We tend to spend a lot of time talking about art in terms of “work” nowadays, but we don’t always consider how important respite and retreat can be when it comes to sustaining an artmaking practice. Artists, like all creative individuals, seek retreat for different reasons: to increase their focus and resolve; to problem-solve or brainstorm; to find new inspiration in unfamiliar surroundings; and to make new friends and and share ideas with other people. For the past 100 years, artists living in the Midwest and beyond have decamped for the Ox-Bow School of Art, located in the town of Saugutuck in Southwestern Michigan. Ox-Bow provides a unique kind of retreat that’s part art school, part summer camp, and part bohemian artist’s colony. Its idyllic 115-acre campus includes forest areas, dunes, a lagoon, and a number of charming older buildings, some of which are still used as dormitories. This summer marks Ox-Bow’s centennial. In celebration of this event, the Chicago galleries Corbett vs. Dempsey and Roots and Culture have collaborated with Ox-Bow on a joint presentation of artworks by current and former students, teachers, and staff. (The Grand Rapids Art Museum in Michigan is also featuring an exhibition of works by Ox-Bow artists as part of these Centennial events).

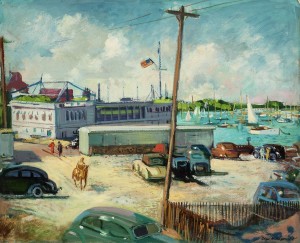

Ox-Bow was founded in 1910 by Frederick Fursman and Walter Marshall Clute, two Chicago artists who taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, with which Ox-Bow has long been affiliated. Fursman and Clute wanted to provide artists with a reason to escape the city, and began holding art classes for their students and other artists each summer in Saugatuck, Michigan, which lies along the Kalamazoo River about 142 miles away from Chicago. At first, classes were held on a farm on the east bank of the Kalamazoo River about a mile upstream from Ox-Bow’s current location. In 1914, classes moved to the Riverside Hotel, a small inn founded by the Shriver family that soon became known as the Ox-Bow Inn. Originally built on an ox-bow-shaped bend of the Kalamazoo River, the Riverside hotel had been cut off from patrons ever since the river channel was straightened to flow directly into Lake Michigan, which dashed Saugatuck’s hopes of becoming a major Great Lakes port. Faced with a shrinking clientele, the Shrivers decided to lease the building to a group of artists for an entire summer. As Ox-Bow took on a stronger identity as a school of art over the years, Saugatuck, too, began to reinvent itself as a Midwestern resort community and artists’ enclave. Today it is known in the region as the self-proclaimed “Art Coast of Michigan.”

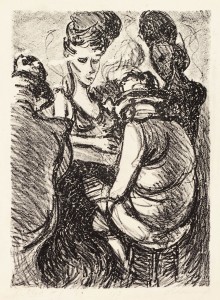

Issues of civic branding aside, Ox-Bow’s importance to the Midwestern art community over the past century has been immense. The Ox-Bow school, says John Corbett, co-owner of Corbett vs. Dempsey, “has served as a sort of seed bed, a Utopian sanctuary for Chicago artists, replenishing them, re-connecting them with the natural environment, allowing them to experiment quite widely with unfamiliar media. If you consider the range of alums, Ox-Bow has been an important place not just to Chicago but to the American art scene in general.” Corbett and gallery co-founder Jim Dempsey were approached by the Ox-Bow Centennial committee several years ago with the idea of the gallery curating a show focused on the history of Ox-Bow. Corbett vs. Dempsey specializes in the work of Chicago artists and the post-1940 history of art in this region, making this gallery an ideal space to showcase work by Ox-Bow founder Fursman along with artists Albert Krebiel, Edgar Rupprecht, and Isobel Steele MacKinnon–all early supporters of Ox-Bow. The show also includes works by Francis Chapin, Eleanor Coen, Max Kahn, Ellen Lanyon, Miyoko Ito, Seymour Rosofsky, Margo Hoff, Peter Brötzman, Christina Ramberg, and others. There is also a small, very early lithograph by Claes Oldenburg on view behind the reception desk, made by the artist in the early 1950s when he was a student at Ox-Bow.

Several of the works on view at Corbett vs. Dempsey depict the small, simply appointed rooms that artists call home during their summer stays at Ox-Bow. Miyoko Ito’s lithograph My Room at Ox-Bow shows a room with a twin bed, a small desk and lamp, and a window flung open to the view outside. Margo Hoff’s Untitled (Ox-Bow Interior), c. 1945, shows a similarly spare little chamber that includes an unmade iron bed, a simple wicker chair and cushion, and a bottle of wine on an otherwise empty shelf. Here, too, an open window expands the pictorial view to the grounds outside. Both artists depict their rooms as spaces of solitary refuge that nevertheless remain open to community and the outside world. Max Kahn’s watercolor painting of several figures standing on a dock conveys a related idea: the figures in his painting are standing in proximity to one another, but they’re staring off in different directions, lost in their own private thoughts. The work of these artists suggest that at Ox-Bow, the artists’ retreat can be a space of private musing or of group conviviality. Whether it’s the former or the latter can change from moment to moment, depending on the individual’s frame of mind.

Today, the Ox-Bow experience combines intense study with good old-fashioned goofing off. Classes meet from 10am to 5pm each day, with dinner served at 6pm. Afterward, there’s plenty of opportunity for recreation and hanging out, to swim and canoe, play volleyball, or dance around evening campfires. Ox-Bow is famous for its costume parties (as well as for the copious fleas, ticks, mosquitoes and spiders that often plague its residents). The experience of living and working with other people in this type of close, grimy proximity can be exhausting as well as exhilarating (for a more personal take on the Ox-Bow experience, check out the online blog of Chicago artist Susan Kwon, whose journal entries detail her experiences at Ox-Bow and its impact on her work). Few come away feeling the experience wasn’t 100% worth it. Earlier this month, the LeRoy Neiman Foundation announced that it was giving a $1 million dollar gift to Ox-Bow and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which now administers Ox-Bow, in honor of the latter’s 100th anniversary. The money will be used to fund scholarships and to support Ox-Bow’s fellowship program.

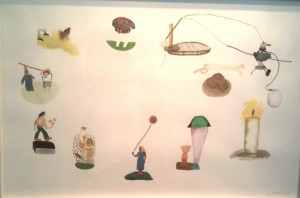

For the Ox-Bow Centennial Committee, coming up with a venue to showcase works from the younger Ox-Bow generation was a no-brainer: Eric May, who’s worked as head chef at Ox-Bow for the past 10 years, also happens to run the highly regarded contemporary art space Roots & Culture, which is just a few minutes walk from Corbett vs. Dempsey. In a 2006 interview with the website Center Stage Chicago, May noted that “at Ox-Bow, artists work together and live together as a community; it’s sort of an updated commune environment.” In Roots & Culture’s Ox-Bow show, the paintings, drawings, photographs and mixed-media installations tend to emphasize these types of communal social interactions over contemplative isolation. Carmen Price (who works alongside Mays in the Ox-Bow kitchen) submitted a gouache drawing titled Explore Your World, from 2006, which depicts a quirky circle of people, objects, and activities of the sort one might encounter at Ox-Bow. Nate Wolf’s oil painting Trouble, 2006, shows the sprawling activities of a mass of people; it could be the scene of a riot, a festival, or a giant playground for grown-ups. The inclusion of Mike Andrews‘s 2010 yarn tapestry provides a humorous nod to the lanyard and macrame handcrafts associated with summer camp art (it’s also a terrific example of this artist’s boldly colorful works, which combine handicraft and high Abstraction to truly loopy effect). Aspen Mays’s untitled photograph was made from the glowing bodies of fireflies trapped inside her camera. The insects’ bodies provided the light that exposed the film during a one minute period on a summer night at Ox-Bow (Mays released the fireflies once the roll was exposed).

Aspen Mays, "Untitled (fireflies inside body of my camera, 8:37-8:39pm, June 26, 2008)." Archival inkjet print.

The exhibition at Roots and Culture also includes the original kitchen stove and other appliances used at Ox-Bow, which were dismantled after the kitchen was updated in 2006 so that a winter session could be added. Although the stove is now a permanent part of Roots & Culture’s kitchen area, six Ox-Bow cooks, all of whom are artists, have amplified its significance by creating an art installation around it that “conjures the spirit of the Ox-Bow kitchen.” The resulting environment provides a fittingly unpretentious metaphor for sustenance, and a tribute to those unique forms of nourishment that only a place like Ox-Bow can provide.

Pingback: Bad at Sports on Art:21 blog: Summers at Ox-Bow : Bad at Sports

Pingback: Centerfield | Fielding Practice Podcast Episode #10 | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Centerfield | Fielding Practice Podcast #13: “Feast” (or Famine?) | Art21 Blog