For any fiending New York City art and culture aficionado, renting an automobile and driving up to The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art to see Michael Ashkin’s recently installed exhibition is a perfect weekend getaway. The museum itself, designed by I.M. Pei, sits on the northwest corner of the main Cornell University’s campus in Ithaca. Walking around on campus, your peripheral vision becomes excited by the architecture of this museum and other impressive buildings.

Michael Ashkin, "Untitled (where each new sunrise promises only the continuation of yesterday) (an abridged title, the first of twenty-one lines)," 2009. Recycled cardboard, 75’ x 6.5’ x 3 inches, installation at Sculpture Center, NY.

Ashkin’s prolific interconnectivity in photography, writing, video, and sculptural installation informs and references actual geographic spaces. My initial reactions to his elegant installations of ephemeral urban and suburban landscapes was a shift of focus to my vision that occurs outside the very center — less of sight than of thought. Ashkin has created a universe of peripheral visions, allowing people to only focus on the sidelines, however hard they try to focus on the center. Researching the margins of urban city lines and territories of the contemporary American landscape, Ashkin asks his viewers “to sustain a look at these zones for longer than (your) attention might allow” (Anthony Graves). In exercising this type of mediation, all I can really see after a while is the essence of color and shape. When you look into Ashkin’s work, most of the desaturated bedouin color palettes and expansive yet portable cities support my prior experiences of sustaining the look.

Michael Ashkin, "Untitled (where each new sunrise promises only the continuation of yesterday) (an abridged title, the first of twenty-one lines)," 2009. 548" x 244" x 3 inches, cardboard, installation at Secession, Austria.

Michael Ashkin, "Adjnabistan" (detail), 2005. Recycled cardboard, gypsum, glue, 46 x 132 x 252 inches.

Michael Ashkin, detail from "Hiding places are many, escape only one," 2007-2008. Cardboard, dimensions variable.

On view in four adjacent galleries from April 3 – July 11, Michael Ashkin was curated by Andrea Inselmann at the Johnson Museum at Cornell University, NY. Ashkin shares 20 years of dedicated work with a reiteration of a large-scale cardboard city from Untitled (where each new sunrise promises only the continuation of yesterday) [an abridged title, the first of twenty-one lines] (2008-2010), which he showed last year at Secession in Vienna, expanding on ideas of logic in urban spatial organization.

Also on view, 10 digital prints from Ashkin’s photographic series Long Branch (2002-2010) seem at first glance to be documentary photographs of the New Jersey beach neighborhood that has been embroiled in a fight over eminent domain abuses for over a decade.

Two videos are included in this exhibition and, as Andrea Inselmann quoted during the installation process,

“One video is projected in a darkened gallery and the other one on the facade of the Museum. Presenting the desert as a habitat, a threat, but also as a spiritual experience, Here, 2009, functions as a counterpart to the untitled cardboard sculpture in this way. Just as the installation is a site for viewers to think about space, the video, which combines the visual representation of an empty room with a rhythmic, even poetic, voice-over by the artist. This provides both actual and metaphorical space for internalization and projection. Projected at about 20 x 35 feet onto the facade of the Museum, Ashkin’s video Centralia, also 2009, takes its name from the mining town in central Pennsylvania, where coal deposits beneath the town caught fire in 1962, have been burning since, and will probably continue to burn for another hundred years. But rather than document the by now nearly abandoned mining town, Ashkin directs our attention to an ongoing mining operation nearby, again foregrounding layers of absence in the process of history.”

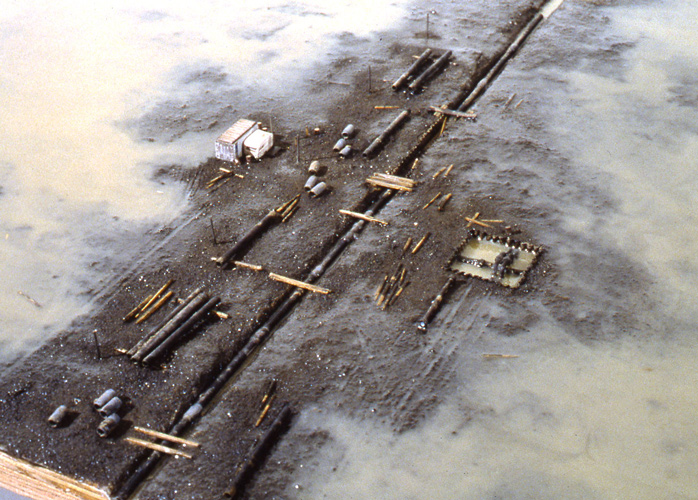

In addition to these recent works, Ashkin shares his well-known miniature scale models from the 1990s depicting marginalized landscapes. These maquettes strike me as oddly perceptive, as one can say there is a genre of artists now incorporating the aesthetics of Google satellite image searches. Ashkin’s labored installations have given us this aerial precision well before our personal hand-held devices.

Michael Ashkin, "No. 104," 1999. Wood, metal, dirt, glue, resin, plastic, paint, 33 x 38 x 72 inches.

The quiet of Ashkin’s pieces ask us to pay attention to our peripheral vision and be present with them, consequently forcing us to be quiet with ourselves for longer than is comfortable. In this sense, these freeze frames of landscape narratives also become personal ones, as we can all relate to the indelible act of marginalized landscapes.