The sense of place achieves its clearest articulation through narrative, providing the thematic drive and focus of the stories that people tell about the places in their lives.

—Kent C. Ryden, Mapping the Invisible Landscape.

I was born in 1981 on an Air Force base in Blytheville, Arkansas, a small rural town where my mother Deborah Ann was born and raised, as were her mother Marvis and her grandmother Signora. Cotton fields are clear in my memory—they often appear as a white haze in the distance—and visits back to Blytheville happened near harvest season in late August. In my mother’s family, no one spoke of the fields until I was older and began to hear stories of my mother chopping cotton for spending money, to buy a pair of white pants to wear to school, in the 1970s. It was a difficult image to picture; I know her as an “ain’t working outside in the heat” kind of woman, but perhaps her experience of working in the fields is the reason.

“How do our families react to artwork that references their lives, their ancestors, and to the circumstances that have resulted?”

One exhibition that triggered in me a sense of nostalgia and of family was “Beverly Buchanan—Ruins and Rituals” show at the Brooklyn Museum in 2017. Her sculptures echoed the shacks and wooded landscape of Blytheville. I felt my family in Buchanan’s works; I felt placed directly on the streets of the city, in some of the poorer Black-populated areas that were once lined with homes and now stand bare. Buchanan’s exhibition made a memory and a legacy tangible.

Kevin Beasley. A view of a landscape, 2019. Resin, Raw Virginia Cotton, Altered Garments, and Sound Equipment. Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kevin Beasley’s Raw Materials,” 2019 © Art21, Inc. 2019

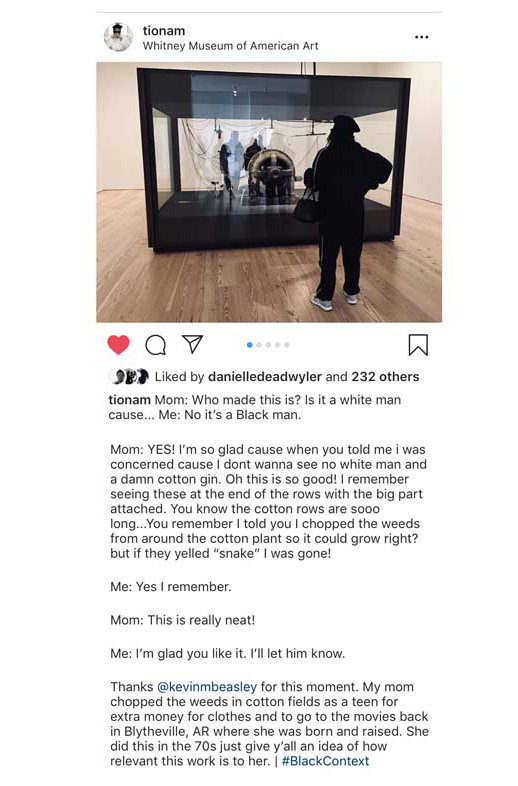

I had a similar experience when I visited Kevin Beasley‘s solo exhibition, “A view of a landscape”, at the Whitney Museum in December 2018. Seeing the show’s restored cotton-gin motor brought to mind a flood of images of my mother working in a field although I had never seen her do this work. I had been unable to share my experience of Buchanan’s exhibition with my mother, so I was determined to bring her to Beasley’s exhibition.

Social media screenshot, features A view of a landscape (2019), by Kevin Beasley. Image courtesy of the author.

“My curatorial and art work is sourced from my mother’s relationship to her surroundings.”

On January 13, 2018, we visited the Whitney Museum, a first for her. We made it up to the top floor, to the motor. It was silenced by a glass vitrine, and the room was oddly empty; both aspects allowed my mother to spend some time in silence and in solitude. I shared a few images of her viewing the motor on my private Instagram account, captioned with our brief spoken exchange in the galleries. My friends and I often think about how our families will react to artwork that makes reference to their lives, to those of their ancestors, and to the circumstances that have resulted. Within a few hours, my Instagram post was flooded with likes and comments. This proved to me that artworks like Beasley’s illuminate a shared history, one that is not so rare, and that there is a desire for more.

———————

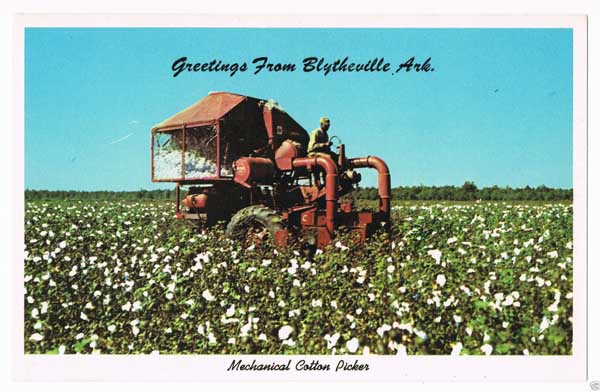

My mother’s first job, as a sixteen-year-old, was chopping the weeds surrounding the cotton plants—a task known simply as “chopping cotton.” It was a time she rarely discussed. Her work in the cotton fields came more than one hundred eighty years after the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, one hundred ten years after the abolishment of slavery in 1863, and only thirty-one years after the mechanical cotton picker was formalized and used in Arkansas, in 1944. The picker was the machine that my mother heard most during harvest; it stood at the end of the rows in the field. The entire cotton gin was housed by a much larger structure, and she was familiar only with its exterior.

After we visited Beasley’s show, I learned that one of the largest cotton gins in the United States was located on the western edge of my hometown. Finally, I was presented with an opportunity to ask my mother about her time in the fields, and she related some of her experience:

Chopping cotton was one of the first big jobs I had. Everybody knew: if you wanted to make some money, you chop cotton. I started out at age fifteen or sixteen, at fifteen dollars a day. You had to go down and ask Mr. Charlie Whirl if you could ride with him on the bus, or truck, or whatever [vehicle] he was taking. [He was] one of the many men in the area who took people to work in the fields. If he didn’t know you, you couldn’t go with him, but he knew our grandma.

Your day started at 4 a.m. You’d ride forever, it seems like, and arrive at the field around 6, at sun up. It would be so hot you’d have to take a straw hat and layers of clothes, a t-shirt and a long-sleeve shirt, or the sun would burn you.

You were given a hoe and instructions on how to chop the weeds from around the cotton so it could grow, because it was really low to the earth. We stopped at 5 o’clock, when the white man would bring the money. I would give grandma some even though it wasn’t a lot, but we didn’t have a lot. If [someone] yelled, “Snake!”—because there were snakes in the fields—I was done and would sit on the bus all day. I don’t do snakes.

——————

Much of my curatorial and art work is sourced from my mother’s relationship to her surroundings, her memories of my ancestors—primarily of my grandmother Marvis, who died when she was only thirteen years old—and my family’s history in the American South.

My practice considers three interrelated aspects of culture: artifacts, sociofacts, and mentifacts. They are foundational to my investment in Black mentifacts (shared ideas, values, or beliefs). No matter how deeply I research document-based archives, I always make reference to a grouping of people or a singular person, to seek out memories. I then try to create a form of material culture from the space between truth and fact, a space of conjecture that I dwell in conceptually. Everything I’ve ever produced must be rooted in a sense of feeling sourced from a Black mentifact, as opposed to just a happening or occurrence in the past or present.

In 2018, I pivoted my work’s focus to Black social and architectural spaces as sites for cultural innovation, relief, and pleasure. In March and April 2018, while in residence at Recess, as a part of the Session series, I transformed the exhibition space into a juke joint, built by hand, called “Shug Avery’s Kiss”, a reference to the character Shug Avery in Alice Walker’s book, The Color Purple. I curated a program of events that included: letter-writing workshops with fellow Black women; an intimate discussion about love with the artist Chloe Bass; and workshops on religion and spirituality with my friend Ash Tai, on sisterhood with my youngest sister, and on friendship with my friend, Keondra. In addition, I hosted three live jukes, rooted in presentation and collaboration: in one, I made a pair of pants with the artist Diamond Stingily, and the other provided me the opportunity to collaborate with my mother, by inviting her to conduct a wig-making workshop, using me as the hair model. In recreating this community space, a conversation was started and a conversation was preserved.

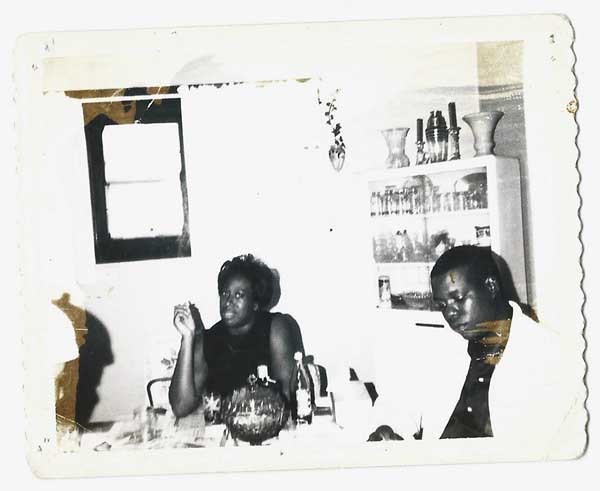

Tiona Nekkia McClodden and her mother as a part of Shug Avery’s Kiss (2018), at Recess. Courtesy of the author.

The abstraction, or rather extension, of that installation also paid homage to not only the juke joint as a historical site of Black artistic creation and social engagement but also to my grandmother Marvis, who frequented jukes after working in a shoe factory in Blytheville. Photos of her were placed on the walls of the juke, the only images of her that I have seen in full clarity. Before I built the installation, I went to Greenville, South Carolina, to speak with my mother and her sisters about the juke joints they had visited or heard of. They shared their memories of the smell of the wood, the alcohol, the porch lights, and the music, which informed how I sculpted the Recess space. My grandmother’s images served as references for color, and Shug Avery was the muse.

Vernacular architecture—and specifically Black vernacular interiors—is often left in an impermanent state, only existing within memory, as most of the buildings, homes, and jukes are no longer standing. They have passed away, just like their owners, who are primarily elders with no heirs interested in taking over such a complex space in a modern society.

For my mother, just the sight of an object that she had never seen—the cotton-gin motor is the interior of a machine, heard but meant to be hidden—reminded her of a time, of a place, of a labor. In the Whitney exhibition, the motor was encased to stifle a sound that would cause one to leave before experiencing the whirling cavity, a condition that also enshrined its power. The sound separated (much like the cotton from the seed) the slab sculptures presenting a contemporary fossilized history of Blackness and its relation to cotton—from flower to t-shirt, to my mother’s white pants—and made transparent our proximity to this flower and our participation in this labor. To me, this is the success of Beasley’s installation: it is accessible to those in direct proximity to the landscape surrounding it, to the exterior of it all.

Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kevin Beasley’s Raw Materials,” 2019 © Art21, Inc. 2019

After my mother and I spend some time with Beasley’s cotton-gin motor, we walk to the museum café. She is clearly overwhelmed, and we spend much of our time in silence, watching people brave the winter cold to take pictures on the balcony. After taking a sip of her overpriced tea, she looks at me and says, “It’s really cool that this is in this museum. I remember being right there in the field.”

Me: What years were you in the fields again?

Mother: Oh it was ‘75, ’76, I reckon..

Me: Wait, so only 6 years before I was born?

Mother: Yep, I suppose that’s right.