Self-image can be a difficult topic to address, with people of all ages and backgrounds. Today, with social media, blogging, and digital autobiographies, we all hope to control the way we are perceived. Who are you—to yourself, to me; to your teacher, classmate, or student; to your friend or enemy; to someone familiar or to a stranger? With each person, does your role change or does their perception of you change? Do you change through this process? Who am I, to you and to myself? How do you see me? Can or should you see me differently? What is a portrait? What does it mean to portray or represent someone? Is it capturing a likeness or depicting a common understanding of someone? Is this honest, accurate, the way we see the world? What about the way we see a person?

These concepts—who one is versus how the world sees one—prompted me to lead a classroom project to explore empathy through portraiture. Teenagers, especially those who may have low self-esteem (as a result of trauma, abuse, or oppression), are extremely self-conscious, and their heightened sensitivity can make a self-portrait project intimidating, for students and teachers alike. But great teaching moments can arise from working through difficult situations. We as classroom leaders must embrace the challenge by deeply engaging our students so they can overcome their discomfort.

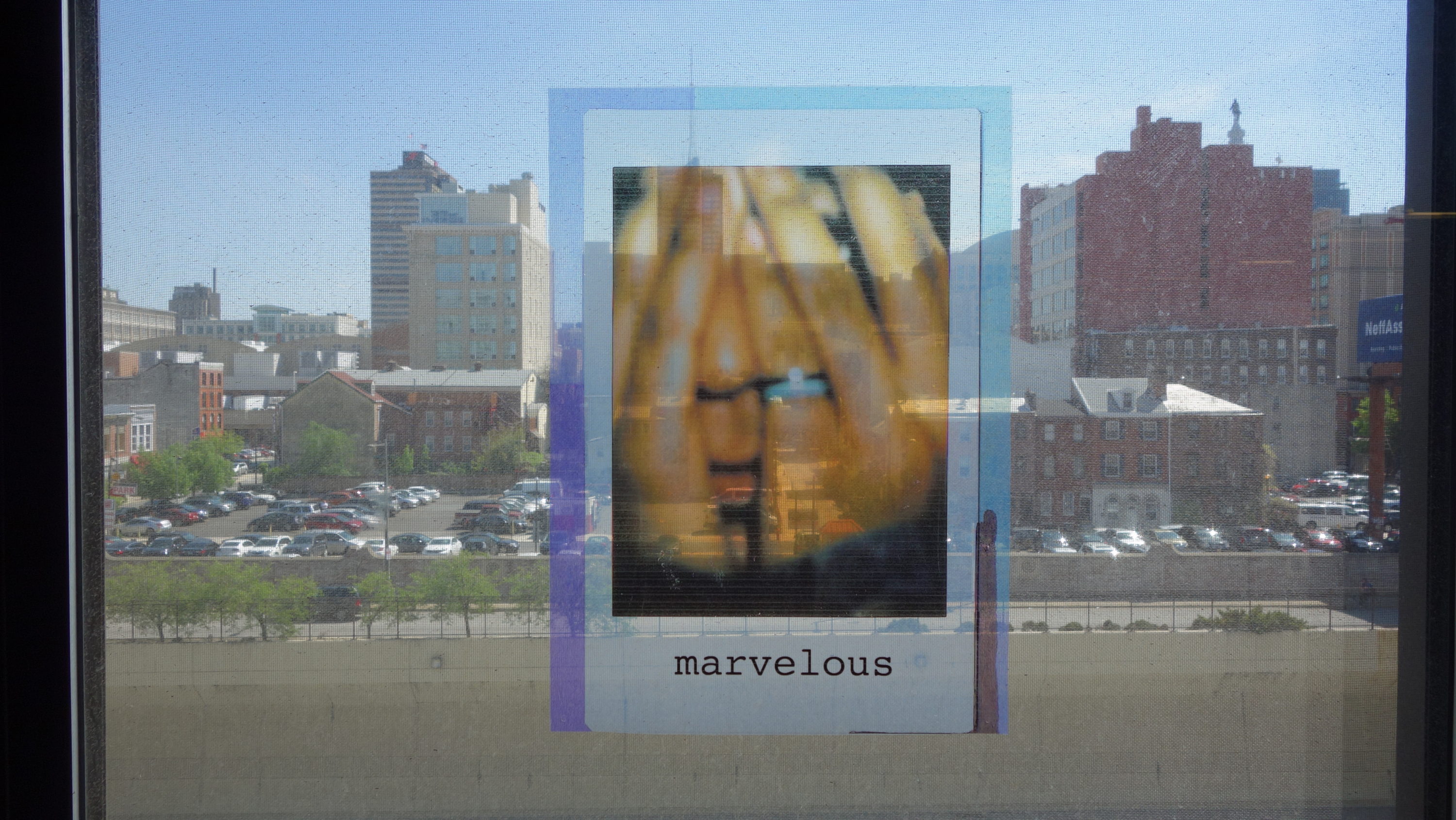

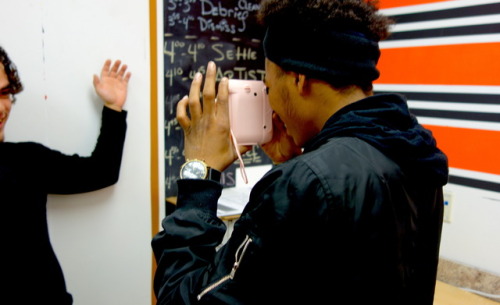

To develop our concepts of empathy, I introduced my students to the work of the artist Carrie Mae Weems. We focused on her historical reenactments through photography and performance and her series of paired images and texts depicting contemporary and historical persons. Her utilization of text, to provide a deeper narrative context for her subjects, was a key element to our lesson. Inspired by Weems’s work, the students created their own self-portraits through collages made with Polaroid photographs and texts. The project’s goal was to help students express their identity and sense of self in a positive way, to help them create confidently and feel hopeful for themselves. I wanted my students to take a stand and define who they were in the world, even through something as simple as a selfie, because change begins with small steps. I always strive to create space in my classroom for my students to explore themselves openly, and I made sure to secure their anonymity within the project, an important aspect to empower them to express vulnerable ideas. In their portraits, the students kept their identities safe by concealing their faces through the strategic placement of the camera, but they revealed their thoughts, insights, and reflections about who they are by their choices of accompanying texts.

The project was important for many of the students as well as for myself, as their teacher. It allowed the students to be truthful and honest, without fear of dismissal. Many of them have been labeled by their community and the larger society—judged according to stereotypes of juvenile offenders, victims of abuse, or homeless people and what these types look like, feel, value, and are capable of—without regard to their uniqueness as individuals. Through my students’ choices of text, I learned so much about them, their traits, and their values. And through the process of demonstrating a work for the project, I learned a lot about who I am and what I value. For an exhibition at the end of the project, we showed enlargements of many of our photographs, and my students proudly displayed their work with confidence and without fear or reservation. These were truthful portraits, and the works’ captions were messages of hope.