Sharing stories of growing up in South Africa, William Kentridge reveals how early experiences influenced his drawing style and describes similarities and differences between South African and North American histories.

Editor’s Note: In celebration of the release of Art21’s latest book, titled Being An Artist, we’ve chosen to re-publish the following interview from the compendium on the Art21 Magazine. Interviewed by Art21’s founder Susan Sollins at James Cohan Gallery in New York City on November 9, 2009, William Kentridge is the subject of the only Art21-produced feature film to-date, William Kentridge: Anything Is Possible. Sollins spent hours interviewing Kentridge, both in the U.S. and in his native South Africa, collecting insights into the life and work of one of influential artists of our time. With our recent ninth season of Art in the Twenty-First Century, Art21 has continued to share the stories of South African artists, in an episode devoted to artists working in Johannesburg. We are pleased to present this interview here, for our Magazine readers, as a rumination on the deep act of investigation that being an artist takes—and as a bridge between Art21’s past and present. Kentridge will present a new commissioned work, “The Head and the Load” at The Park Avenue Armory in New York City this December.

Art21—What is your earliest memory of making things?

Kentridge—I started off drawing, the way all children draw, which is not unusual. But there were a couple of early experiences that I think were not so usual. One was that I made a really beautiful, bright, colorful painting when I was five, using gouache. It was a splatter painting—like a five-year-old doing Jackson Pollock. A lot of fuss was made over that painting. I don’t know what I knew about color then, but I certainly don’t know it now.

The other experience was that, very early on, I was taken to an elderly friend of my grandparents, a Welsh artist named Matthew Whitman, who was painting in Johannesburg. I think I showed him some of my drawings, and he gave me a drawing list, explaining how to draw the veranda of his house and where to put the shadows. I was happy to be watching him looking.

I ended up as an artist. It wasn’t a decision I made; it wasn’t a choice. It was what I was reduced to.

While in university, I realized my grandfather’s advice that painting should just be a hobby didn’t hold much water. But I thought I would do drawing while I wait for the revolution. After the revolution, then I’ll see what is needed. Will I be the people’s commissar for beautiful objects? What will I become; what will be my role? I couldn’t imagine, for example, that the legal system would be the same after the transition as before, which was incredibly stupid. I was drawing while waiting to see what I would become.

I went from drawing into theater school because I was acting at the same time. When that was a disaster, I started working in the South African film and television industry, as a props person and then as a production designer.

Then you started working as an artist?

After working in the film and television industry for a couple of years, I got back in the studio, making drawings, thinking I’d do it for a while and then do something else and eventually discover what I should be doing. At a certain point, a friend of mine, to whom I’d always complained about what job I should get and what I should do, said to me in no uncertain terms, “You’re now 25 or 28, whatever age you are; you’ve never had a job; you are unemployable. Stop talking about someone giving you a job. No one will give you a job. Do what you’re doing and make a success or a failure of it, but stop imagining that there’s going to be a different trajectory for you.” I said, “Okay, I’ll make drawings, fine.” I ended up as an artist. It wasn’t a decision I made; it wasn’t a choice. It was what I was reduced to.

When did you know you were an artist?

When I was about 15, people wanted me to say what I thought I was going to study, what I thought I was going to be when I became an adult—like a lawyer, engineer, deep-sea diver, marine biologist. In one survey, I wrote that I wanted to be a conductor. Somebody said you have to be able to read music to be a conductor, so I changed that one.

Was art always there, in you?

In retrospect, it was always there. It was not something I suddenly started in my late twenties. It had started very early on, even though I’d stopped for a couple of years. Part of me knew I only existed if I made some kind of external representation on a sheet of paper. I think there has to be some psychic need like that for anyone to spend their life making drawings. It has to be about you not being enough. It’s about knowing you exist only through other people’s responses to work that you have done. I think it’s why artists are so bad at dealing with critics because a criticism of the work is not just someone thinking the work is bad. It’s an annihilation because, as an artist, one of the ways I know I exist is in making this and showing it. If people don’t want to look at it, it doesn’t exist; you may think you’ve done something, but there’s nothing there. It’s more than someone saying you’re wearing ugly trousers today. It’s someone saying there’s a fundamental way in which you cease to exist.

Did you have artistic family members?

My mother was a lawyer. She says, as in reverse genetic engineering, she became an artist after I was an artist. She spent the past many years painting and drawing with a lot of passion. If one does it well, it becomes an intense kind of looking in a difficult exercise.

What was your family’s political history?

On my father’s side, my grandfather was a politician; he was a member of parliament for forty years. He began as a socialist, standing for the Labor Party, and after the revolution was berated as a sympathizer of the new Soviet government. Obviously, South Africa had a Whites-only parliament then. In the 1922 strike by White miners, protesting the danger of Black miners taking their jobs, the logo or one of the slogans of the strike—which tells a lot about South African history—was, “Workers of the world unite and fight for a White South Africa.”

My family was involved with the legal battles against apartheid, including the Sharpeville massacre and the treason trials in the 1950s and early ’60s, which my father was a part of, and later, with the Legal Resources Center that my mother founded. Ours was a house in which one was aware of South Africa being an anomaly. Other boys in my classes assumed Whites had the rights and Black people didn’t have the rights, and that was the way nature and the world was.

My family was not at the forefront of the liberation movement in South Africa, but I grew up very aware of the distortions of the society and of the unnaturalness of the world I was in. Of course, all White South Africans benefited from the privileges that were their birthright, which is very different than what’s happened in the past sixteen years, when there has been a remarkable transformation.

The hope is that people in the United States can make the imaginative leap to understand the different context in South Africa

It sometimes strikes me that, in terms of understanding or getting a historical perspective on how things connect to each other, American audiences have been much less attuned than audiences outside the United States. Perhaps it’s because American history fills up the heads of a lot of Americans, leaving no space for anything outside of it, or it’s a different sensibility. For example, in New York there have been recent museum exhibitions of the work of Gabriel Orozco, Tino Sehgal, Marina Abramovic´, and me. None of the four of us are from North America; we have a different sensibility, which is not obvious or necessarily straightforward. It seemed to me a lot of people have understood the connections.

There are probably a million people who do not know what you’re talking about.

In South Africa, there was always anticipation that there’d be this violent upheaval and transformation from the apartheid state to a different state, which would be a socialist state, of one form or another. The Communist Party was very strong in the underground movement in South Africa and still is part of the coalition of the government in power now. The ideas of Marxism, socialism, and radical transformation, of understanding a long history of transforming society—they didn’t start with the civil-rights movement in the 1960s but predated it by a hundred years. That comes from a different strain, from Eastern Europe and into southern Africa. This fundamental way of understanding the world was clear in Johannesburg.

I’m aware of some similarities between South African history and North American history. A lot of Black South Africans have taken courage from the civil-rights movements in North America, in the United States. But I’m more aware of huge differences between traditions and trajectories that operate in the two places. It’s possible for South Africans to understand the context of American transformation and radical movements. The hope is that people in the United States can make the imaginative leap to understand the different context in South Africa as something that is not identical to what Americans have.

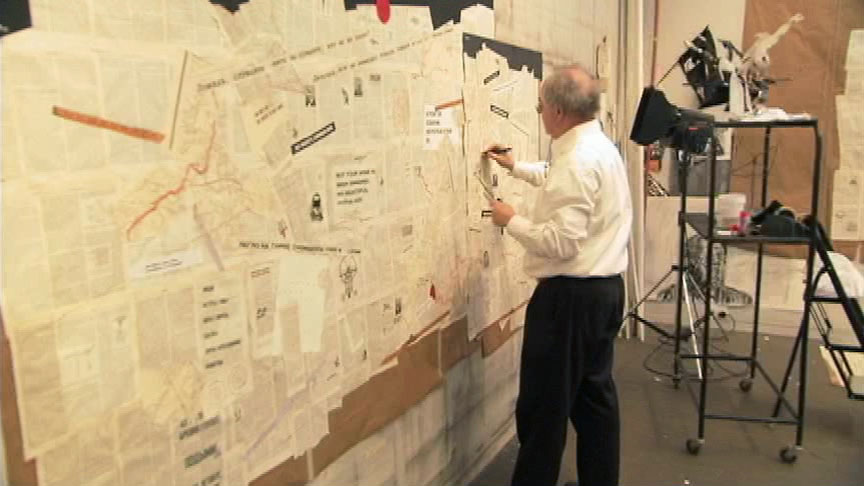

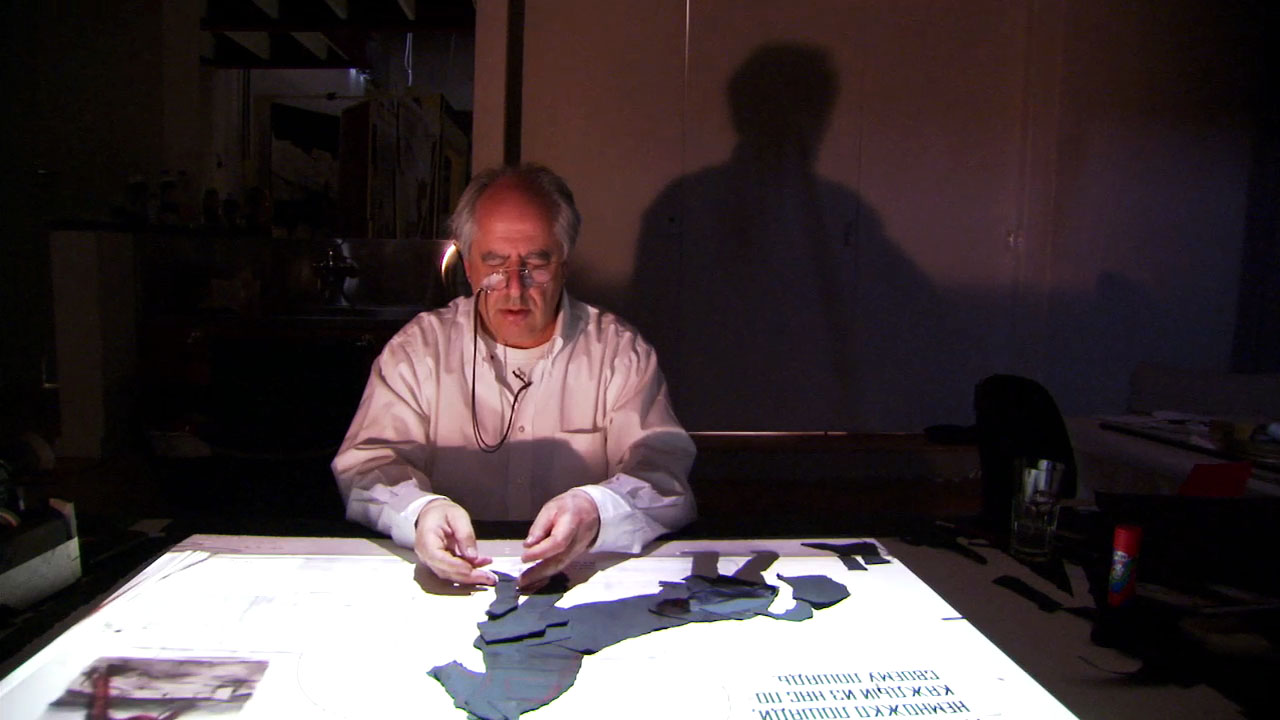

Getting back to your art: working in film opened the door for you.

Yes, because it gave me a sense that it was possible to work without a plan in advance and to make it without first writing a script. If you work conscientiously, and if there is something inside you that is of interest, that is what will come out. You will be the film; the film will always be you. A lot of the work that I’ve done since starting to work with film, even if it’s not using that technique, has certainly used that strategy. It had to do with understanding that moving images rather than static images are a key thing for me. The provisionality of the drawings, the fact that one stage of the drawing is going to be succeeded by the next stage, was very good for me, as someone who’s bad at knowing when to commit something to being finished. In making the film, the drawing would go on until the sequence was finished, and that would be the end of the drawing.