Black Lunch Table. Black Lunch Table, 2005. Activation; dimensions variable. Photo: Angela Hennessy. Courtesy of Black Lunch Table.

“…you’re moving in these worlds where you are switching all the time, but the table, the lunch table, was always that place of respite, where you get to touch base with folks who you don’t have to explain much to…” —Shervone Neckles1

Thirteen summers since the original convening of the Black Lunch Table (BLT), we look back on the project’s history and evolution and consider its future trajectory. We recently reconvened many of the original participants to discuss how our lives, our conception of Blackness, and our relation to lunch tables (both physical and conceptual) have evolved since that first event. Directly on the heels of that reunion, we embarked on our first engagement on the African continent, hosting events in Cape Town and Johannesburg. And we’ve just launched the beta version of our website, which will afford the public access to a sample of the documentation of four years of BLT roundtable conversations.

We imagine the present work to be a creation of a matrix—a process, a language—by which we aggregate people, locations, conversations, languages, and data. The discussions are recorded, transcribed, and assigned metadata for inclusion. The BLT archive is a living one, documenting temporally and geographically specific discourses. In this project of investigating the phenomenon of self-segregation, the compositional elements are self-reflexive or self-renewing.

Archiving past conversations informs the creation of new prompts for future conversations. Since the metadata tags are endlessly editable, the relational metadata create flexible definitions for terms used within our archive and shared with others. These definitions will inform the interpretation of the transcripts and audio. The archive will inform the direction of cultural research, which will in turn inform the content of future roundtable conversations. The potential for creation of meaning, and for the expansion of our project, is infinite and a metaphor for how we envision the project’s future.

When we met in 2005 at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, we began the project as tricksters, wondering what would happen if we segregated a purportedly idyllic space so that it mimicked spaces we had experienced in our lives. We thought about perception and self-identification. Claiming this space reified our presence in the community and exposed the problems around who gets a seat at the table. There, we mulled over ideas of civic responsibility, of self-segregation, and of being cultural gatekeepers.

“…this idea of bringing what is very natural to us into an art space and centralizing us in that space…reminding folks that this is what is real to us…” —Shervone Neckles

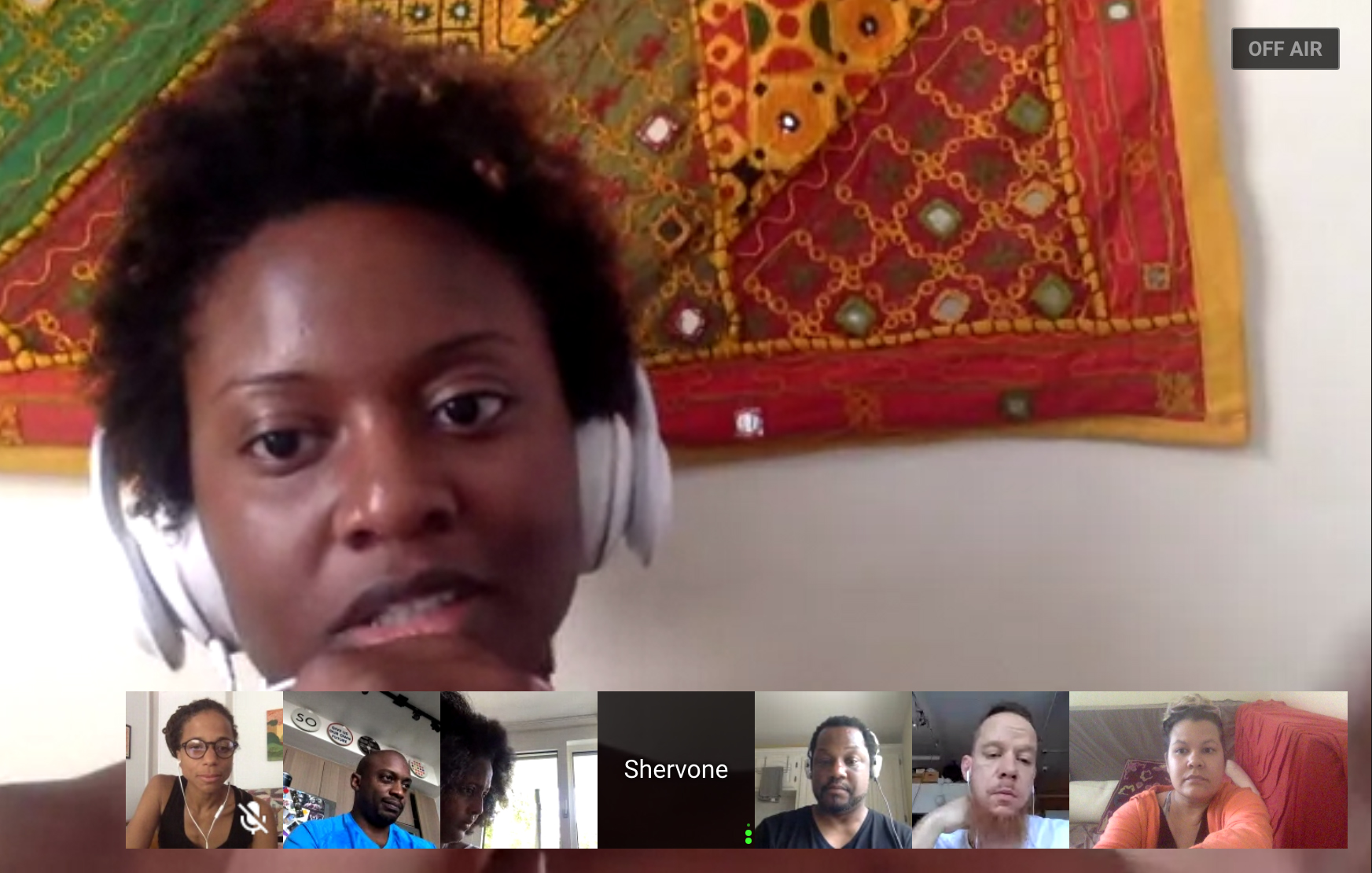

Black Lunch Table. Black Lunch Table Reunion. 2018. Hangout activation, dimensions variable. Photo courtesy the artists.

The event catalyzed a series of conversations with our excluded white friends about its apparent subversion and disruption, which teased out issues related to the privileges they lived with daily. That first convening still echoes for each of us.

“I do remember certain people were really upset…”—Loul Samater

“My goal became: to talk about the problem of whiteness—the problem of the toxicity of the belief in whiteness—and the support for whiteness that so many of us live with, all the time. In an environment like Skowhegan, you have an overview. You’re not in it; you’re sort of outside of it—seeing the way that other white participants were so uncomfortable with Black people having some agency and some collaborative intent that didn’t center on [white people].” —Steve Locke

“The Black lunch table at Skowhegan, for me, was kind of interesting because I went to a high school where we had a white lunch table. It was a predominantly Black environment, where the other table was the white kids and the Asian kids. So, I was being introduced to a way of communing around Blackness, which I would experience more and more once I moved to New York, right after Skowhegan.” —Yashua Klos

Departing the United States and bringing our project to the Continent felt at once like a homecoming and a leap into the void. The parameters for discourse around Blackness are known—or at least fathomable—for us in the States. Our and others’ perceptions of our racial identities were the basis for the project, at its inception. Expanding the parameters to include international discourses on the subject of race required a reevaluation of our self-images, and of the foundational principles of the project, as well as a renovation of the textual architecture upon which the entire thing is built.

We understand Blackness as a mythic concept, as a social construct, and as a lived reality as it relates to our subjective experiences in the United States. Our lineages are composed of negro, coloured, African American, and Black. Our lineages comprise white, Native American, and undocumented traces. As conspicuously Other, we have self-consciously chosen to sit or not to sit with our classmates or colleagues at Black lunch tables.

“I don’t really believe in race, so that’s my own challenge with the BLT as a concept. I think that Blackness is more of a frame of mind than it is an actual reality. It’s the frame of mind that maybe shapes our realities.” —Hank Willis Thomas

“The fiction of race has poisoned all of us. We’re all living with the fiction. We all know it’s not real. We know it’s constructed; we know it’s insane. But it also is a way: it’s the color line that divides the living and the dead, for a lot of us.” —Steve Locke

“What does it mean to identify as Black?” This question became a prompt for our roundtables. We found it necessary to explain the concept of a Black lunch table to a South African audience, which found it foreign.

Black Lunch Table. Black Lunch Table: Artists’ Roundtable, Market Photo Workshop, Johannesburg, 2018. Activation; dimensions variable. Photo: Jina Valentine. Courtesy of Black Lunch Table.

In South Africa, we are American, Black or coloured, of the African diaspora.2 So, we are compelled to reconsider the parameters for a discussion among artists of the African diaspora. Is identifying as Black an acknowledgement that one is perceived as such, or is it a claiming of an identity and an affinity with a culture? As Black Americans, we were born of generations afflicted by the toxicity of colorism, classism, and social mores enforced by a white government and bequeathed the epigenetics of slavery. In South Africa, the conversations around racism, classism, and nationalism revealed an equally complex yet very different history of racial trauma and cultivation of the Other. That history is uniquely South African and sets its people apart from other populations on the continent.

As Americans, we appropriate a Blackness derived from our perceptions of African culture, and we then market it back to Africans through pop culture and commodification. We look for Wakanda and a unification with our history in Africa. The fiction of a monolithic, homogeneous Black experience permeates popular culture in the West. Perhaps navigating a white world as one who is conspicuously Other is our common experience, bridging cultural, national, and class differences. Of course, the terms that define Otherness are established by those who’ve secured their roles as authors of the people’s history: the former or current colonial powers. We consider the ripple effects of colonialism, of neocolonial powers, and of the rise of nationalism in the West, as well as how power balances and international influences are more determined by capital than by brute exertions of force by one country over another.

What does it mean to identify as Black? Or coloured? Or of the African diaspora? What does it mean to live in a world where we unconsciously or consciously require such social determinations and divisions? Are ethnic hierarchies and labels impediments that we collectively, as a human race, wish to overcome? Is there value and power in claiming spaces of affinity for the discussion of our shared struggles and successes?

Authoring the dominant historical account means determining who are Others and the terms by which they are treated as such. We determine that the Black Lunch Table is a relevant and critical gesture to disrupt this production of the dominant narrative.

1. All quotes in this essay are from the Black Lunch Table Reunion, held on June 30, 2018, via Skype. A full transcription will be available at blacklunchtable.org.

2. Conversation with Ghairunisa Galeta, Ashley Whitfield and Thuli Mlambo 2018, oral communication, 28th July.