New Work: Kerry Tribe, 2017. Installation view, SFMOMA. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel.

Can empathy be taught? The Los Angeles–based artist and filmmaker Kerry Tribe ponders this question in her most recent video installation, Standardized Patient. The work examines the relationship between doctors and patients—or, more accurately, between medical students and actors playing patients.

Commissioned by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art for its “New Work” series, Standardized Patient depicts a number of “Objective Structured Clinical Examinations” (OSCEs). In these simulated clinical environments, medical students practice communication skills with patients portrayed by professional actors known as “Standardized Patients” (SPs). The students take the SPs’ medical histories, ask about symptoms, offer diagnoses, and give recommendations, all the while being watched by professors, who later give feedback.

New Work: Kerry Tribe, 2017. Installation view, SFMOMA. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel.

Tribe’s work evolved from her collaboration with and study of professional clinicians, communication experts, and SPs at Stanford University and the University of Southern California (USC). For this video, Tribe developed four case studies and filled the roles with USC staff participants, medical students, and SPs trained to portray both patient and student characters.

The first scene shows the medical students standing in a hallway, each of them outside a door to an examination room. Over the course of the video, a viewer learns about four patients: a thirty-six-year-old woman in a sharp black suit who is following up on blood work for chest pains and constantly looking at her watch, anxious to get back to work; a seventy-two-year-old woman whose daughter insisted she get a checkup after repeated incidents of forgetfulness; a teenage girl who recently became sexually active and wants contraceptives but agrees to being screened for sexually transmitted infections (and the results aren’t good); and a sixty-eight-year-old man near death.

Kerry Tribe. Standardized Patient, 2017 (production still). Commissioned by SFMOMA. Courtesy the artist and 1301PE, Los Angeles. © Kerry Tribe.

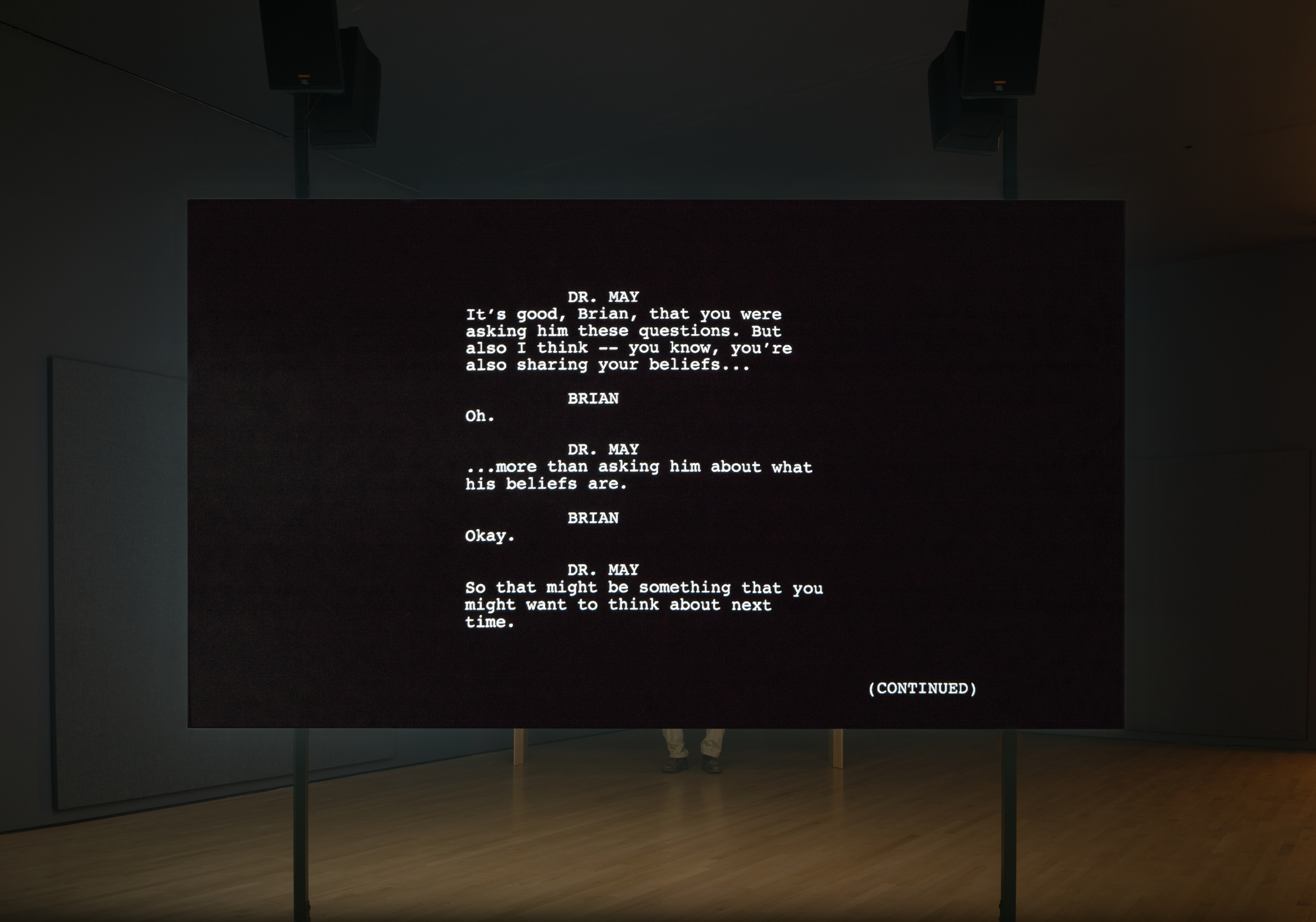

In the last scenario, the medical students stand in a row and take turns speaking with the patient. One student asks about the man’s family. Another starts discussing spirituality with the SP, acting surprised when he says he’s a nonbeliever but proceeding to offer his viewpoint on God and the afterlife. This encounter is cringe inducing, and the professor, while remaining cool and collected, makes it clear that this method is not the way to go.

Intermixed with these scenarios is footage filmed in Stanford University’s School of Medicine. From images of clocks and mannequins, to fluorescent lights and empty exam rooms, this B-roll emphasizes the sterility of the clinical environment and invites viewers to think about artificial and genuine encounters. Hinted throughout the piece is the nature and degree of performance, as both SPs and medical students try to communicate responses that are both empathetic and realistic.

New Work: Kerry Tribe, 2017. Installation view, SFMOMA. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel.

This element of performance is further emphasized by the presentation of Tribe’s installation. On one side of a screen, the case studies unfold. On the other side, supporting materials such as medical-journal entries, patients’ prescriptions, flow charts, and illustrated diagrams offer a text-based narrative to accompany the conversation in the OSCE. This further invites viewers to consider language and communication from a systemic level, at which dictionary definitions complicate the achievement of empathy.

Both sides of the screen convey suspense. Even though everyone is acting, the anticipation of a diagnosis is still nerve-wracking. Many of the SPs react emotionally, crying or widening their eyes in disbelief. Despite the sterile rooms and lab coats, the video captures the players’ subtlety of interaction and remarkable humanness. Because the SPs are so convincing, the medical students respond in surprising, often emotional, ways. In these moments, it is easy to forget that the video is not a documentary, an impression that only collapses when the OSCE ends and the SP, no longer in character, fills out an evaluation.

The brilliance of the work lies in its portrayal of commonality. All of us have had interactions with medical professionals and understand what it is like to sit under fluorescent lights waiting for news, good or bad. Because such interactions are routine, their constructed nature is often taken for granted, and the fundamental humanness of such encounters is unrecognized. And yet these moments have the potential to define empathy, the act of understanding. Standardized Patient is a poignant reminder that practicing empathy is a skill, one that can be cultivated and nurtured so that understanding and care transcends mere words on a page.

New Work: Kerry Tribe is on view at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through February 25, 2018.