Lumin, a mobile tour at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), supported by the Knight Foundation. Courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

In this interview, I talk with Chris Barr, the director of the Technology Innovation program at the Knight Foundation, about a new initiative: a collaboration between its arts and technology teams.

Nettrice Gaskins: How did the Knight Foundation come to support art museums through this collaboration of two of its programs, Arts and Technology Innovation?

Chris Barr: Beginning with the Journalism program, the foundation focused on technology, innovation, and the digital transformation of organizations that inform people online. My program, Technology Innovation, grew out of that work, in order to look at other fields and areas that are affected by information technology, such as libraries, government agencies, and now museums. In collaboration with our Arts program, we’ve been focused on how museums can better connect with visitors both inside and outside the museum buildings and how they can use technology to advance research in new ways. We seeded some experiments in that area through twelve grants this year, and we expect to provide more next year.

NG: What kinds of programs is the Knight Foundation looking to support in the coming year? What kinds of issues are you hoping to address?

CB: We will be funding more early-stage projects, such as prototypes and new ideas to connect people with art. We’re specifically interested in museum spaces and looking at technology that has the potential to scale up and be shared with other institutions, as well as programs that have novel approaches to using interactivity and online participation. We’ll also begin to look at how to build talent in the field. Technology is a new arena for many museums and cultural institutions, and we are looking at how we can attract people with technological expertise into these institutions to level the playing field.

Art Stories in Mia galleries. Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

NG: How important is technology, i.e. the internet in this new initiative?

CB: It’s not the most important thing, but I believe that participation is one of the key distinctions about new media. Aside from the earlier top-down models of knowledge transmission, we now have the opportunity to swap teacher and learner roles and to work directly with communities in new ways. The internet provides lots of options to do that. Many organizations may go through a change in their institutional culture in order to feel comfortable in these online spaces, where there is a different kind of participation and expectation from the audience.

NG: Many traditional museums use didactic information to orient museum visitors to a topic or theme. What are some ways that this newer technology can engage visitors in deeper ways?

CB: We’re looking at how technology, and the changes it brings to the culture, gives us new ways to think about or augment what we do. We’re asking, in addition to having those traditional didactic texts, where are the opportunities to make new connections with audiences? We’re asking museums to do a lot, to potentially go over and above what they’ve been doing in the past, in order to move into these new areas.

NG: Can you explain what NEW INC is about, particularly the incubator model, and how you see the tech industry working with museums? And how is the Knight Foundation a bridge for this work?

CB: NEW INC has an interesting approach based on the incubator model from the business-startup-investment field. NEW INC is focused on creative enterprises and has launched successful companies and design studios, as well as housed entrepreneurial artist projects. We’ve sponsored them to do museum technology tracks through their incubator, to bring in folks who are interested in working within the museum context. Our hope is that this will build turn-key products for museums and build creative studios that understand the needs and constraints of museums, to better serve them with boutique solutions. The program also invites museums to tech demonstrations at NEW INC, and there the companies can also learn from the museums. We really believe that this sharing—between technology startups and museums—can help to build mutual appreciation that will lead to better solutions for museums.

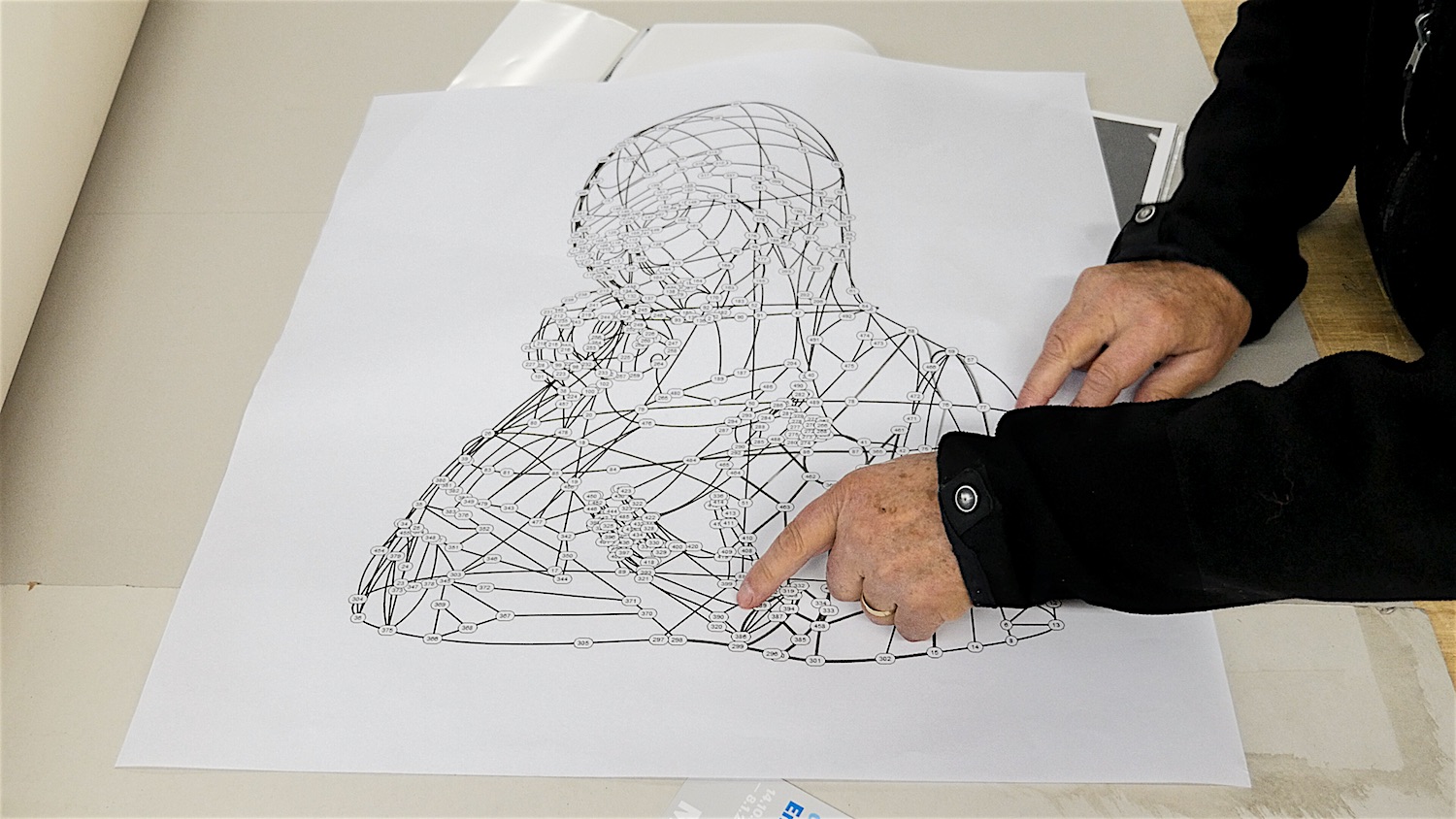

A digital rendering for Thomas Bayrle’s Wire Madonna (2016) at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. Courtesy of ICA, Miami.

NG: Could you talk further about the prototyping component of the program—specifically, what a prototype is and how you see prototyping being used in museums?

CB: When we look at prototypes, we ask: What is the least you need to build in order to test an idea? What can you make that helps to test the feasibility and desirability of a given solution? How can we test individual components and quickly iterate as we move along? Unlike approaches in which people lay out a plan and build a product over a long period of time, we’re focused on getting products in front of people at earlier stages so that we can assess if we’re on the right track. This is the predominant model in the software industry. We’re accustomed to seeing beta tags on software that we use online; the approach is “release early, release often.” Museums will traditionally work on an exhibition for a number of years, and the public won’t see anything until the perfect final product. For museums, this new program will be challenging: to put something in front of the public that might not feel finished in order to come to a better product; to continually improve rather than just make one final public version. This is the culture shift I mentioned. Most museums and other legacy institutions are not used to this rhythm; going through [the prototyping process] a couple of times helps.

NG: There’s a lot of excitement about augmented reality, especially with the announcement of the iPhone X. This type of rapid change in technology can be daunting even for museums with in-house technological expertise. What are your thoughts on this?

CB: Prototyping is not limited to the technology field. A Knight Foundation grantee in Akron, Ohio, is prototyping service models rather than a piece of technology: setting up booths and physical kiosks to see how people react to them and to [subsequent] changes. Maybe there’s an opportunity to think about a portfolio of technology solutions: the major infrastructure, the things built from that infrastructure, the small experiments—ones that allow you to see what delights people in new ways—that join the portfolio when they become successful. Our mindset is that one should always be trying things. Alone, the word innovation is daunting. Most people don’t identify themselves as innovators, but we need more people innovating, more often. Innovation can come from anywhere, and we do the field a disservice when we say only certain people are innovators and don’t empower more people to be part of that process. Part of the model that we use at the Knight Foundation’s Prototype Fund, through human-centered design and other methods, is looking at how we can empower more people to be part of creating the next version of the museum, of the library, and of our government.

Mark Smith Planetarium at the Museum of Arts and Sciences. Courtesy of the Macon Museum of Arts and Sciences.

NG: How can people inside and outside of museums be more involved in the museum and technology initiative? What opportunities can people expect in the future?

CB: We take every opportunity we can to share knowledge that comes out of these projects. Part of the reason we support early-stage projects is because even if the project fails, there is valuable learning that can be shared with the field. We can say what happened, why it didn’t work, and what people should think about when doing similar projects. In addition, although not every museum is ready to adopt a new piece of technology, we can build a community of practice and encourage an attitude shift toward technology. When utilized to advance our missions, technology can be a valuable tool. So how do we use this tool to advance museums’ missions? There are lightweight technology solutions, like social-media tools, and there are more robust ones. As a community-based foundation that has focused largely on need-specific cities, we know that most museums are not like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. How do we help the whole field rise to the same level? The solutions will come from increasing conversations between the museum and technology sectors.