Michael Arad’s Reflecting Absence, revolved in large part around their perceived minimalist aesthetic, once again drawing on the rhetoric involved in the Tilted Arc debate. Some observers attributed this factor to Maya Lin’s presence on the jurying panel, which also included victims’ families, political appointees, curators, and other artists.17 It was even announced at one point that Walker’s and Arad’s design resembled a sketch that Lin had made for the sort of memorial that might be placed at the site.18 Like Lin’s design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Reflecting Absence was criticized for failing to incorporate any representations of human figures, its minimal design interpreted as “a rejection of codes of heroism.”19 In a practical reenactment of the negotiation of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the addition of a representational statue of three firefighters hoisting a flag at Ground Zero was proposed. The plan, however, was eventually scrapped, once the initial haggling over the racial identity of the firefighters gave way to accusations of “political correctness” on the part of the memorial’s planners.20

Peter Walker and Michael Arad. Reflecting Absence (planned design for memorial to victims of attacks on the World Trade Center, September 11, 2001).

Perhaps Lin’s centrality—twenty years after the construction of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—to the debate over Arad’s and Walker’s design was inevitable, given her presence on the design competition’s selection committee as well as her legacy as the definitive memorial builder of the late twentieth century. But the fact that the language deployed to critique Arad’s and Walker’s design so closely echoed the criticism launched against Lin in the early 1980s signifies that the debates of that era remain unresolved. Additionally, the emergence of Park51—the proposed Muslim community and cultural center to be located a few blocks from the former World Trade Center site—as a major point of public interest and debate, which peaked during the 2010 congressional elections, confirms the continued political potency and cultural power of memorials as embodiments of representational practice.

1. Karal Ann Marling and Robert Silberman, “The Statue Near the Wall: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the Art of Remembering,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art 1, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 10.

2. Daniel Abramson, “Maya Lin and the 1960s: Monuments, Time Lines, and Minimalism,” Critical Inquiry 22, no. 4 (Summer 1996): 685.

3. Ibid.

4. Marita Sturken, “The Aesthetics of Absence: Rebuilding Ground Zero,” American Ethnologist 31, no. 3 (August 2004): 122.

5. Marling and Silberman, 11.

6. z”The Vietnam Wall Controversy, Round 3, October 1981–January 1982,” History on Trial, Lehigh University Digital Library, accessed April 21, 2011, https://digital.lib.lehigh.edu/trial/vietnam/r3/october/.

7. Sturken, 125.

8. “The Vietnam Wall Controversy, Round 4, 1982,” History on Trial, Lehigh University Digital Library, accessed April 21, 2011, https://digital.lib.lehigh.edu/trial/vietnam/r4/1982/.

9. Ibid.

10. Michael Clark, “Remembering Vietnam,” Cultural Critique 3 (Spring 1986): 50.

11. Ibid.

12. “First Inaugural Address (January 20, 1981), Ronald Wilson Reagan,” Miller Center For Public Affairs, University of Virginia, accessed April 21, 2011, https://millercenter.org/scripps/archive/speeches/detail/3407.

13. Sturken, 321.

14. Sturken, 320.

15. Ibid.

16. Sturken, 322.

17. Sturken, 322; Anne Swartz, “American Art After September 11: A Consideration of the Twin Towers,” Symploke 14, nos. 1–2 (2006): 95.

18. Swartz, 95.

19. Sturken, 322.

20. Ibid.

Editor’s note: This essay was originally published on Art21.org in November 2011.