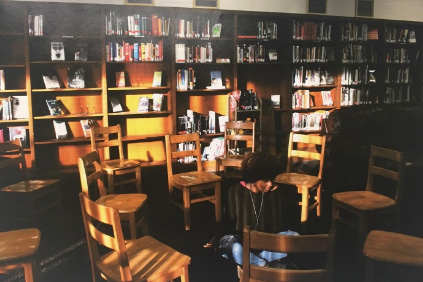

Production still from the “Extended Play” series, “Julie Mehretu: Politicized Landscapes,” 2017 © Art21, Inc. 2017

Last year, when I watched for the first time the Art21 Extended Play episode, Julie Mehretu: Politicized Landscapes, I was overcome with its power and beauty. The short film documents Mehretu creating large-scale abstract landscape paintings for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). The artist explains the process and concept for the contemporary paintings and collaborates with the jazz musician, Jason Moran. The film presented so much, with themes of the artist’s indicting history lesson, of collaboration, and, above all, the beauty of the work. Mehretu is fearless in her confrontation of the past and present state of the country. The film shows an artist making her voice heard through the work.

Students explored the originating question—what is a landscape?—which blew the door open.

For my students, using art to question and address these important issues could be the most important lesson of the film. One of the many ways that I use the Art21 films is for inspiration and as jumping-off points for drawing. In one assignment, the students watch an Art21 digital film and then respond to it visually, in their sketchbooks. I decided to show the Mehretu film to a second-year drawing and painting class of tenth through twelfth graders. In a class session before we viewed the film, I gave the students some background readings on the the Hudson River School and the concept of Manifest Destiny, two topics that Mehretu mentions as influences for the work at SFMOMA. After viewing the film, we had a classroom discussion, starting with the question: What is a landscape? Our conversation explored the conceptual breadth of the word landscape—from the current political climate to social justice. From these discussions, it was apparent that I needed to give the students more time and space to make art with these questions, to make more than a sketch.

Production still from the “Extended Play” series, “Julie Mehretu: Politicized Landscapes,” 2017, © Art21, Inc. 2017

In a second assignment, I asked students to create a piece that explored the originating question—what is a landscape?—which blew the door open for these inquisitive students. I had no idea how far the students would push the theme, with their ideas and choices of media. The students made this project their own inquiry and went in different directions and ranged from traditional to conceptual approaches. They used a range of media: traditional drawing and painting materials, photography, play dough, and so forth.

One student, Terisa, questioned what she called the “landscape of American education.” Terisa made audio interviews of four close friends, in which she asked their opinions on the state of public education in this country. The interviews presented honest and informed responses. For example, another student, John, said:

As a country, as a culture, we value education in a different way than we ought to. Education based on achievements rather than knowledge is what you see in American society…the flaws in our educational system lie in not the education system itself but in the culture of America.

Terisa paired each interview with a photograph of the speaker, seen out of focus or in the shadows, somewhere in the school building. Making the interview subjects hard to see was meant to reflect their feelings of unimportance to the system. Terisa’s work gave the subjects a space for thought and contemplation on their experiences. It was wonderful to see how she had organically made a social-practice artwork without knowing what social practice is; it has inspired me to create a unit on this genre for this school year.

As she interviewing these friends, Terisa told me that what they said made her think about and question her own views—exemplifying the significance of teaching with contemporary art.

Art21 films are the contemporary tools of my trade, and incorporating the Julie Mehretu film in the classroom was a joy and inspiration. I watched students reflect on Mehretu’s ideas and process. It was important for me to see my students think about and work as contemporary artists, to work toward their own inquiries and, in Terisa’s case, create a social-practice project. With this experience, I stepped back from the role of teacher and became more of a mentor and advisor. While this is a challenge, I find myself in those roles more and more, as students continually prove their ability to think critically about the world around them.