Editor’s note: In December 2020, Shantell Martin approached the author and editor to share a follow up to the project covered in this article. The artist’s full statement is reproduced below.

I offer here, three years following the publication of this article by Nettrice Gaskins, a few thoughts on the lessons I learned from this project, which ended up being an awful experience for me and an unhealthy collaboration.

As someone who has been collaborating for over twenty years, I’ve always enjoyed and respected the art of collaboration. It’s been a very organic process and something that gives me great enjoyment and has helped to strengthen my work. However, after this project, I will no longer walk into any collaboration without asking many questions first.

The most important lesson being, the fundamental action of establishing that all collaborators, essentially, come together with a goal to answer similar questions. The collaboration is a joint effort towards a similar goal. Getting to that goal requires that your creative moral standards are in alignment and that you share similar ideals when it comes to artist rights and ownership.

Unfortunately, when all was said and done, my collaborator on this project tried to use this project as an example for the rights of AI and move the needle further away from the Artist.

This is not only the antithesis of what I believe in as an artist but what I believe in as a human being. I write this now, to caution those who are curious to work in the realm of AI/Deep Learning.

These tools can be powerful, but we need to make sure that the intentions and purpose behind these tools always remain as a source of support vs a potential way in which artists and their work is further exploited.

—Shantell Martin, December 2020

“Who are the algorists?” Simply put an algorist is anyone who works with algorithms. Historically we have viewed algorists as mathematicians. But it also applies to artists who create art using algorithmic procedures that include their own algorithms.1

Developed from the study of pattern recognition in artificial intelligence, or AI, machine learning involves the creation of algorithmic neural networks that can learn from and make predictions about data. Examples of machine learning include self-driving cars and image and facial recognition programs. Computers can learn to draw visual forms if directed by instructions, usually given in the form of algorithms. Some artists use algorithmic procedures to make art through computer code or other information that determines the form the art will take. Mind the Machine, on view at Open Gallery in Boston’s Leather District, attempts to rehumanize the concept of algorithmic process and to uncover elements of an artist’s identity.

The current show presents work by Shantell Martin, a British visual artist currently based in New York, in collaboration with PhD candidate Sarah Schwettmann, studying computational cognitive neuroscience. Martin and Schwettmann trained a deep neural network to recognize recurrent elements of three hundred drawings by Martin and identify key elements of her artistic identity, enabling it to learn her artistic style. After the training, the deep network could predict how Martin would complete a given drawing.

Martin is best known for drawings and light projections based on her stream of consciousness. Feeling restricted by growing up in a working-class neighborhood, Martin looked to graffiti to express herself. As her work and life developed, she became more concerned about the personal meaning of her work, specifically addressing and analyzing what made it unique. Martin has been involved with several collaborations, including a seventy-five-minute performance with Kendrick Lamar at the 2016 Art Basel Miami Beach fair. For this collaboration, Lamar used a machine to create different beats; Martin responded to the sounds with drawings on a blank canvas. Mind the Machine invites visitors to further explore the structures underlying Martin’s artistic process.

We often get our narratives for understanding algorithms and machines from an entrenched technocracy. In Mind the Machine, Martin and Schwettmann invite us to explore the narrative of a disembodied artist and imagine what our world might look like were we to automate the creative process.2

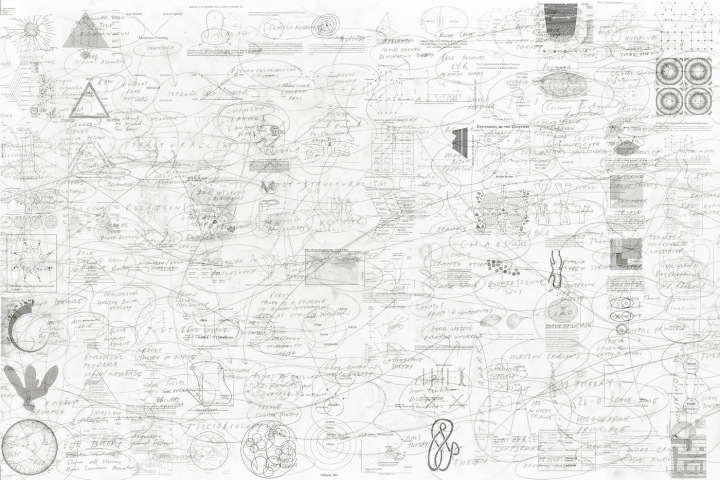

The Boston show includes sets of illustrations or templates that address Martin’s artistic identity and the space between an artist’s truth and a machine’s simulation. Mind the Machine expands on the idea of the “thought-object” explored in Matthew Ritchie’s recent work and merges it with procedural drawing and machine learning.3 Channing Hansen’s algorithmic hand-knit designs are based on his DNA.4 Shantell Martin’s drawings are diagrammatic, as they explore concepts and ideas through, as she states, “a meditation of lines; a language of characters, creatures, and messages that invite her viewers to share a role in her creative process.”5 According to Schwettmann, the consistency of Martin’s drawings indicated that aspects of her process were machine-learnable.

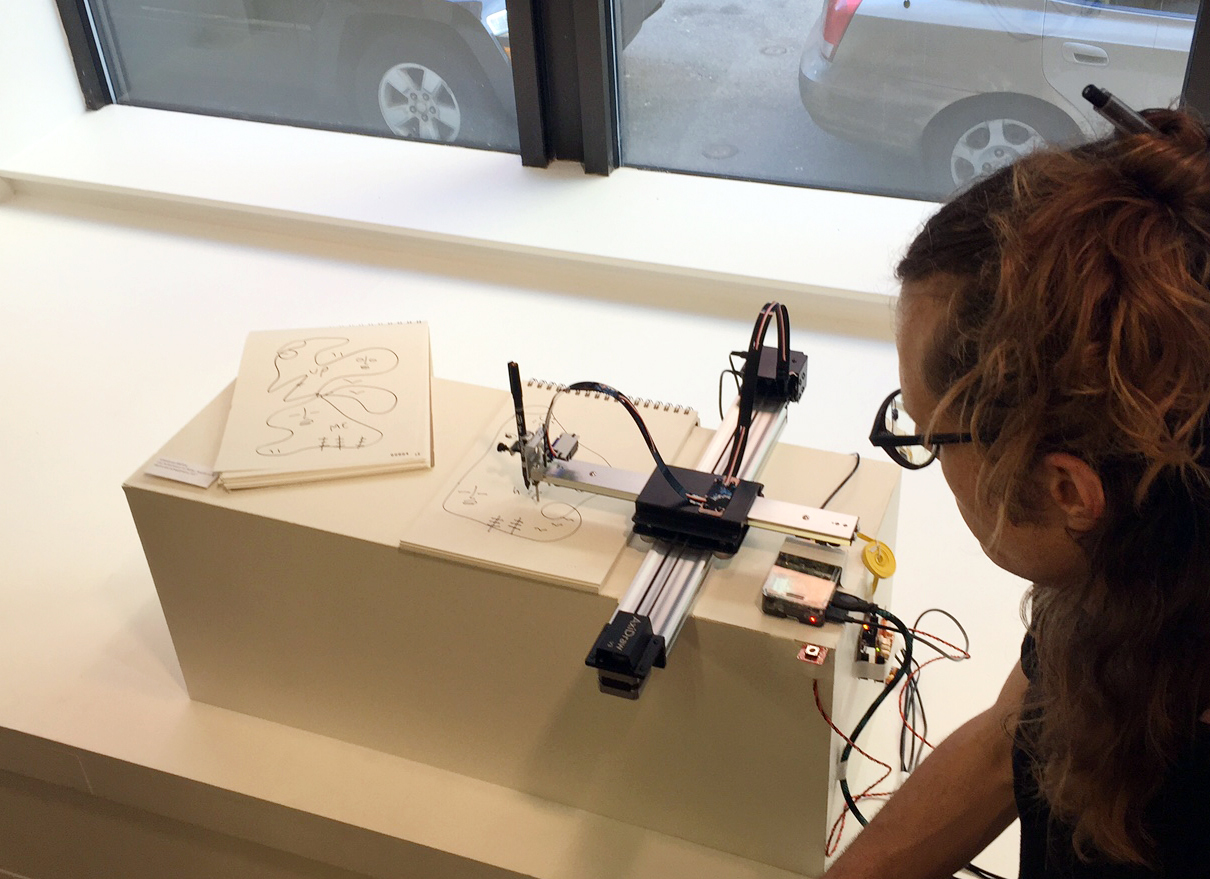

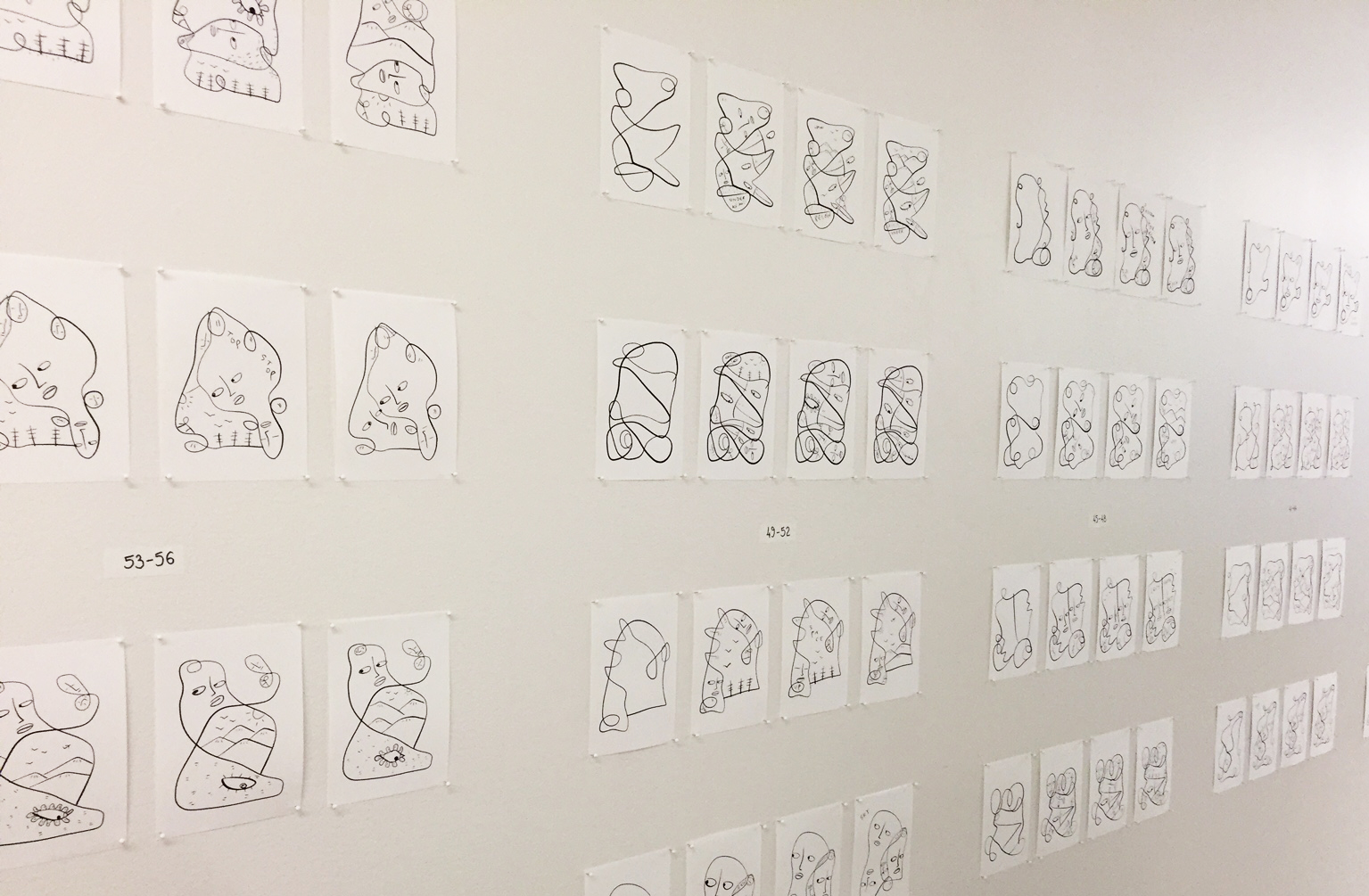

To produce images to train the algorithm, Schwettman sent Martin three different template illustrations every morning for one hundred days, to complete using iPad software that suits her approach to drawing. Schwettman’s AI software separated elements of Martin’s drawings, matching each contour to a predefined one. Then, the algorithm generated variations according to the parameters of the original templates; when this data was run through a robotic plotter, it produced automated illustrations. In this way, they created an algorithm capable of completing drawings in the same way the artist would in her original compositions.

In the gallery, Martin and Schwettmann installed a robotic plotter (driven by a Raspberry Pi, a small, single-board computer) that issues new drawings generated by this algorithm through the run of the exhibition. Also on display are Martin’s three hundred hand-completed templates that were used to train Schwettman’s AI system and a series she painted with acrylic on canvas.

[We are] drawing spontaneously and intuitively, and it is about trusting the pen and allowing the pen to unfold in the way it wants to; but the flip side of that is that we’ve also practiced and have a process…(S)ometimes, when I’m creating the drawings, I may have no idea what I’m doing, so you’ll see these little dashes. Those dashes are almost like when you’re talking and you say “um,” you know? They’re these moments when you fill that space, but that’s also a part of the work itself.6

Rather than presenting the algorithmic process and development as a replacement for human-produced art, this collaboration offers a window onto markers of identity that could further the potential of art as a tool for self-expression, heightening awareness of one’s artistic process and refining an artist’s style.

Mind the Machine is on view through July 21, 2017.

1. Roman Verostko, “The Algorists.”

2. “Mind the Machine, Shantell Martin and Sarah Schwettmann,” Open Gallery.

3. Ritchie’s The Temptation of the Diagram, on view at ESMoA in El Segundo, California, maps the history of human diagrams.

4. Hansen’s solo show is at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London through July 29, 2017.

5. “Shantell Martin on Finding Self in Drawing,” from a conversation with Brandon Stosuy, October 25, 2016, The Creative Independent.

6. Ibid.