Joulia Strauss at MYLIVINGROOM studio in Athens, Greece

It would be an oversimplification to introduce Joulia Strauss to you as a Russian visual artist who lives and works in Berlin, Germany. Joulia is a Mari, from the Mari El Republic located in the eastern part of the East European plain of the Russian Federation, along the Volga River, right where the Ural Mountains begin. This small community of approximately 600,000 people has a rich tradition in the performing arts, and Joulia grew up in the middle of this, with two of her family members at the helm of the Mari National Theater in Yoshkar-Ola.

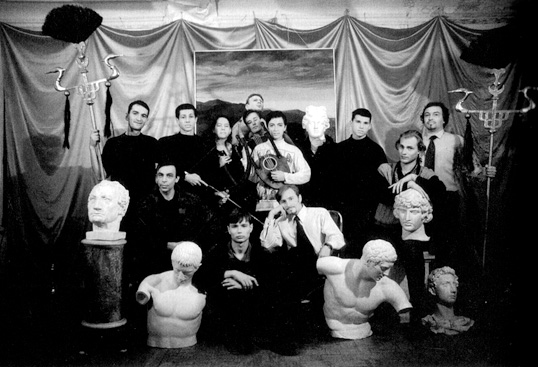

She got an admirable start in the art world by studying at the Platonic New Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg (founded in 1989), alongside artist and founder Timur Petrovich Novikov. This evolved into the Neo-Academism art movement in the 1990s. In my discussion with Joulia, you’ll see how she entered into the exclusively all-male New Academy, finding herself at the heart of the intellectual elite and queer culture of St. Petersburg at the time.

Classically trained as a sculptor, she creates works reminiscent of an antique and neo-classical idealism, always aiming for harmony, perfection, and beauty with a contemporary twist. She continued to be a member of Neo-Academism when she decided to pursue a fine arts degree at the University of Berlin. Being a skilled craftsman on her own, Joulia soon became fascinated with technology, science, and mathematics. By finding a lot of her answers in science (with the help of prominent thinkers in Berlin), her work began achieving the rigor for which she strove. She founded an artist-run space called art_science for gatherings of critics, scientists, artists, philosophers, in order to enable vital exchange outside of their own networks.

Joulia is highly politicized and conscious of the changes our society is undergoing. The sight of last December’s riots in Greece all over the media literally shook her. Joulia’s deep love and appreciation for ancient and contemporary Greece inspired her to come to Athens on a residency at MYLIVINGROOM in Metaxourgio, to observe and begin decoding the active role of artists in contemporary Greece.

Having taken September off, I am very pleased to return to my column and to you with this Joulia Strauss interview.

Georgia Kotretsos: I am interested in discussing your upbringing as a Mari pagan within a traditional community. What role, if any, did belief play in your life at school as a child? How did Orthodox Christianity and Mari paganism mix in the Soviet Union?

Joulia Strauss: Communist indoctrination served as the dominant set of beliefs for all in the schools of the Soviet Union. I wasn’t discriminated against per se, but the fact I was a Mari pagan was never addressed by schoolteachers. I wasn’t given the silent treatment, but being a Mari served more as an intimidating territory for them.

On the other hand, Maris’ animal sacrificial rituals and practices were marginalized and disguised to appear to the general public as folksy music festivals of the Mari El Republic. Mari people were kept on a tight rein. That did not stop my grandmother, Anastasia Strausova, and mother, Sarra Kirillova, from significantly contributing towards the establishment and growth of the Mari National Theatre in Yoshkar-Ola. They were actresses; on top of that, my mother was the National Theatre’s director, yet both were custodians of the Mari people’s heritage and pagan faith. I am the third generation of Mari witches nourished to resist political, cultural, and religious oppression by the state.

The Volga is the Mecca of spiritual healers, occultists, mysticists, diviners, sorcerers, witches, and enchanters in Russia. It is a highly charged land and the members of the Mari minority are bold despite the fact they are continuously mistreated because they are practitioners of a faith other than Christianity.

GK: In 1993, in order to enter the New Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, you pretended to be a young boy by shaving your head. How long did this “performance” last and why wouldn’t you enter as young woman?

JS: Our director and founder, Timur, figured what was happening right away, and he appreciated the gesture greatly. The New Academy tried to be even more reactionary than the State Academy of Arts in Russia at the time, by referring straight to the roots of academia: no women. I liked the voluptuous, elitist, and austere queer conservatism. Can you imagine working on Greek busts being surrounded by beautiful men? It was certainly a high-point initiation into the arts. Girls behaved like groupies at that time, and so I performed a non-femaleness – kind of a Marc-Almondness.

GK: What role did Neo-Academism play in the 90s in St. Petersburg, and what does it mean to you today to have been traditionally trained as an artist/sculptor/craftsman/member of a movement/intellectual with a pre-Perestroikan idealism? How did you make the transition from being identified as a member of a school of thought to an independent artist, in the Western sense and model?

JS: Neo-Academism can be discussed as a Western model as well. It was a movement, which was created to answer the question Western institutions had about Eastern art at the time of Perestroika. Our answer was beauty. We rejected freedom of expression and contemporary fads by fully dedicated ourselves to a classical mode and tradition.

New Academy of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, 1996. Joulia is in the center holding a lyre.

This model served its purpose. We had shows in museums and exhibitions spaces that were of key importance to us and the art world at the time, such as: Self Identification, Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo and Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, 1994; Metaphern der Entrücktsein, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, 1996; Kabinet, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1997; Between Earth and Heaven, Oostende Museum of Modern Art, 2001; The Greek Classic Idea or Reality, Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, 2002 and elsewhere. Neo-Academism got a lot of attention very soon.

Being the only female student at the New Academy, with Timur’s support literally overnight, I gained stardom fame in Russia among the art community. I was exclusively identified with Neo-Academism, which was a one-way street creatively because I was bound to produce within the limits of the movement.

In 1995, I decided to leave St. Petersburg to attempt to pursue art independently. In my opinion, Neo-Academism hit a wall soon after. The popularity, the hipness, and the IT factor made us (meaning the members of the group) rely on repetition. It took me quite a while to detach from the safe, well-functioning Russian art path and learn to create within my own context. Up until 2000, I was still involved in projects of the New Academy. I did not become an independent artist overnight, but rather I switched schools of thought, from Plato to Pythagoras.

GK: Some artists are lucky enough to meet that one great mentor that nurtures their passion and vision, but I hear you were fortunate enough to have met three great male figures. Please tell me how your work evolved, as your mentors changed from Timur Petrovich Novikov (1958-2002) to Georg Baselitz, and finally to Friedrich Kittler.

JS: Timur has been a cultural advocate, a diplomat, a creative commando for the arts in Russia. He was very successful on his own before he founded the New Academy of Fine Arts in 1989. Within a homey luxurious setting, with over-the-top drapes, literally at the garden of delight of queer culture, surrounded by beautiful men, sculptures, and ideas, Timur taught us how to live and work intensely. My first exhibition, entitled Sculpture in the Beginning of the 21st Century, took place at the St. Petersburg Summer Garden. This is where Peter the Great installed statues under the trees so that “people could learn from their faces,” as he once put it. I exhibited busts of the students of the New Academy, as well as Timur, in a circle. These sculptures looked as if they had always been there. It was mind-blowing at the time to view the busts in the presence of the actual models during the exhibition. And for me, it was not only a classical gesture, but also a comment on how our lives were structured at that time. I literally saw us like characters from antiquity that lived in the 90s. The romanticism of our ideals was highly charged when we worked and lived together. We gained knowledge during our walks at the Academia. Timur would tell me that I have Apollonian eyes.

At his peak he lost his eyesight, yet he continued to lecture at the Academy and work on his projects. During that period, I made a bronze sculpture of him with diamond eyes. Surrounded by beauty until the end, he passed away, leaving all of us behind. Unfortunately, AIDS got the best of him.

In 1997, I decided to enroll to the Berlin University of Arts to continue growing as an artist. Although my German was poor, I had to pick my advisors right away. It was during one of those early days at the Academy when I was walking down a corridor and came across a bald man shouting very loudly in German at a young girl who was crying and surrounded by a big group of students, “Where is your head? Where is your intelligence?” I didn’t know who he was at the time, but I knew right away I wanted to work with him. Of course I am talking about Georg Baselitz. I applied for his class right away.

Joulia Strauss and Georg Baselitz, Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, 1999.

For five years, we had an exciting, stimulating hardcore discussion about art. In 1997 I did a very challenging project, entitled 12 Caesars of the Techno Empire:

Joulia Strauss, "Twelve Caesars of the Techno Empire," at E-Werk, Berlin, 1997.

Twelve busts of Berlin DJs were portrayed as Greek gods. The project received wide media coverage in Germany and abroad. I believe techno music was the first positive German cultural phenomenon after World War II that was connected to the neo-academic idea of beauty.

Soon I became interested in making sculptures by exploring the latest 3D technology. I was the first artist in Germany to run around with a pioneering transportable 3D scanner and think about the mathematical perfection of ancient Greek statues, which I could now begin examining from the inside.

By literally scanning significant Berlin figures with a 3D scanner, I met mentor number 3: Friedrich Kittler, the Dracula of German Media Theory. He stood between the tradition of Foucault, Lacan, and Heidegger. Kittler explored the existential dimension of computers philosophically. We once met at the Paris Bar, which was considered the art bar at the time in Charlottenburg, Berlin, where after a few drinks we confessed to each other that we are Greeks at heart and what we are interested in beauty. Our philhellenic beings found each other through technology, and that was the beginning of a lasting collaboration.

The 3D animation, Virtual Kingdom of Beauty, showcased culturally active Berliners painting an accurate picture of the cultural German landscape in 45 minutes. Part two of the animation was the numerically-cast bronze portraits, which were exhibited at the Pergamon Museum, a site that is rarely opens its doors to contemporary art. By doing so, I connected Greece with the visual language of our generation. Holographic projections over the ruins looked so natural that I felt like an ancient Greek artist who was born in our age by mistake, but now uses technology to achieve just about the same level of excellence…

GK: You participated in the 2009 Athens Biennial. Tell me about the work you showed here and the preparation that went into it.

JS: I was invited by curator Diana Baldon to participate in a show entitled, For the Straight Way Is Lost, at the second Athens Biennial, Heaven. She is familiar with my work and finds its qualities culturally engaging for contemporary Greece. Diana has seen my work evolve over the years.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=58Z9RFxJ1B8]

The video First Delphic Hymn to Apollon navigates through a fairy-like landscape compiled out of actual views of Delphi. It is part of a larger umbrella project I have been developing in collaboration with music scientist and media philosopher Martin Carlé over the last few years, called Cat-Notation. Reconstructed fragments of music notation excavated in Delphi were translated into a set of 3D sculptures, which embody mathematical operations as animals. We have used the interval ratios of different ancient modes of music as proportions for these synthetic sculptures. The limbs of their bodies move according to the melodic progression, unveiling specific characters and ethical qualities of the seven modes of archaic music. Animals morph into one another and display the little-known phenomenon of modulation, the transition between different scales. Cat-Notation provides a sculptural system for experiencing the reliable laws of beauty that exist in the concurrence of music, mathematics, and time.

In the case of the First Delphic Hymn of Apollon, when listening to the melody reconstructed after ancient fragments found in the area, the viewer encounters animals proportioned after Pythagorean harmonic tunes. The hymn was further developed and written by Athenaios in 138 BC to show the beauty of Greek music to the Romans. It culminates in a dance of the so-called all-embracing Dorian Sum-Cat. This video was made with legendary 3D artist Moritz Mattern.

For the needs of the Cat-Notation, Martin Carlé and I caught a turtle and killed it for its shell at Pontus, at the southern coast of the Black Sea, to build the lyre you see me playing in the video. We tuned it according to Martin’s computer reconstructions of the Ancient Greek modes of music. As I was singing the hymns without any difficulties, thanks to the vocal alphabet and my Cyrillic background, I was just one step away from attempting to play the instrument.

Our lecture-performances have been presented at the Tate Modern, at ZKM in Karlsruhe, and next year, we have been invited to perform at the exciting archaeological site of the Temple of Artemis Orthia in Messinia, Peloponnese, in our beloved Greece.

Joulia Strauss performing the "First Hymn to Apollon," Tate Modern, London, June 29, 2008.

GK: When we met the other day at Metaxourgio, you mentioned that you usually work in enormous project spaces in Berlin, while you’re currently working at a modest-sized studio in downtown Athens. When I began talking about this contrast out loud, you emphatically said, “My studio is here, in the streets, among the people, in Omonia Square.” What are your studio needs, generally speaking?

JS: My colleague Martina Schumacher and I currently occupy a 420 square meter (4520 square feet) studio on the 6th floor of the Ullsteinhaus building, the first concrete building in Kreuzberg, near the Templholf airport in Berlin. It used to be the Ullstein Publishing house. It is a great space to work in. Greek artist Dimitris Tzamouranis recently joined us as well.

Joulia Strauss's studio at the Ullsteinhaus building in Berlin.

Generally speaking, my studios have always been pretty big because they are often exhibition or project spaces, where artists exhibit their work without institutional bureaucracy. Martina and I have also approached corporate building managers in the past to negotiate our studio needs for little or no cost.

Joulia Stauss's previous studio space.

GK: What kind of project are you’re working on right now in Athens, if your studio needs no walls? How do you perceive Greek contemporary art?

JS: Since I choose to live and work here for the time being, I consider myself a contemporary Greek artist.

I have a deep and abiding belief in Greek potential. Speaking to many young artists, art historians, and activists, I could observe that they still have amazing handicrafts, which enables them to establish the new and healthy notion of the “work of art,” in contrast to industrially-fabricated luxury objects, which no longer have anything to do with fine arts; people here have no gap between the past and the present. Their cultural memory entails the gods; they operate with those in everyday conversations. These people have seen the world and came back.

As we speak, I am an artist-in-residence at MYLIVINGROOM, a unique word-of-mouth Athens residency program, which is run by art historian and curator Sotirios Bahtsetzis. I’m very happy to be able to work on a sculpture, which embodies the structure of modulation (changing from one tune to the other) of the Second Delphic Hymn to Apollon.

Joulia Strauss at MYLIVINGROOM studio, Metaxourgio, Athens

GK: Please, describe Omonia Square through your eyes. It will help me understand your fascination with that part of our city.

JS: Omonia, in downtown Athens, epitomizes for me the despair of the junkies and the deadlocks of Iraqi and Afghan immigrants. They escape death day-by-day, and there isn’t any chance of integration in their future.

The tragedy of junkies of Omonia provides me with a very clear picture. The picture narrates, “this is the end of a particular political and economic model of the world!” So I’m here for the cultural revolution.

And that’s a wrap!