Orawan Arunrak. Exit – Entrance, 2017. Installation with wallpaper with printed drawings, 10 sheets of handwritten text, QR code, light, curtain, 2 floor cushions, sound (65 minutes, co-editor: Pedro Ferreira). Dimensions variable. Installation view, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin. Photograph by Wolfgang Bellwinkel. Courtesy of the artist. © Orawan Arunrak.

When I ask Orawan Arunrak what she thinks about the word empathy, she answers in a typically cryptic manner. In the Thai language, the artist explains, it may translate roughly as “to take your heart when you [are] working on something.” For Arunrak, to work without empathy is unthinkable. Her practice, which is based on loosely choreographed interactions between the artist, various interlocutors, and the spaces and places that they share, is empathetic in motivation and method. Yet it also makes visible and audible the manifold conditions that limit possibilities for mutual understanding.

When I most recently visited her Berlin studio, long strips of paper inscribed with lines of text written in English, German, Thai, and Vietnamese lay tangled together in a mass on the floor. The placement and curling enmeshment of these writing-drawings rendered them impossible to read (and it is rare to find an individual who is fluent in all four languages, in any case). The arrangement—a sketch, or work-in-progress—was tantalizing and suggested possibilities for communication while pointing to their closure.

Orawan Arunrak. Exit – Entrance, 2017. Detail of wallpaper with printed drawings. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. © Orawan Arunrak.

Arunrak is keenly interested in language. She says, “My work is a word,” a kind of “language to communicate with myself, people, the world.” Self, people, world: in her slow and quiet practice, these categories converge, coming in and out of focus only in relation to one another.

In her most recent solo exhibition, held at Berlin’s Künstlerhaus Bethanien in 2017, recorded voices in English, German, Thai, and Vietnamese were interwoven and overlapped, a sonic equivalent to the strips of paper I saw on her studio floor—indeed, the sound installation grew out of those experiments. The piece created an occasionally incoherent and often mesmerizing environment that, like the paper strips, both proposed and frustrated communication. An earlier project dealing with language also contributed to the development of the sound installation: While on a residency in Phnom Penh in 2014, Arunrak made posters announcing her presence to the neighborhood, which she wrote in Cambodian, a language she cannot speak. Drawing and making images of and with the community thus became her primary form of communication.

Orawan Arunrak. Image from Berlin studio, 2017. Dimensions variable. Photograph by the artist. Courtesy of the artist. © Orawan Arunrak.

As a child, Arunrak would make drawings and exchange them with friends for toys, lessons, and other things. Today, her practice is based equally on her compulsive need to draw and create with humble materials and on her desire to use her practice to connect to people and places. She uses her works and her working process to create new relationships and discover new worlds. Her practice explores her labor in creating art objects and the possibility of using those objects and that labor to relate to her social and physical environment.

Although Arunrak has been based in Berlin since mid-2016, much of her vocabulary and concerns invoke the region of Southeast Asia. The voices in her Berlin installation were mostly recorded in Thai and Vietnamese temples in Europe, as well as in parks and other spaces frequented by these migrant communities. Prior to her relocation to Germany, she spent several years roving across her native Thailand, neighboring Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, and beyond, on a series of residencies and lengthy self-initiated research trips.

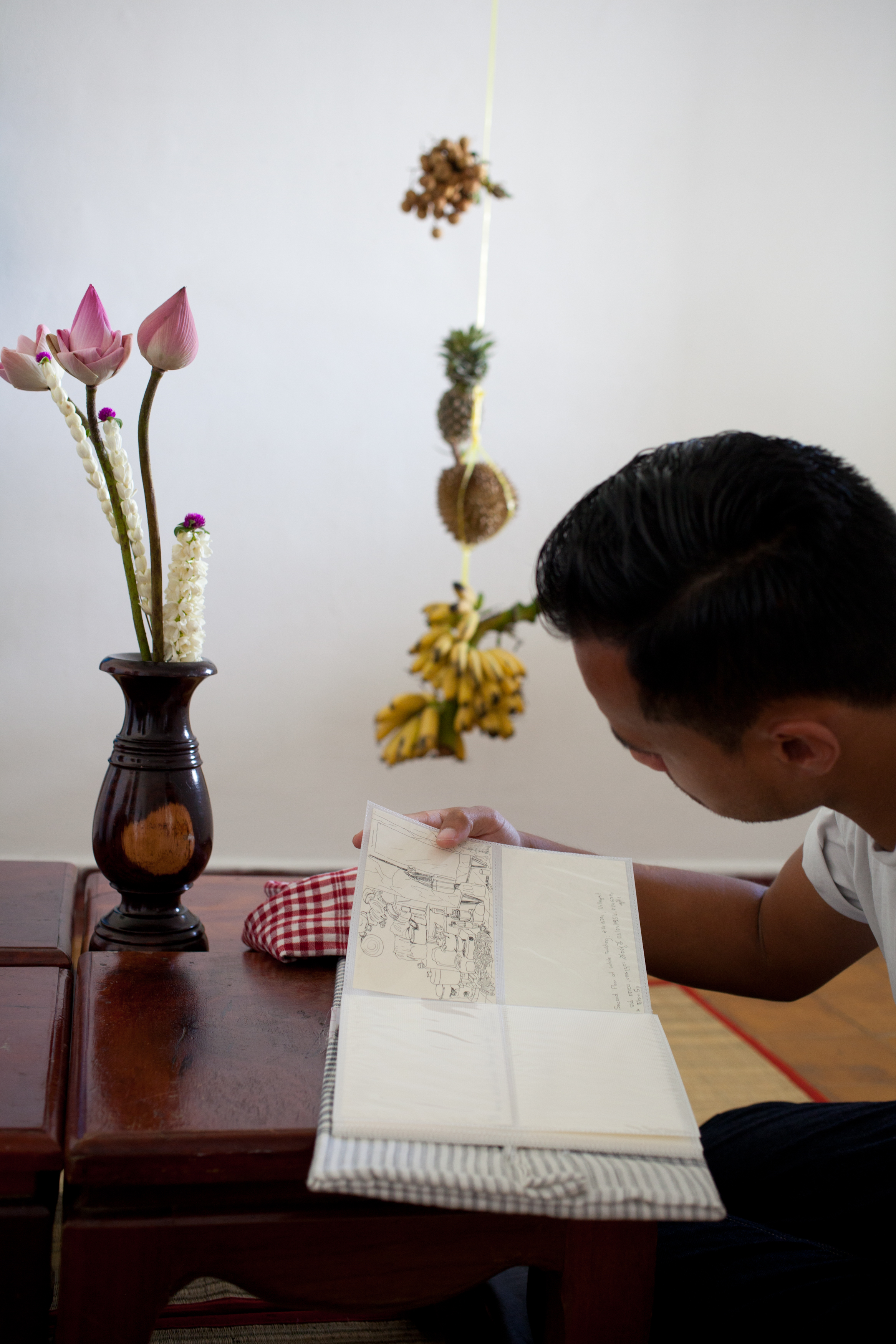

Orawan Arunrak. Come In, 2014. Installation with table, 2 mats, 5 cushions, vase with lotus flowers, fruits, notebook with drawings, photo album with drawings, drawings on the wall. Dimensions variable. Sa Sa Art Projects, Phnom Penh. Photograph by Lim Sokchanlina. Courtesy of the artist. © Orawan Arunrak.

She sees her work, like that of several of her Thai contemporaries—she lists the filmmaker Nontawat Numbenchapol among them—as being rooted in this curious wandering across Southeast Asia. She regards this investment in a regional geography and imagined sensibility as marking a significant shift from the generation of internationally circulating Thai artists before her—the likes of Rirkrit Tiravanija and Kamin Lertchaiprasert—most of whom spent formative years in Europe or the United States. For Arunrak, mobility remains key, but the nature of that mobility and of the questions that compel it have undergone a profound change. In his recent book, Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary, the curator and critic David Teh suggests that the generation of artists like Tiravanija and Lertchaiprasert circulated internationally in a way that set them apart from their predecessors, signaling a move from the modern to the contemporary. Arunrak’s practice points to a second shift, within contemporary-art discourse, which imagines Southeast Asia as a world unto itself.

Orawan Arunrak. Come In, 2014. Installation with table, 2 mats, 5 cushions, vase with lotus flowers, fruits, notebook with drawings, photo album with drawings, drawings on the wall. Dimensions variable. Sa Sa Art Projects, Phnom Penh. Photograph by Lim Sokchanlina. Courtesy of the artist. © Orawan Arunrak.

In conversation, Arunrak has suggested that she sees with “Thai eyes.” Yet her practice complicates the categories of identity and perception implied with that phrase: her work cannot be apprehended only with the eyes and cannot be reduced to any single heritage or site, moving always between zones and relationships. If her work, as she says, is a word, then it is one with many meanings, in many languages, for many people.