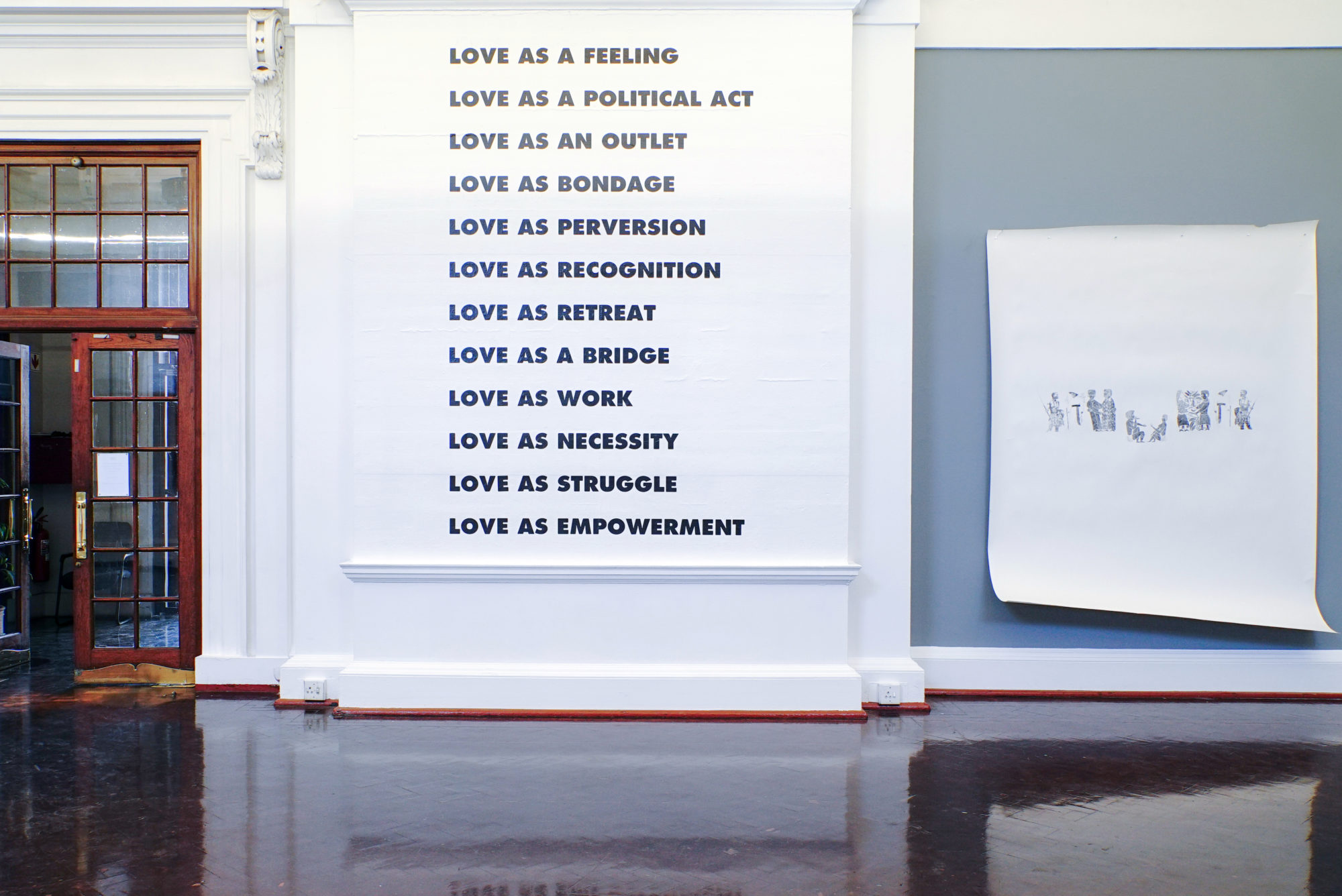

Installation views of the exhibition A LABOUR OF LOVE at Johannesburg Art Gallery, curated by Yvette Mutumba and Gabi Ngcobo. Photo: C&.

“We don’t live in an age of reason, we live in an age of empathy,” states the Dutch psychologist, primatologist, and ethologist Frans de Waal.1 In a time of still growing poverty, more frequent natural disasters, increasing threats of terrorism, ongoing wars, and rising right-wing populism, one might wonder how this can be true. A common notion of empathy is the capacity for understanding and sharing of others’ feelings by imagining oneself in their positions—and, by extension, feeling caring, love, and goodness for them. So, if we live in an age of empathy, as de Waal puts it, why does the broader world seem to be such a mess? In his book Against Empathy, the psychologist Paul Bloom argues that the force of empathy powerfully shapes our moral decisions and actions. However, according to Bloom, this makes the world even worse. Why? Because empathy is biased. Empathy for individuals close to us can even be fatal, in that it might result in problematic behavior toward others—possibly culminating in racism, violence, and war. While Bloom has a point, I regard empathy not only as a capacity for doing good but also as a possible strategy to unite different and complex histories, cultures, or political views. Empathy is human solidarity. Various psychologists and ethologists have argued that empathy is learnable. I believe that one way to learn empathy is through the production as well as the consumption of creative expressions in literature, film, dance, and visual arts.

As an art historian, editor, and curator, I consciously regard empathy as a methodology to approach projects and processes. Empathy can be an important instrument to acknowledge the existence of the most varied narratives, emotions, and experiences of creators as well as audiences. Empathy can be a tool for curating exhibitions, writing texts, and editing magazines that not only offer answers but also raise questions. The result is a continuous flow between remediation, research, emotional response, and positioning oneself within a broader discourse and practice. Here, the subjective contemplation of complex topics and the consideration of other perspectives are equally important. Empathy can therefore be a compass to help one navigate through the abundance of cultures, contexts, resources, and timelines. It is an option to contribute to a contemporary society, one that can create spaces for diverse voices—that can lead to greater perception and understanding of issues troubling the world today. However it should also be a tool for sharing stories that are inspiring and promising.

1. Paul Bloom, Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion (Bodley Head, 2017), 6.