Our latest New York Close Up release, “Caroline Woolard’s Floating Possibility,” was epic in many ways. Epic in time frame: We started shooting in the spring of 2016 and wrapped up editing in July 2017. Epic in locations: UrbanGlass in Brooklyn, various beaches in the Rockaways and Jamaica Bay, and the Knockdown Center in Maspeth, Queens. Epic in scope: The film focuses on artist Caroline Woolard and her collaborators’ still unfolding project Carried on Both Sides, an ambitious program of video, sculptural works, lecture, and a website. The process behind the film was epically educational for me as a producer and director—particularly working with an underwater camera in the swelling Atlantic water. So I thought I’d take the opportunity to look back and share what I learned for those about to brave an underwater shoot.

1. Hire someone experienced. And with gear. Good gear.

The heart of Caroline’s Carried on Both Sides project is the glass amphorae she created with artist-collaborators Helen Lee, Alexander Rosenberg, and Lika Volkova. What really inspired me to do a film around the project was the prospect of shooting their experimentation with the vessels at New York City beaches. Though I have shot underwater before (see “Alejandro Almanza Pereda Escapes New York”) that was more of the GoPro-on-a-stick-in-an-aquarium variety of photography. Inspired by Caroline’s own formal ambitions, I knew I needed to up the ante.

After posting for a underwater cinematographer on the always helpful Video Consortium Facebook Group (an excellent resource for finding crew and gear anywhere in the world), I hooked up with Tyler Haft. A recent transplant to Brooklyn from California and a long time surfer turned surf photographer who grew up in Manhattan Beach, Tyler definitely had the right bio—and the right gear: A Sony Fs7 with custom-built underwater housing. Most importantly, Tyler’s also capable of sheer surfing video bliss like this:

Tyler also shot the skateboard footage in another New York Close Up film, “David Brooks Hits the Pavement,” while on a skateboard himself. Apparently balancing on a skateboard and surfboard while shooting with expensive cameras are completely transferable skills.

Sony FS7 Water Housing. Photo courtesy of SPL WaterHousings.

2. Reconnaissance can be helpful. But luck is even better.

Now that I have my cinematographer, the next step is the where. After a number of failed attempts to meet up with Caroline at possible Rockaway beach spots, I went against my usually careful nature and decided not to scout shoot locations ahead of time. Fast forward to the shoot day. A beautiful Sunday in late September, and the excited crew—Caroline, Tyler, Alexander, Lika, and Caroline’s studio assistant Samantha Rosner—arrives at our first possible location.

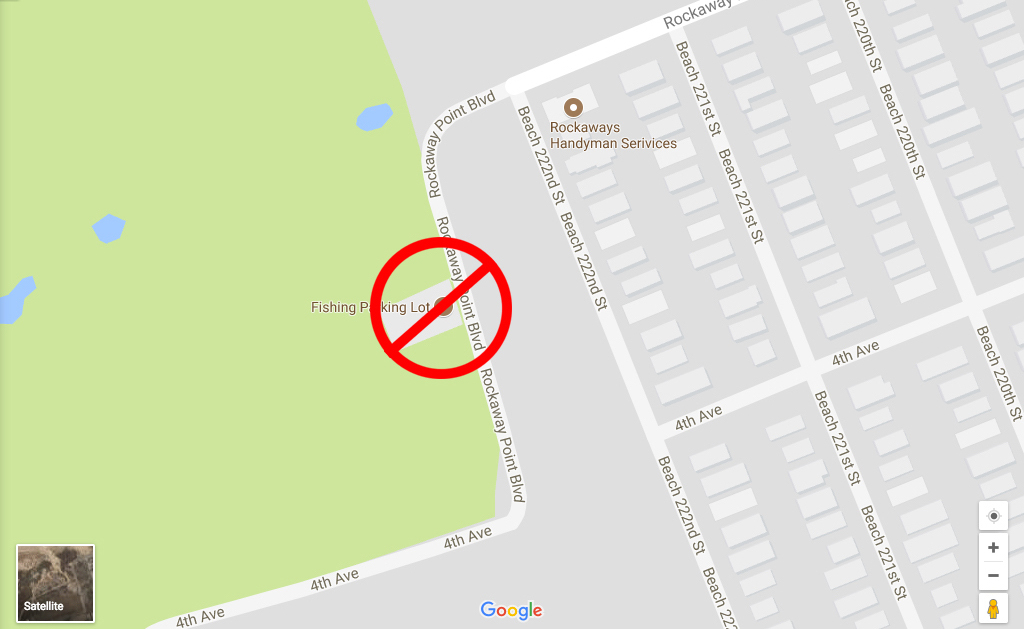

Caroline, the conceptualist artist and perennial risk taker, was cool with parking at a fishing permit-only lot in the far western reaches of the Breezy Point neighborhood. Me? Not so much. (I actually looked into getting a fishing-parking permit earlier in the week; it would have required me showing up at the National Park Service’s admin office with fishing poles, a ruse I wasn’t willing to take that far.)

But luck, in the form of a couple of good samaritans, was on our side. A father and son packing up their gear saw our confusion and suggested a nearby permit-free beach: Floyd Bennett Field. (And if you haven’t visited Floyd Bennett Field, do so. It’s a very cool mix of aviation history, beach and woods, and gatherings of random hobbyists like drone fliers and archers.) The father and son actually lead us there, us driving right behind them, and we wound up at the perfect spot on the far eastern side of the park. No permitting signs. Few people. A long shallow beach and gentle, glass-friendly swells. I don’t know your name but whoever you are, kind Jamaica Bay fisherman and son, thank you!

WPA poster, 1937. Promoting New York’s municipal airports, Floyd Bennett Field and North Beach. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

3. Don’t drown your cinematographer

After getting our bearings, Tyler built out his gear, put on an old wetsuit, and we were good to start the shoot.

The first half of the day was most pleasant, at least for me. We waded out into waist-high water, shooting the vessels from both above and below the surface as they hypnotically bobbed in the bay. We learned how Caroline & Co.’s delicate glass amphorae behaved in the water, and in general enjoyed the odd experience of being half-submerged in Queens in late September, with the Manhattan skyline visible behind us. The only bummers being the occasional brush with a phantom crab, and how damn big 4K video files get (but more on that later).

The second half of the day was a bit different, at least for Tyler. Looking for a bigger swell, we moved to another Rockaway beach where Tyler had a lot to contend with. Not only did he have to negotiate the subtleties of finding focus with a fixed lens trapped in what’s basically a floating box, but he also had to battle much rougher surf. Lying flat on his stomach, right at the edge of the shoreline with his director (i.e. me) hovering above him, Tyler was clearly in distress trying to get the perfect shot of the waves rolling over an amphora. But his stoic inner surfer—or better yet Navy Seal—prevailed, and we got some AMAZING footage.

Helicopter Shark, hoax photo from 2001.

It turns out that near drowning in shallow water was nothing for Tyler. He later regaled me with stories of much worse. Apparently he did a San Francisco Bay job where he was floating in open water, literally under the Golden Gate Bridge where great whites had recently been spotted. And understandably, he seriously freaked out.

4. Pack a lunch

Despite its growing reputation as a foodie destination, Rockaway, or at least the parts where we shot, did not have easy access to food. And I didn’t think Seamless would be able to service the little nook of Floyd Bennett we stationed ourselves in. Fortunately though, we were thinking ahead, or more accurately Caroline was. She brought an assortment of vegetarian and non-vegetarian sandwiches from the legendary Park Slope Food Coop, and I brought my usual assortment of high fat, high protein snacks. I highly recommend dark chocolate covered cashews for those inevitable energy lulls.

5. 8-bit color is not cool—bring extra storage

Remember when I complained about video file sizes? Well, our response to not having enough camera card space for a full day of shooting was to shoot in a more compressed file format. That codec was in an 8-bit color depth. In hindsight, not our best idea. The smarter option would have been to fully charge my laptop so I could have transferred the video files to drive storage in the field as we filled up our camera cards. Alas that wasn’t the route I took.

As is well documented all over the internet, 8-bit color along with other variables including the in-camera LUT can produce images like this, something usually referred to as “color banding”:

Yikes! Look at the sky in particular. Instead of appearing as a uniform gradient of blues, there’s very unnatural, digitalish stratas of distinct blue tones. Ugly! Sad! Banding! And the worst part is that this banding is typically not visible on the camera monitor in the field (so you don’t even know it’s happening while you shoot) and it tends to be exacerbated when the footage is later color corrected, scaled up, or exported to more compressed codecs like h264—our codec for posting finished films on Vimeo. So I, of course, only discovered this issue after bringing the footage back to the office.

Having gone out of my way to make this film as pretty as possible, I knew this banding issue had to be combated. Fortunately there are solutions. And more fortunately, I had hired just the right editor to figure them out: Anita Hei-Man Yu. Fast forward to June in the edit room, and after some internet digging and her own testing, Anita came up with this not-too-complicated workflow: Bring the footage into an 32-bit color composition in After Effects, add one percent video noise and a little bur, open the project in Premiere Pro, and color correct from there. Voila!

SO much better.

6. Enjoy your job

One of the distinct pleasures of my job is the constant thrill of doing something odd and fun and memorable that I’d never do otherwise—something only justifiable by calling it art. And I’d only be standing waist-deep in Jamaica Bay, corralling a group of unruly glass amphorae in the name of art. So when I do have a shoot with a more relaxed schedule and a less ambitious shot list, I actually try and relax—enjoy the moment and the community of folks that come together to create a little cinematic beauty. After all, it’s just a movie.