Barbara Kruger. Untitled (Shopping), 2002. Installation view: Façade of Galeria Kaufhof, Frankfurt. Courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery, New York. Photo: Schirn Kunsthalle.

Typically when interviewing an artist I arrive with a small film crew in tow but since Barbara Kruger doesn’t agree to on-camera interviews, our conversation was refreshingly intimate. Tucked away in a quiet conference room overlooking midtown Manhattan, Barbara and I discussed her life and work with nothing but a microphone between us. Since the 1980s, and continuing with unceasing relevance, Kruger’s work straightforwardly addresses notions of otherness, power, consumerism, and visibility through boldly graphic text and images in red, black, and white. She’s been listed on Art21’s artist page since 2001—she created an original work with the tennis star John McEnroe for the introduction to the Consumption episode—but this interview presented the opportunity to learn firsthand what drives and inspires her work.

Ian Forster: Your early works have stood the test of time and continue to resonate. Could you discuss the impetus for the work that is my favorite from the early ’80s, Untitled (You construct intricate rituals, which allow you to touch the skin of other men)?

Barbara Kruger: It has to do with the notion of a comfort or discomfort with sameness and difference and that sports, for instance, is a way that men can be allowed to have physical contact that is disallowed in a homophobic culture—not only in the playing of the game but also in the viewing of the game. Sports promote a kind of romance or a group understanding and intimacy about the notion of teams, about men being together and men’s bodies being together. It’s also true of the military, and it’s true of cultures in certain countries that disallow difference and are homophobic and at the same time are engaged in a war for a world without women.

Now, of course, things are different because gender binaries have changed so dramatically in the past ten years, problematizing the assignment of gender itself—which in many ways, for many lives, has been very productive and emancipatory.

Barbara Kruger. Untitled (You construct intricate rituals which allow you to touch the skin of other men), 1980. Photograph; 37 × 50 inches. Courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

© Barbara Kruger

IF: You’re often discussed in the context of feminism. How do you define your relationship to that movement?

BK: Well, of course I’m a feminist, but I speak about feminism as a plural. There are feminisms, and those feminisms are acted out in terms of site specificity: context, race, class, gender, location. They also connect with a larger term, intersectionality, which is commonly used now but which I’ve always understood organically.

There is always a connection between issues of race and gender and class. They don’t ever exist separately, and people who feel that they live them separately are really not understanding the multiple forces that have impacts on their identity and their lives. You just can’t talk about sexuality and gender without engaging the complicated issues of race, and you can’t talk about race without engaging complicated, under-recognized issues of class. And it’s wrong to trivialize any one of those things at the price of the other. We saw the results of that with the election of Trump: that’s what happens when you don’t understand the expanse of ideas and faces and skin colors and income brackets that comprise value systems.

Barbara Kruger. Installation view of FOREVER, Sprüth Magers Berlin, 2017. Production still from the Art21 Extended Play film, Barbara Kruger: Part of the Discourse. © Art21, Inc. 2018.

IF: How do you stay up-to-date with these complicated, evolving issues? What media do you consume?

BK: I think television was and is very important, and now, of course, I read online all the time: websites of newspapers like the New York Times, LA Times, The Guardian, Washington Post. I go to aggregators, but I also go to a lot of right-wing websites, and I watch Fox, of course.

IF: Why do you go to the right-wing websites and watch Fox?

BK: Because I don’t live in the liberal bubble that brought us the regime that we have now. People in that bubble were really ignorant of the forces around them and how they were gathering strength. And I knew that to be the case by reading Storm Front and InfoWars and watching Fox for years—especially now with the host Jeanine Pirro and the campaign to discredit Robert Mueller.

IF: So it’s research, to see how they’re using media?

BK: No, I observe their use of language and how easy it is to con people who want to be conned and the incredible global power of White grievance and White rage.

The failure of so-called progressive culture or the left is that people were closed within a bubble. And now it is promoted even more in what are called silos—in the right, the left, the middle, by our online identities, by our bookmarks, by where we go. We used to read physical newspapers and read everything—business, sports. Now, people read online and don’t read as rigorously. But you know where you go. If you see people’s bookmarks, you can pretty much read their autobiography. That’s interesting but also frighteningly reductivist.

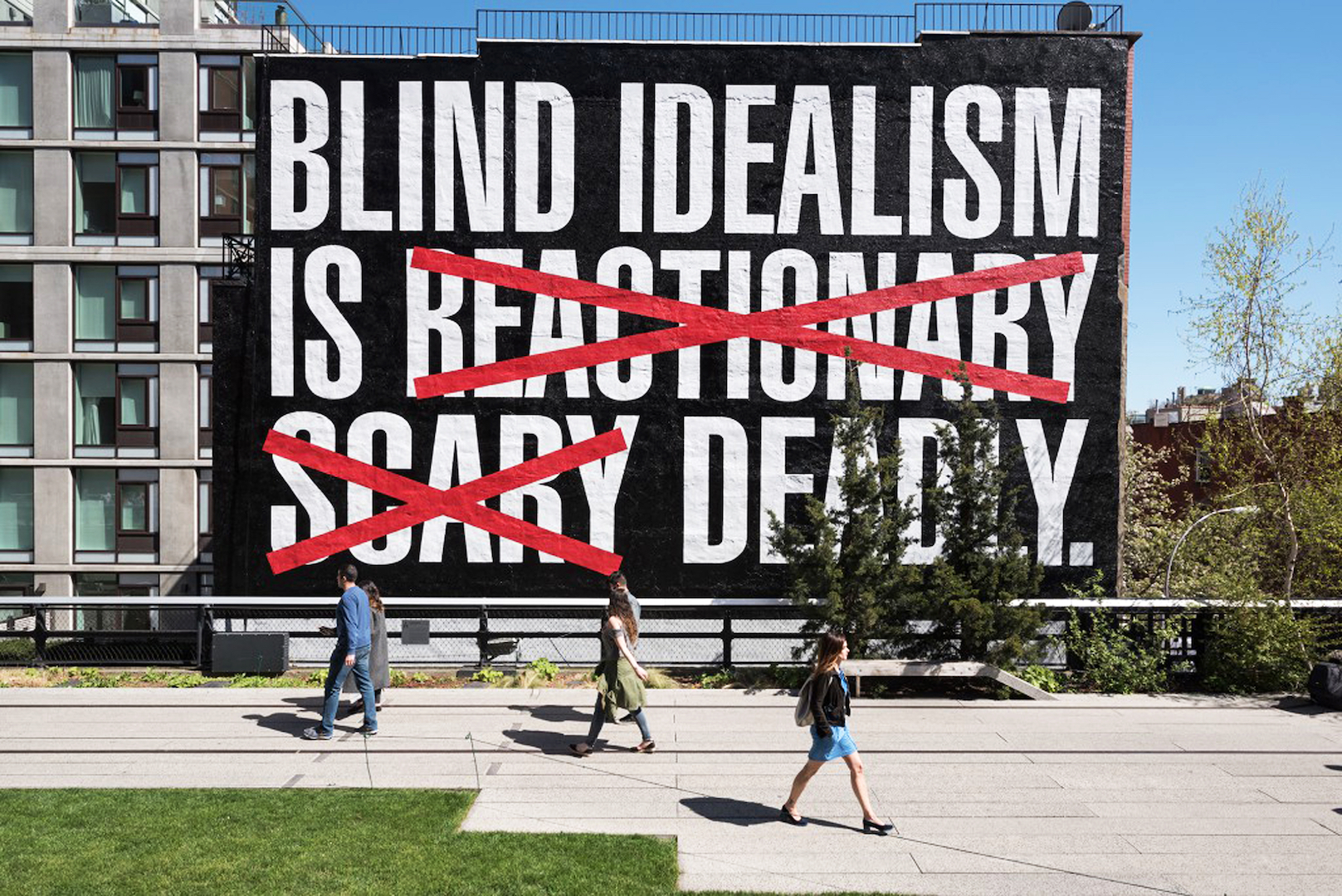

Barbara Kruger. Untitled (Blind idealism is…), 2016-2017. Installation view: The High Line, New York City. Courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery, New York. Photo: Timothy Schenck.

IF: What do you see as the power and potential of art, perhaps in contrast to the conventional media?

BK: I’ve always had a very broad definition of art, and it always struck me as funny that any piece of canvas with some pigment on it is called art, and some movies or forms of music are considered art and some aren’t. It’s complicated, and I don’t know the answers. But I do know that art is the creation of commentary. I think that art is the ability to textualize or visualize or musicalize one’s experience of the world—not on a diaristic, literal level but in a way that creates a commentary about what it feels to live another day.

The goal for every human being, including myself, is to live an examined life—to really think about what makes us who we are in the world and how culture constructs and contains us. That’s what I’m interested in.

Read the full interview with Barbara Kruger on Art21.org.