Maya Lin. Folding the Columbia, 2017. Glass marbles and adhesive; 13′ x 26′ x 1″ (396.2 cm x 792.5 cm x 2.5 cm). No. 67693. © Maya Lin Studio. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

Today, Pace Gallery is opening a new exhibition of work by Maya Lin. Titled Ebb and Flow, the show features eleven new installations and sculptures—all of which explore that ever-precious, ever-powerful natural element, water. “I’ve always been fixated on water,” Lin writes in the gallery’s press release. “Maybe it’s because it exists in multiple states, and you can never understand it in nature as a fixed moment in time.” I spoke with Lin by phone to learn more about how she sees her work functioning in a time of record rainfalls and back-to-back hurricanes.

This is the first of a two-part interview with Lin. The second interview focused on the artist’s What is Missing Foundation, a project she describes as her “last memorial.”

Lindsey Davis: Your work often references an imbalance in the ecosystem that’s caused by humans, yet the exhibition’s title implies a kind of natural balance that persists nonetheless. In your work, how do you square the balance and harmony of the natural world and the extent to which humans disrupt that balance?

Maya Lin: In a normal situation without climate change, the climate is [still] always changing in a way. One could argue that the sea level has always come and gone, and I think what we’ve got right now is this insane inflection point with climate change. If anything, what you refer to as a harmony of the natural world [and our disruption of it] are partnered and paired, and there’s a little bit of an irony in that what normally might take millennia is happening within a hundred years. People just don’t realize how rapidly the seas are rising. People don’t realize how rapidly species are going extinct, and we’ve just magnified that.

So it’s not like there’s one which is in stasis, because the planet is perpetually moving in a weird way. One could call that “slow time” (the planet’s cyclical ecosystem without human impact), and Ebb and Flow plays off of that slow time. One could also reflect on—especially with the middle room of the show with the Arctic and the Antarctic and the pull where they really become bellwethers—[the fact] that we’ve just sped it up immensely.

Oddly I think, like a lot of my work, there’s something ambivalent about it—I’m drawn to things that have a slight ambivalence, or they’re of two minds, and so this ebb and flow seems so natural right? And yet it can also refer very much to what is happening now, which is not at all the natural stability, so to speak.

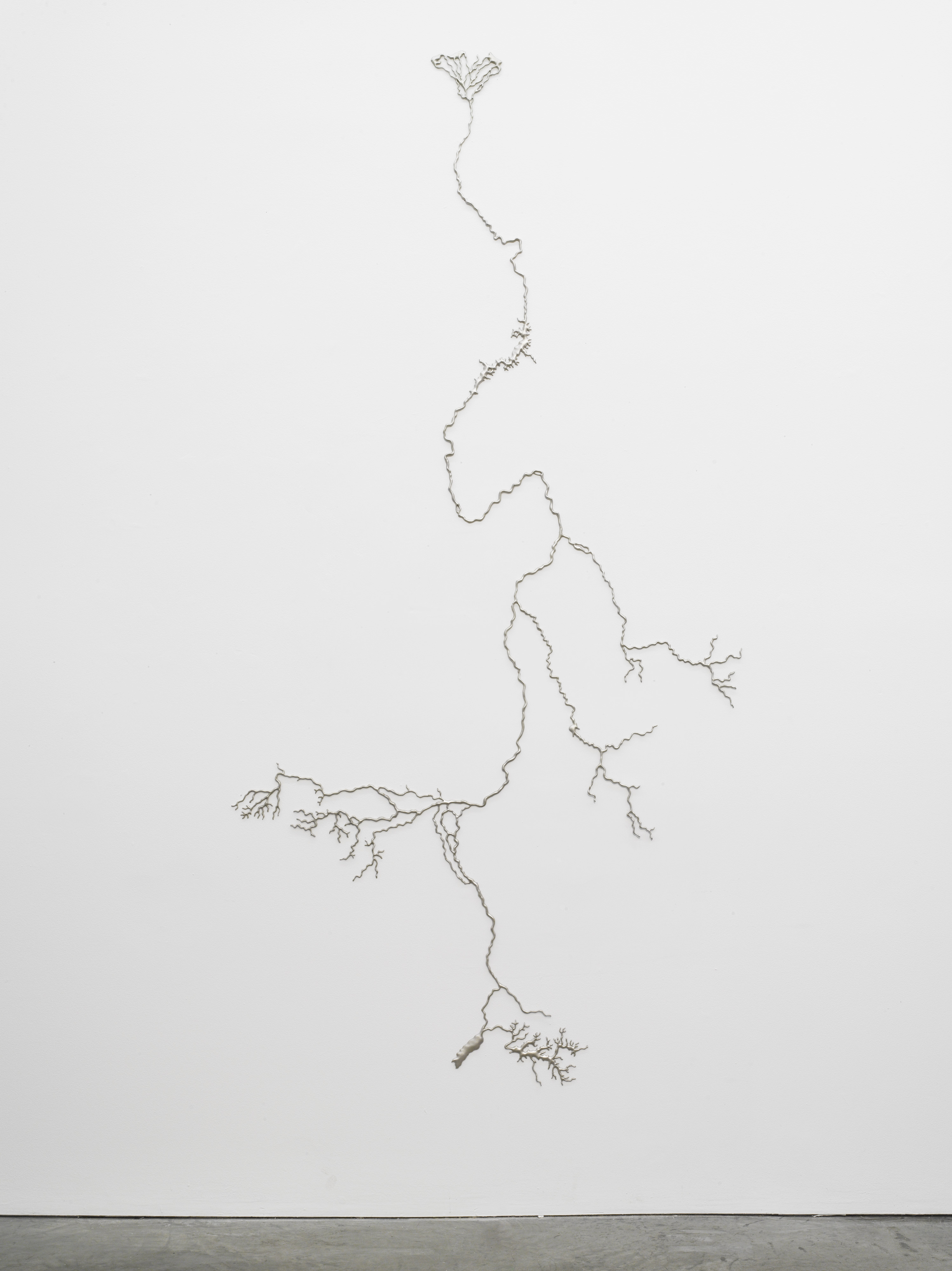

Maya Lin. Silver Nile, 2017. Recycled silver; 8′ x 47-1/8″ x 3/16″ (243.8 cm x 119.7 cm x 0.5 cm) No. 66846. © Maya Lin Studio. Photograph by Kerry Ryan McFate. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

LD: The small scale of your works lends a sort of delicateness to the natural element of water. How would you respond to someone in Texas right now after Hurricane Harvey, who’s experienced rising water as anything but delicate?

ML: Maybe it’s my personality, but I tend to be just the facts. Even if you look at the floodplain of Hurricane Sandy, I just distill that without emotion, without editorializing, without drama. I love scientific facts, because for me those facts are incredibly dramatic but they don’t ever appear so.

LD: You sort of remove the human element almost?

ML: I remove the drama. And I don’t know why. You know some people say, “It’s too subtle, it’s too pretty in a way, why is it so pretty?” Water, no matter what you do is unbelievably powerful and unbelievably beautiful. I am trying to deliberately strip it of its emotion, and yet allow the facts of the place, the facts of the form [speak for themselves.] In a funny way these are also all drawings. They’re mappings that I’ve chosen. Rather than make an abstract mark on the wall, I looked all over the planet and I see these beautiful drawings in them.

LD: What first inspired you to transform raw data into these drawings?

ML: I wanted to be a scientist when I was a kid. And yet at the same time, I find nature and science unbelievably hypnotic. I like to take walks around the world in an atlas, and find inspiration in those forms.

LD: Do you consider the pieces that result from those “walks” journalistic in any sense?

ML: Slightly. But in the end, they’re drawings.

LD: Drawings that the world made, and in a way, you’re translating them.

ML: Pretty much, and how I translate them becomes very different. I think that’s the key because there’s a very fine line that I tread between what makes it art versus [what makes it science]. I’ve been beginning to map not just the form itself, but the types of changes that are occurring, so that we can capture in time, what is transpiring. These are all moments in time that I’ve chosen to catch, they’re all forms that have been severely altered by us.

Installation view of Maya Lin: Ebb and Flow. 537 West 24th Street, New York, September 8–October 7, 2017. Photography by Kerry Ryan McFate. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

Things are shifting quickly, so the title of the show Ebb and Flow, it’s all about everything that is in flux in nature and maybe trying to capture a moment. One [piece] that I love is The Rivers Run North, which is a pin river of all the waterways that flow into the North Pole. One of those rivers just reversed course because of the way the Arctic is melting. The middle room [of the show] is all about the North and the South Poles, the disappearance of the Arctic ice caps and the Antarctic, which we just don’t think of. One explorer referred to the Arctic ice when he first saw it as “the curdled sea,” so there’s a couple pieces that are a new materiality for me. I’m working with encaustic and creating these encaustic, paper reliefs of both the Arctic and the Antarctic.

Another one of the pieces, Lake Victoria, is cut into the wall. As a sculptor, I have a dichotomy between my very large outdoor earthworks and the mapping I explore when I come inside. Yet at the same time, can I make the architectural space of a wall my earth? So Lake Victoria’s doing something that I’ve been wanting to do for quite some time, which is to cut away the wall and create a crater within it, yet it will feel like the wall has been sculpted.

In some of the smaller scaled works I’m also trying to play with coopting the space of a gallery to create these environmental pieces. Folding the Columbia goes from ceiling, wall, floor, out the small room it’s in and pours out and back up. Playing with an idea of what water can do and what it can’t do, making water flow upside-down and floating it up the wall—it just begins to take over a space, which is what water will do. It will go wherever it’s invited in, albeit with gravity, normally, in mind.

LD: How do you hope viewers will think of water differently after seeing the works in Ebb and Flow?

ML: Especially with the Poles, I hope that they will begin to think about these areas that are so remote and so abstract. I’m hoping they’ll look at these spaces and be able to think of the terrain underneath the ocean. Maybe it’ll pique your curiosity, maybe it won’t. We all know about these far off places, but how many of us will go visit them? And how many might just decide, “Oh wow I never thought about the Arctic that way.” Or the fact that we’ve lost almost fifty percent of the North Pole ice caps. In the Antarctic, the ice shelves that are calving are the size of the UK—it’s a vast expanse. If you think about what a map does, it gets our mind to analyze it and understand it and comprehend it, because these are vast areas that we’re dealing with. I’m a little bit of a cartographer in this show.

Maya Lin: Ebb and Flow is on view at Pace Gallery in New York September 8 – October 7, 2017.