This roundtable discussion occurred at Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum in Detroit with the following participants: Taylor Aldridge, Assistant Curator, Detroit Institute of Arts; Olayami Dabls, artist and founder of Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum; Carole Harris, fiber artist; and Laura Mott, Curator of Contemporary Art and Design, Cranbrook Art Museum.

Laura Mott: For the theme of an Art21 Magazine issue, Taylor and I wanted to select a material, because our previous research together and separately concerns the material culture of the city of Detroit. Rust seemed like an interesting topic to dive into since it is a byproduct of the city’s industrial history. It is frequently used in your respective practices [Harris and Dabls] both as a material and as a metaphor. Dabls, I think it would be interesting if we began with the origins of your outdoor installation, Iron Teaching Rocks How to Rust (1998–ongoing).

Olayami Dabls: From 1975 to 1985, I worked at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History (it had a different name back then). There was a room full of books on African material culture, and those books talked a lot about iron. It was the first time I had ever heard anyone talk about iron on the same level as diamonds and gold. It was the first time that I had heard anything about the iron revolution in Africa, which occurred long before the industrial revolution in this country. With iron, Africans were able to make these incredible tools, but iron would rust; it would deteriorate. I noticed here, in the West, anytime rust was seen, people would put some kind of paint over it to try and stop it. But rust would come from the inside out. When I moved here to the African Bead Museum, I wanted to do some outside work, but I needed a theme; I needed it to be more than art for the sake of art. So, one day I was out there in the field, and I picked up this rock that had a piece of iron protruding out of it. The iron had stained the rock, and I thought, “The iron taught the rocks how to rust.” That was the genesis of the metaphor and the use of iron. Iron is something visible that can literally be killed over time by air, which you can’t see. That fascinated me. And in my metaphor, if iron teaches something how to rust, then I’m teaching something how to decay. It was all tied to culture: if I align with someone else’s culture, different than my own, that’s deteriorating it [one’s own culture].

When I worked at the Wright Museum, it was focused on the civil-rights decade, from 1955 to 1965. Most of the people I was giving tours to had experienced some aspect of that in the community, and I was always being told, “That’s not how it happened in my neighborhood.” I knew what they were talking about, because history isn’t an agreed-upon story. And if one is not at the table, in agreement, one gets left out. I wanted to tell a story without any interruptions, so I got the idea to use metaphor. In African culture, the best way to teach is through metaphor, so that’s how I was using iron and rust.

Carole Harris: I have a metaphor, too; I just came about it slightly differently. It’s also about materiality. I was born in Detroit, so I’ve been looking at the city’s landscape for many years. And for the past twenty years, I’ve been documenting and researching the landscape and how it changes. I’ve always worked with fiber; rust only recently entered the work in the past five years. There are things I know now that I wish I had known then. I’m glad I took a lot of the photographs that I did, because many of those places are gone now. But in recent years, I noticed that often people come and take photos of buildings and things around Detroit, calling it “ruin porn.” I didn’t see my city as a ruin. I saw buildings that were in disrepair and maybe abandoned, but I also saw layers, as things were being stripped. At that same time, I became introduced to and enchanted with the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, the embrace of imperfection. That’s the way I thought of these buildings. I thought that they held stories, history, and culture—that they talked about people’s lives. And so I used that as a metaphor for life, not just for the city of Detroit.

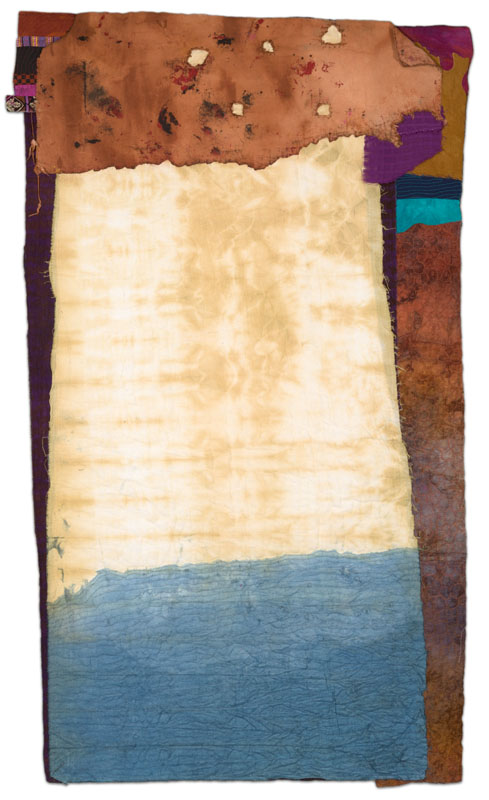

And like Dabls said, people were always painting over rust. Through my travels, I found that [practice] didn’t happen around the world. Other people weren’t so ready to cover up what’s natural, whether it’s a building environment or natural environment. Things do break down and erode, and I saw a kind of beauty in that erosion—you know, letting things be as they want to be or return to what they really are. So, I guess I’m teaching cloth how to rust. [Laughter]

I was really more interested in the marks that time makes, whether it [be] on the built or natural or personal environment. You may see a woman who has some wrinkles and is a little stooped, but you know she was a really beautiful woman at one time. If you take the time to scratch the surface, there are a lot of layers there. And that’s what I saw in these buildings. You don’t get the whole story by looking at the surface; you have to dig deeper. So I’m doing that in my cloth. Right now, I’m interested in the materiality, trying to show these layers; they become more coalesced and the metaphor becomes clearer.

Taylor Aldridge: In addition to metaphor, ritual is another word Laura and I have been tossing back and forth throughout our research, and ritual seems to be a big part of each of your practices. Whether you are going on a walk and collecting these scraps or doing an outdoor installation project over several decades, there’s a sort of ritual involved. Can you talk about the rituals that are incorporated in your work and how they’ve evolved or changed over time?

CH: Well, I don’t think about it; I just do it. I collect things, and I never know what’s going to happen with them. I have these bottle caps that I think at some point are going to be stitched into some fabric. Every day that I’m out in Detroit and looking, I see more possibilities. Then I get back to the studio and think about how I’m going to use [found material]. I’m not trying to duplicate what I see in the street. The material speaks to me in a different way: how to actualize the transfer, to make this into another form.

OD: I prefer the word tradition, using something from a historical perspective. My work involves the continuation of how Africans use iron and the by-product of iron, the rusting process. Iron had a very special place in African cultures. The people may not have spoken the same language, but they approached the use of iron similarly. Iron was seen as magic and medicine. There are some things you can prove through science, like there is enough iron in each one of us to make a three-inch nail. We can’t live without iron. Blood is its color because of iron. Because iron has magical qualities—all people on the planet are connected to iron—I decided to use iron in an installation to see if it would attract people from all over the world.

I’m using traditional materials—iron, rocks, wood, and mirrors, found in all African cultures—that are used to protect, purge, and offer help to the people. Every piece of art that I make will feature these materials in some fashion because they have properties that communicate to the world; all ancestors and memory are connected to those materials. I use iron traditionally, through initiation rites.

A Nkisi is any vessel that one can put herbs in. I have a Nkisi, at that house across the field. Iron, rocks, wood, and mirrors are the potions that I put in it, seven years ago. When I did this, I asked the Nkisi to prevent three things: graffiti artists from tagging it, vandals from vandalizing it, and the city government from seeing it. And none of those events has happened. So, I’m using traditional customs and materials that our ancestors used, and it comes across as being part of the present, of what’s going on now. Tradition follows you; sometimes you don’t even have to be aware of doing things in your tradition.

CH: It’s sort of like a cultural memory.

OD: [Carole’s rusted cloths] remind me of tie-dye, which was being done pretty much all over Africa. No one can be completely cut off from culture. But if I can get someone to study somebody else’s culture and point of view, then I can get that person to suppress the deterioration. One’s personal part of the culture is passed on at the moment of conception.

CH: Both of us are involved in working with rust, with these traditional materials—witnesses to the fact that other bits have been suppressed.

LM: Let’s talk about time and duration. For instance, Carole, you come from a quilting tradition, which is a durational act, a dedication of time. The process of making a quilt has a parallel to rusting, in how it takes shape and forms over time. How do you both see time as an element in your practices?

OD: I’m not trying to create something that will last forever. I know that with the effects of sun, wind, snow, and rain, an aesthetic will appear that is as exciting as the fresh paint, wood, and the iron. So, I never concern myself with trying to keep a material the way it originally was. And that is built in because I’m working outside with materials that will naturally deteriorate. Mirrors will fade behind the glass; the sun pulls that off. The iron deteriorates in front of me, and the paint changes color. I welcome those changes, as opposed to trying to keep what a material first looked like, years ago.

CH: With my work, time is a place to begin—the way that something evolves and looks, not only the rusting process but also the tearing. What’s interesting about time is the idea of where something comes from. Now I’m mostly doing hand stitching, which is also a statement about time: it requires that you sit there and do it. To make this has become a meditative process. It’s right for what I’m doing with the cloth, too: it’s about the impact of time.

TA: The parent of rust is iron, which is prominent in Detroit’s automotive industry. Could you each talk about your history with the industry and how that has influenced your work?

OD: I went to Highland Park Community College, and I got an associate degree in drafting. At the time, General Motors asked my professor to recommend some students to its [company] school, which mostly trained engineers. So I started at General Motors as a mechanical engineer. Prior to that I was making springs for cars. After working for General Motors, I studied mechanical engineering at Wayne State University, with a minor in art. I was in an automobile accident and stayed in the hospital for almost three years with a major back injury. With hindsight, I think that period meant my brain was just getting me ready to do something else. Pay attention to your brain; it’s a powerful piece of machinery.

At that time, there were different rules, if you were an African American: you couldn’t do art; you stayed away from that. It was segregated. But Wayne State had an open policy, which let you go ahead and do what you wanted to do. So I transitioned from mechanical engineering to fine art, the opposite end, where I could just do what I wanted. When I’m doing art, the [back] pain is gone.

TA: Similarly, Carole, you have a very technical background as an interior designer. Can you describe the transition that pulled you out of that and into a fine-arts practice?

CH: I just wanted to be an artist and paint, but there was no way I was going to find a job doing that. For a year I studied interior architecture and learned how to draw mechanically and learned about construction. I was able to get a job upon graduation, but that was just so I could eat and have a roof over my head.

The first job I had was at J. L. Hudson [department store], which was blatantly racist about what I could and could not do. And I made noise about it; I wasn’t the ideal employee. I left to join Bill [Harris], and we got married. In 1968, I did some work for Hudson’s; things were a little different then because the riot had happened, the rebellion had happened, and [the company claimed to] offer more opportunities for African Americans. I went to a different department and learned about commercial design, which led me to [work at] Albert Kahn.

Then I went to [work for] General Motors, “The Man.” I never told anybody, none of my friends, because I thought I was a kind of revolutionary. I solemnly worked for GM for three years. This turned out to be very helpful when I went into business for myself, because potential clients were impressed by my resume: they didn’t see or care about anything else I did; they just saw that I had been at General Motors, so I must be okay. The work wasn’t creative at all. It was dictated by a very conservative mindset. All those years, I did interior design during the day, and then I’d go home and do my thing at night. And I never thought of [interior design and art] as being interchangeable until about fifteen or twenty years ago. Of course, it’s all part of what I do; I can’t unlearn something. [As an interior designer,] I was working with fabrics and making order out of space, color, and shapes. It’s all very much a part of who I am; it’s all very interesting and transferable.

LM: Rust has become a character in the narrative of Detroit. I’d like to hear about you working as artists within the city and the materiality of Detroit. Dabls, your installation has become a landmark of the city over the past few decades. Why do you think Detroit relates so strongly to your work? And Carole, rust is a material you seek out and embrace. How do you relate to that and also to the narrative of Detroit?

OD: Iron was the key to the industrial revolution [in the United States]; now you see iron exposed, in these vacant warehouses. But my use of iron had more to do with the African industrial revolution, and it’s connected when I’m doing my research. The automotive industry was not related to what I’m doing now, except [for the fact that] without its demise, iron wouldn’t be as readily available in the city. Now I seldom see a piece of iron lying around because people are scrapping it; it’s a business. I am amazed they haven’t zeroed in on this place and taken the iron I have out here. It baffles me: people are breaking into buildings for the iron pipes, and here iron is out in the open.

CH: Well, I am a born and bred Detroiter. I’ve been here my whole life, so I’ve seen it go through cycles; I love everything about it, and it’s not new to me. I feel differently about it than people who are writing about it [as a ruin]. We’ve been here all this time, doing the same things through all the years, and they just discovered it. It had been industrial, but the industrialists are the ones who left. This city is their throwaway, their discard. Dabls has thought of ways to make sculpture out of iron, and I make color out of iron.

Roundtable Discussion #2 premieres in June with Taylor Aldridge, Laura Mott, and the Detroit artists Matthew Angelo Harrison and Tiff Massey.