The filmmaker’s mother. Production still from Jumana Manna’s A Magical Substance Flows into Me, 2015. Co-commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation and Chisenhale Gallery with Malmö Konsthall and the Biennale of Sydney. Courtesy of the artist and CRG Gallery, New York.

Since watching A Magical Substance Flows Into Me, I’ve been craving pickles. In the film’s first sequence, there is a bloody close-up of a huge jar of red pickled turnips in a kitchen window. It’s an extraordinary shot, and the camera lingers generously. This camera enters many kitchens: the filmmaker, Jumana Manna, interviews her subjects in their homes and workspaces all over Palestine and Israel,1 and she asks them to play music. Inevitably, the kitchen becomes a destination for conversation and sometimes song. One woman sings as she steams dumplings on the stove, and her band-mate plays a mandolin.

A Magical Substance is filled with expressive close-ups of objects, as well as wider shots of the people who make and use them. This film might be viewed as only about such potent minutiae: the textures of musical instruments, pickles, paper. But they are contextualized within a violent conflict that has a long history—a friction that we see in the images of tall concrete border walls. Intermittently throughout the film, Manna’s father provides historical context from a book he is writing. Other than Manna and her family, all of the films’ subjects have something in common: they are descendants of people whose music was recorded by Robert Lachmann, a German scholar of Middle Eastern music. Lachmann, who immigrated to Palestine after the Nazis rose to power, was controversial for a 1937 project that included music from many ethnic groups in Palestine, including Jewish and Muslim people. He becomes a character in the film, as Manna plays his recordings and reads from his writings.

Liron Amram & Aharon Amram. Production still from Jumana Manna’s A Magical Substance Flows into Me, 2015. Co-commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation and Chisenhale Gallery with Malmö Konsthall and the Biennale of Sydney. Courtesy of the artist and CRG Gallery, New York.

Moving from home to home, the film shows that an answer or an antidote to violence might be found in the sharing of music, food, and intimate spaces. The warmth of this kind of communion leads to affection and compassion. I feel it myself, craving at once the subjects’ food and their stories. Frantz Fanon writes, “I want the world to recognize with me the open door of every consciousness,” and the film suggests that communion in the kitchen might yield this recognition. I do wonder, really, how it could be possible to see someone’s home like this and still wish them violence. At the same time, I continue to wonder why so many of us remain ignorant of the “open door” Fanon proclaims, when it should be self-evident. (I detect this confounding ignorance both within and outside myself.)

Beyond its subtle invitation toward basic empathy, the film quietly illustrates the shared cultural history between different groups from this region. This history is audible in shared musical scales and visible in the teardrop bodies of some stringed instruments. In Israel, Muslim Arabs and Israeli Jews have been painted as opposing cultures, but in recording the music of different people in the region, the film illustrates a more complex reality. A singer named Neta Elkayam—the woman steaming dumplings—talks about the Israeli state’s attempt to “flatten” aspects of her multi-faceted identity: “Moroccan Jewish culture… our Arab-hood.”

Liron Amram & Aharon Amram. Production still from Jumana Manna’s A Magical Substance Flows into Me, 2015. Co-commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation and Chisenhale Gallery with Malmö Konsthall and the Biennale of Sydney. Courtesy of the artist and CRG Gallery, New York.

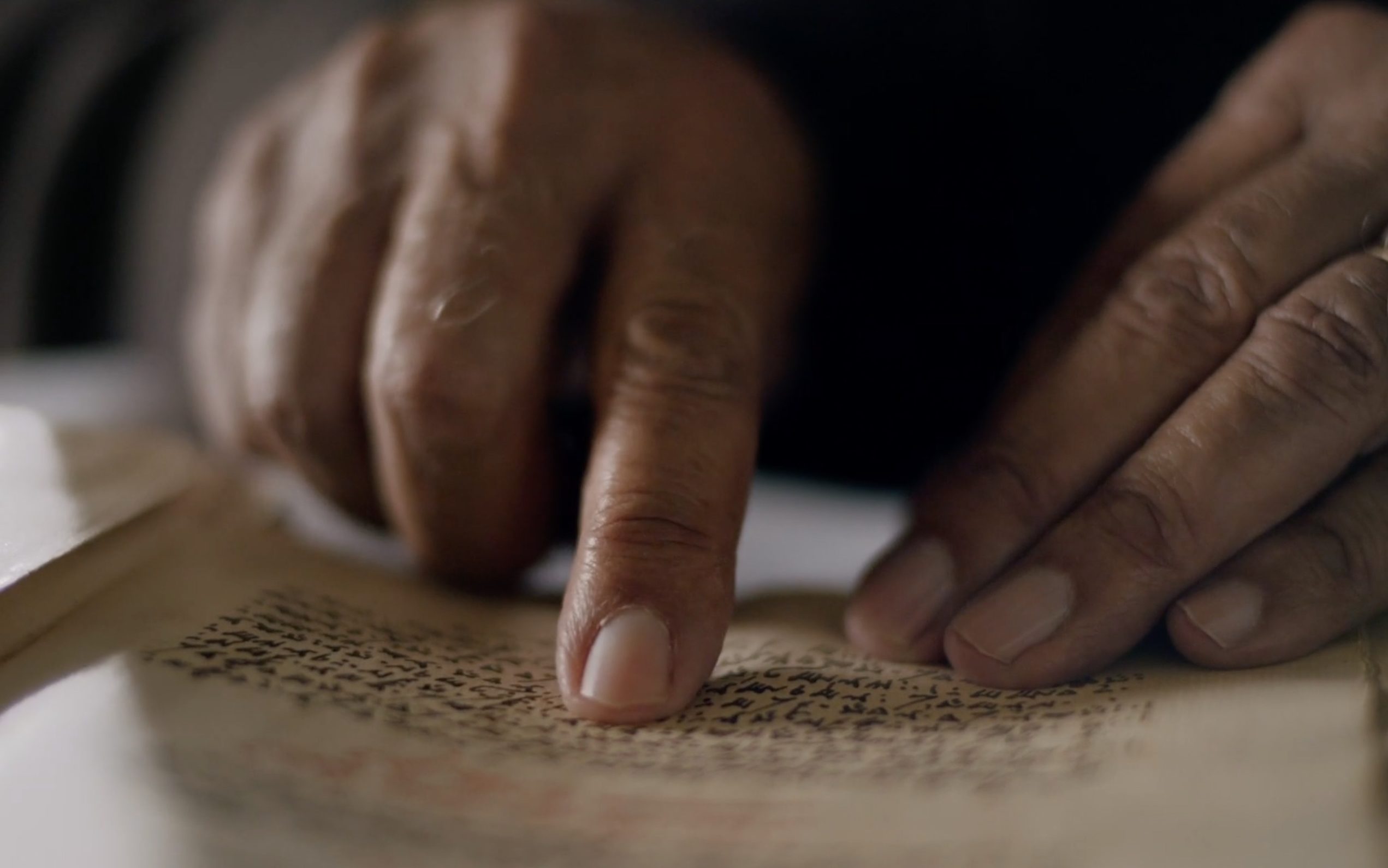

While watching the film, I find myself searching for clues to my own composite background; I have ancestors of various races and ethnicities, but the largest group is Jewish. Strangers sometimes detect Jewish features in my face, but sometimes they see less familiar origins: sometimes Egypt, sometimes Brazil. When I watch a group of people in the film whose cultural practices seem to have survived history’s blows, I am moved. (From Wikipedia, I learn that there are fewer than eight hundred Samaritans in the world.) These people, the Samaritans, read a leathern Torah and worship before a deep-turquoise tapestry with gold Hebrew lettering. At first, I mistake these as Jewish practices done with ancient Jewish objects, and I feel something. To learn, instead, that there is more than one surviving Hebrew religion does not dampen or undo this emotion. I still have little knowledge of these people, but I spend enough time on Google to learn that, like me, the Samaritans can be recognized as Israeli citizens if they serve in the military. Like me, however, they would have to undergo conversion to be recognized as religiously Jewish.

In a quiet way, A Magical Substance undermines the state-sanctioned forgetting of complex cultural contexts. It shows how this myopia has spurred hate and how immanent hatred is a falsely constructed identity. My understanding of this film, however, came only after viewing it several times. Manna’s film reminds me of Rebecca Walker’s words about how to attend to the identities of others: “You show your natural curiosity and talk to people and ask them how they’re living and what they’re doing and try to connect on a level that’s not based on their configuration.” Walker says that transformation it is a long and arduous process. I like to think this burden should belong to colonizers, those empowered by the state. As a Palestinian woman, however, Manna is part of a colonized population. She is also the only person who could have made this film.

Samaritan scripture. Production still from Jumana Manna’s A Magical Substance Flows into Me, 2015. Co-commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation and Chisenhale Gallery with Malmö Konsthall and the Biennale of Sydney. Courtesy of the artist and CRG Gallery, New York.

1. The state of Palestine that occupies the West Bank and Gaza Strip is recognized by 136 members of the United Nations. It is not recognized by the United States, and it is not labeled on Google Maps. Israel has occupied these territories for fifty years. This occupation has compromised Palestinian human rights according to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.