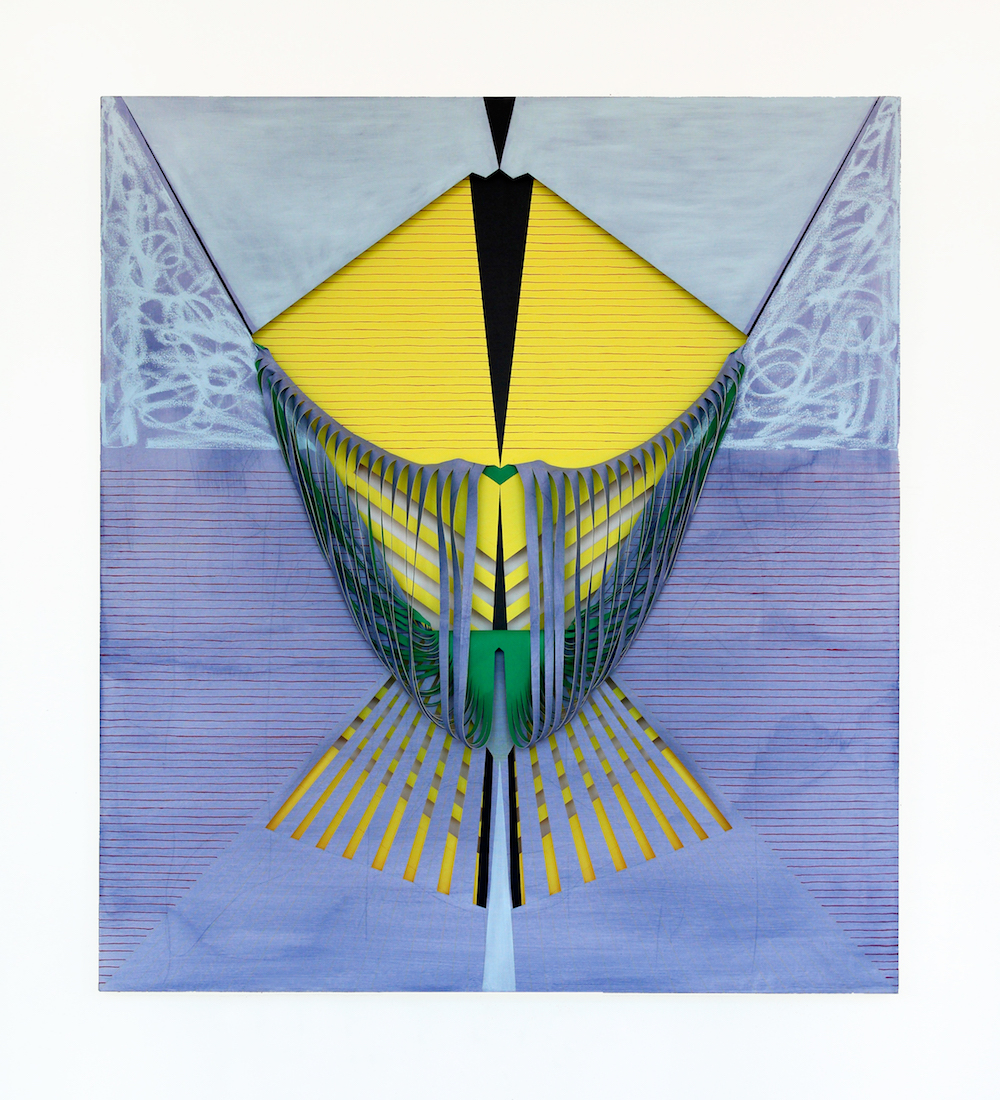

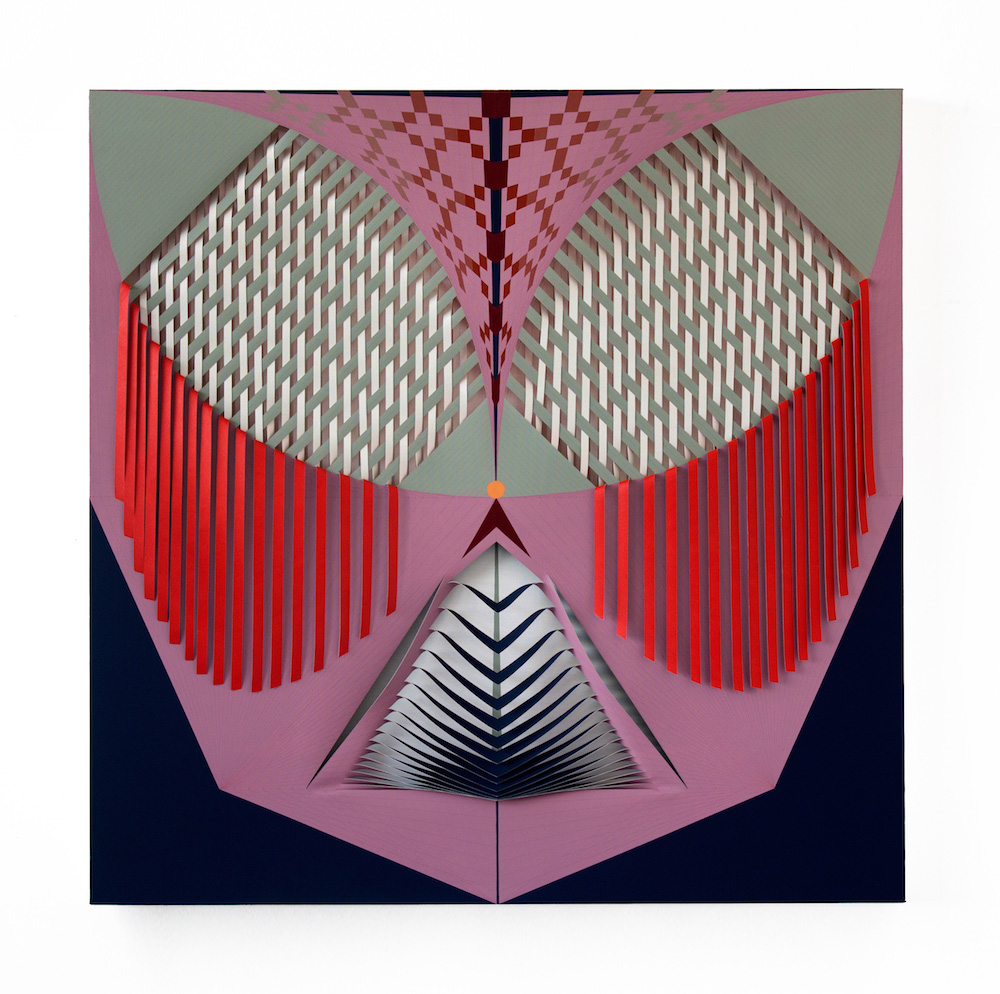

While preparing for an exhibition, Cristina Camacho read Haruki Murakami’s novel, The Wind Up Bird Chronicle. She said: “I came across a sentence that caught my attention. It was about the very simple idea that you will never be able to see your own face; your perception of yourself will always be filtered through a mirror, a photograph, or other people’s descriptions. But in spite of that, it is through your face that you are recognized.” This became the central concept for Camacho’s recent works: an exploration of identity that employs a recurring metaphor, that of the canvas as a living organism. “I use the canvas to explore the idea of symmetrical balance that is usually associated with the face,” she said. “We think of ourselves as being symmetrical, but in reality your face is never the same on both sides. I’m interested in exploring the balance between symmetry and asymmetry in the human face.” In her new large-scale paintings, Camacho continues her practice of cutting and weaving the canvas to produce anthropomorphic figures, but in these works, she goes beyond an exploration of the body. “When you see a face, you sort of attribute to it a personality, automatically. I feel like you are giving it a life. When people used to look at my paintings, they would see parts of bodies or flowers, but now they usually associate them with a feeling or mood.” Camacho’s new works are an attempt to create a visible window through which we might access the invisible human soul.

Born in Bogotá in 1987 to a family in the textile industry, Camacho grew up doing needlepoint and embroidery with her mother. Her craft-based background led her to study design in the Universidad de los Andes before coming to New York with the intention of exploring different artistic mediums and materials. “I never thought of myself as a designer, but I do think that there are certain things that I learned from [design] that are still present in my work, like the use of color.” As an MFA candidate at Columbia University, she was able to incorporate all the skills she had acquired into a single body of work. “When I first started cutting up the canvas, I was very consciously trying to distance myself from being categorized as another Latin American artist doing abstract art. But at the same time, I was doing a lot of symmetrical work and the cuts were very controlled.” When she was working on the painting, Feeling Purple (2014)—which was featured in her previous show, Bilateral Dissections—she realized how to listen to the material. “I was finally able to understand that you have to let the material be, with all of its qualities and defects. It has to be able to respond to gravity; it needs to be able to rip and to [show its] weight. At first, I was trying to domesticate the material, but I finally saw it as a living being.” By treating the canvas as a skin, Camacho realized that giving the material the agency it deserved might limit her own. “I looked at that painting and realized it was doing exactly what skin does: it falls and it ages, and there is nothing that I can do about it.”

This relinquishing of control makes balance a crucial element of Camacho’s work, both formally and conceptually. “The name of my most recent exhibition was Bilateral Dissections because I see the works as bodies that have a bilateral symmetry; the right and left sides are the same, and there is a vertex that divides the paintings horizontally.” The works present a natural tension that comes from the cutting and weaving of the canvas, which requires a careful exploration of opposites. “I am constantly searching for the middle point between law and chaos. The materiality of my paintings requires that there be established laws; there are geometric grids and measurements that I have to follow, but they are interrupted by the cuts.” Camacho’s work is the result of a structured process that allows room for error and improvisation. “Learning to deal with the errors that come with [my developing] relationship to the canvas generates my work. It is a mutually productive process, in which both I and the material bring something to the piece.”

Tracing the Out of Sight is on view through May 27, 2017, at Praxis Gallery in New York City.