Installation view of the exhibition Solidarity Struggle Victory, September 13-November 9, 2019, at Southern Exposure, curated by PJ Gubatina Policarpio and featuring Jerome Reyes. Photo: Minoosh Zomorodinia for Southern Exposure. Image courtesy of Southern Exposure.

A conversation between PJ Gubatina Policarpio and Jerome Reyes.

This 2019 conversation took place in Jerome Reyes’s San Francisco studio and garden. Reyes lives between Seoul, South Korea, and his native San Francisco, and Policarpio recently moved back to San Francisco, with ongoing engagements on the East Coast. Policarpio is the curator of Solidarity Struggle Victory, and Reyes is one of the artists in the exhibition. Reyes’s studio holds key San Francisco State College (SFSC, now San Francisco State University) 1960s archives of student-designed curricula, which are central to the exhibition’s premise. In this conversation, both Policarpio and Reyes meditate on the larger implications of the show’s thesis in relation to time, pedagogy, movements, and camaraderie. This is the first installment of a two-part interview.

—PJ Gubatina Policarpio

Read “Reading at the Edge of the World: The Horizon Toward Which We Move (Part II).”

JEROME REYES: PJ, your description of the Solidarity Struggle Victory exhibition is immediately provocative: “A contemporary appraisal of one of the Bay Area’s most revolutionary contributions to the world: the right to learn about ourselves.” How did you arrive at this urgency? How is this premise both timely and untimely, given the roster of artists you selected and the overall cultural climate in the United States?

PJ GUBATINA POLICARPIO: In shaping this exhibition, I was influenced by my growing up in San Francisco, going to Balboa High School, and the Excelsior and Mission districts. The show reflects that education.

“One advantage of being an immigrant to this country is that you get to construct your understanding of what ‘Americanness’ is.”

My experience in San Francisco has always been embedded in relevant education. I read Toni Morrison in the ninth grade, followed by Carlos Bulosan, Sandra Cisneros, N. Scott Momaday, Leslie Marmon Silko, and others. These universe-opening voices taught me how to be in this new country that I was living in. You have to understand, I moved to the United States at 13, already armed with the knowledge of a whole world that I left behind. One advantage of being an immigrant to this country is that you get to construct your understanding of what “Americanness” is because it is not your birthright. You get to build it, shape it, and challenge it. In essence, Morrison and ethnic studies were my architects and foundation. They taught me everything I needed to learn about this country. They taught me about myself. This exhibition is a tribute to that.

At the same time, every revolutionary moment should have an appraisal, to remember the quiet moments that lead to historic events and to assess what is useful and what to discard from previous radical movements. It’s a balance between these twin impulses.

Installation view of Demian DinéYazhi, Untitled (Radical Indigenous Queer Feminist Bibliography), 2016. Mural is a part of Dene bāhī Naabaahii exhibition at the Center for Contemporary Native Art, Portland Art Museum. Photo: Demian DinéYazhi.

REYES: A majority of the artists featured in the exhibition are battle-tested educators and archivists, with invested practices in institutional building and breaking as well as self-reflexivity. Describe why you chose these artists, who take inspiration from San Francisco’s State College’s (SFSC) 1968 student strike, and how the exhibition’s purview welcomes a spectrum of viewership that is multigenerational and intersectional.

“Every revolutionary moment should have an appraisal, to remember the quiet moments that lead to historic events”

POLICARPIO: The artists in this exhibition not only have rigorous studio practices but also are engaged deeply with education and pedagogy. They are concerned with both teaching and unlearning. For example, you teach at Stanford and conduct other formal and informal work both here and in South Korea. Dylan Miner is a professor and the director of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at Michigan State University. Kameelah Janan Rasheed is a former high-school teacher who continues to work as a curriculum developer for New York City public schools. Outside of academia, the Oakland-based Dignidad Rebelde, a collaboration between the artists Melanie Cervantes and Jesus Barraza, and Demian DineYazhi’s collective, RISE: Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment, are critical platforms for visualizing, organizing, and disseminating strategies and aesthetics of survival and resistance through art, publications, and programming. Sadie Barnette and Patrick Martinez mine the visual and historical vernacular of their home cities, Oakland and Los Angeles, to transcribe and illustrate its complexity, nuance, and beauty. The artworks in this exhibition challenge us with new ways of seeing, understanding, and knowing. That’s radical education.

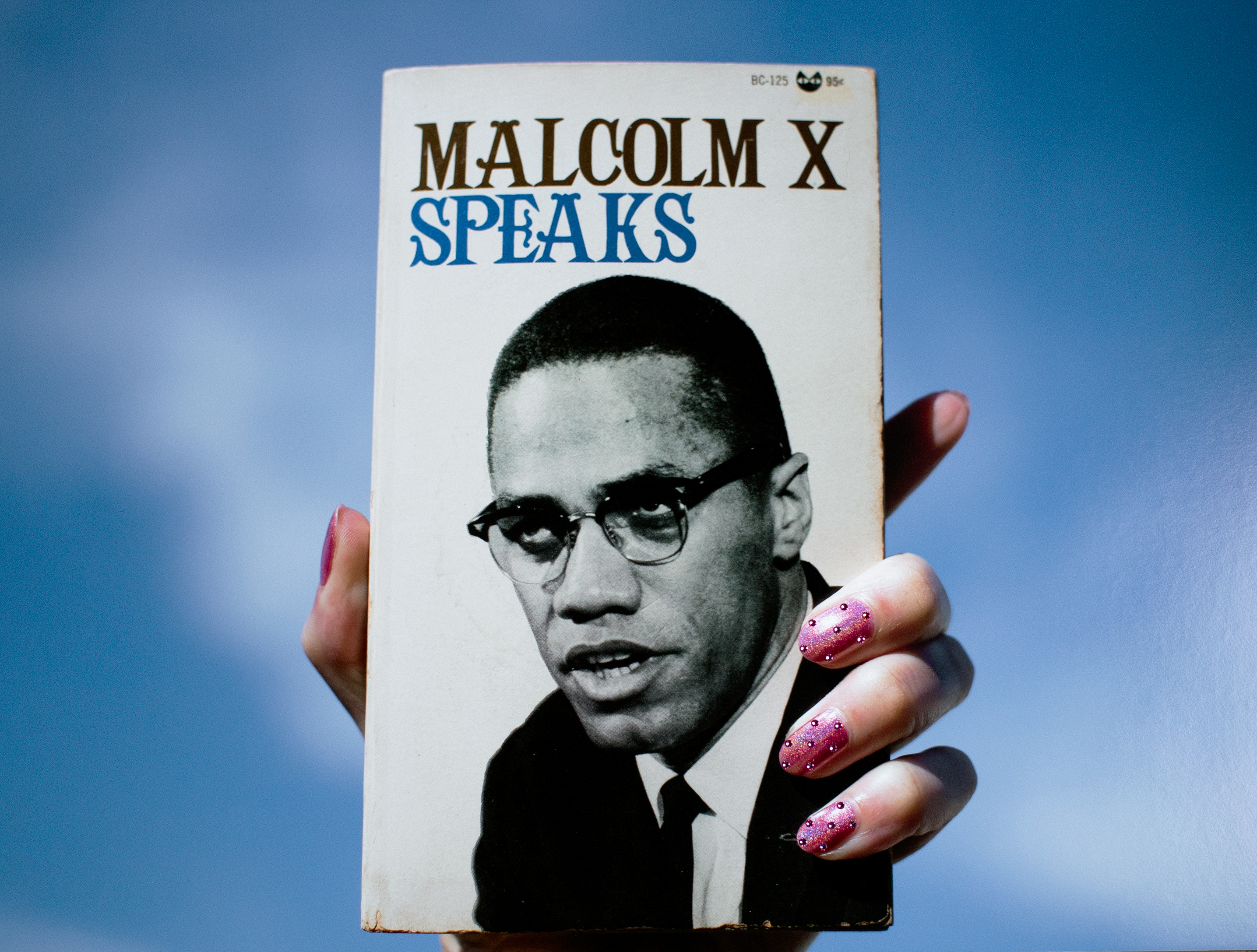

Sadie Barnette, Untitled (Malcolm X Speaks), 2018. Archival pigment print and Swarovski crystals. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles.

REYES: I was excited by the artist roster. The tone of the project framework takes a realist, pragmatic approach during the first term of Trump and a wave of leftist fiftieth anniversaries. How did you decide to approach this premise and, more importantly, how do you instill hope for all participants, viewers, and readers?

POLICARPIO: I initially wasn’t thinking about the Trump administration. For me, appraisal means critically thinking about what made this particular movement a victory. What were the tipping points? To me, the answer is solidarity: the bringing together of multiple struggles that are intertwined and interconnected, the intersectionality and the disruption of systems and institutions. As you know, this struggle came out of and after the civil-rights movement, the nonviolent protests and civil disobedience of that movement with the radicality and urgency of the Black Panthers, which originated in Oakland in 1966. It was all about active disruption, even about violence as a tactic and strategy. In revisiting this victory of 1968 and ’69, I want us to think about how a progressive, collective, and disruptive activism can be useful for us today. The exhibition presents a roster of artists born after 1969, who are all very much aligned with the ethos of the movement but also wrestle with and challenge its legacy, limitations, and future.

REYES: Your previous book, Textiles of the Philippines, has a global readership and is in the collection of the Thomas J. Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Solidarity Struggle Victory publication is central to your larger practice. Certain communities sometimes see literature as having a louder, more traceable lineage than in actuality strong contemporary/visual art lineages, like in Asian American history. You place this sensibility in multiple forms in the exhibition framework. How are you taking this experience, working with many authors to make a book that stands in tandem with the provocation of the exhibition?

POLICARPIO: I wanted to make a publication that could stand on its own. I didn’t want to just reproduce the exhibition and show artworks and list artists. I wanted a thoughtful parallel project. This led me to collaborate with Vivian Sming, of Sming Sming Books. I also worked with the Labor Archives and Research Center, at the J. Paul Leonard Library at San Francisco State University (SFSU), to include images and flyers from the era to emphasize the youth of the strikers. They were so young! To be a student at that time really meant fighting the good fight. I want the publication to sit in this context, which is not visible in the galleries.

“What does a college of ethnic studies look like today or in the future?”

I also wanted a multivocal text. I’m thrilled to have contributions from Tongo Eisen-Martin, the acclaimed San Francisco poet and educator, and Amy Sueyoshi, the current dean of the College of Ethnic Studies at SFSU, who will provide a historical overview of the need for ethnic studies, fifty years ago, and its contemporary concerns. What does a college of ethnic studies look like today or in the future? Books are something I live with; they open up worlds for me.

REYES: Speaking of publications, your extensive Pilipinx American Library (PAL) is a migratory, form-shifting project. Its most striking trait is that it pushes the legitimacy of multiple literary lineages and genres while welcoming a divergent range of audiences. Its momentum has even allowed you to write for the inflight magazine of Philippine Airlines and to work alongside numerous writers, such as Elaine Castillo, the author of the critically acclaimed novel, America Is Not in the Heart. How has PAL evolved?

POLICARPIO: PAL is my collaboration with a friend, Emmy Catedral. It grew out of numerous meals, walks, and conversations, usually on our way to meetings of Decolonize This Place, when it was headquartered at Artists Space in 2016. At the time, we both lived in Queens; Emmy is still in Jackson Heights. There was so much dissonance between where we were living—this polysyllabic, multilingual community that is one of the most diverse places in New York City, if not the world—versus a rhetoric that is so xenophobic and anti-immigrant; it was so jarring for us.

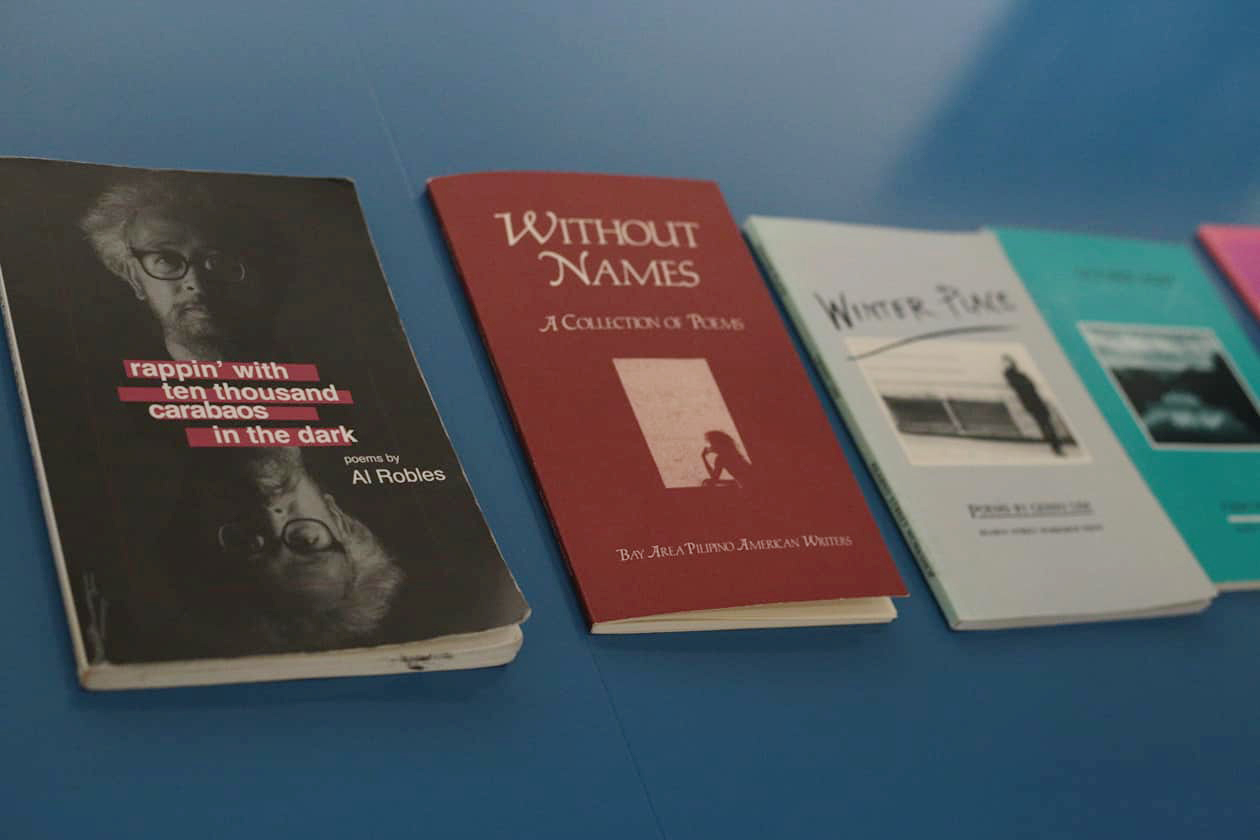

One of the ways we are able to assert our presence and history [in this country] is through books and literature. We were surprised to hear people within an educated art circle say, “I’ve never read work by a Filipino author before.” That was shocking for me, coming from San Francisco, so Emmy and I put our book collections together to create PAL. Since then we’ve been in exhibitions and residencies, at Wendy’s Subway in Brooklyn and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, with rigorous public-programming components. At the Asian Art Museum, our guiding words, “We dreamt of a place to gather,” came from the poet, oral historian, International Hotel activist, and San Francisco native Al Robles (1930–2009). With the San Francisco Public Library and Public Knowledge, a project of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, we hosted readings by Castillo, Janice Sapigao, Melissa Sipin, Malaka Gharib, Grace Talusan, and most recently Gina Apostol. With PAL, we want to amplify these voices and bring them to as wide an audience as possible. We are interested in creating nuance in countering historical erasure and invisibility: We are here. We’ve been here.

Installation view of Pilipinx American Library, Asian Art Museum, 2018. Al Robles, Rappin’ With Ten Thousand Carabaos in the Dark: Poems, 1996. Kearny Street Workshop publications: Without Names, (1985), Winter Place (1989), October Light (1987). Photo: Anthony Bongco.

REYES: You make so much of your work public, but what would you like to elaborate on, aspects of the work that viewers may not see as much but have equal importance?

“My practice is a confluence of sharing, oversharing, and intentional kinship.”

POLICARPIO: My practice is a confluence of sharing, oversharing, and intentional kinship. I feel so fortunate to not only be in conversation with but also actually have sincere connections with artists, scholars, curators, writers, and organizers who I admire and respect. These relationships manifest as mentorships, collaborations, and friendships, sustained equally over meals or coffee or long distance, over Instagram direct messages or emails. Part of nurturing relationships is providing critical feedback, including fashion advice, and equally citing and hyping their work; we’re proficient in both. These friendships, especially in this field, can be revolutionary and should be celebrated.

Read “Reading at the Edge of the World: The Horizon Toward Which We Move (Part II).”