“Philip IV” and “Mariana of Austria” shoot the breeze in the Prado. Period costume memo not picked up by majority of attendees

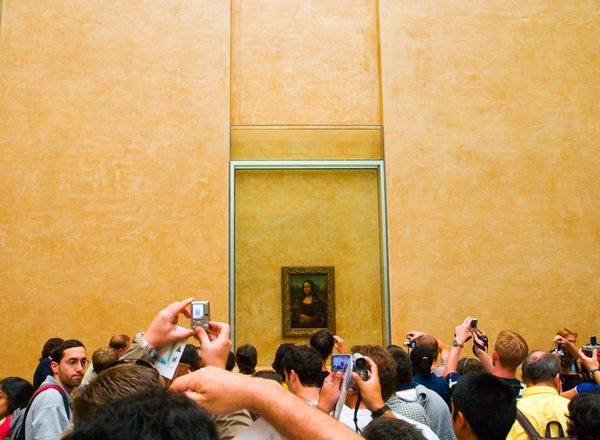

On a single day this week I saw a clutch of paintings that would, by most reckonings, be referred to as “masterpieces”: Velazquez’ Las Meninas (1656), Goya’s Third of May 1808 (1814), Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1503-4), and Picasso’s Guernica (1937). I’m deliberately not linking to images of them, because you already know what they look like. Perhaps the images flicked into your mind on reading the titles. I thought I knew them too, but this prior knowledge made it almost impossible to look at the real object with any kind of immediacy. Anecdotal historical information, the stuff upon which wall labels and guided tours are built, deadens an immediate response to a work of art. It thickens the air; it slows down your reactions. This distancing from the physicality of the thing in front of you is made literal in the Louvre’s disastrous hang of the Mona Lisa, pinioned behind glass like an entomological specimen: dead.

The sort of contextual historical knowledge used to accompany a reproduction of a famous work like Las Meninas in an historical textbook seems pretty useless when employed in front of the actual object. The object can’t be explained away that easily, and the painting looks back, amused; both Las Meninas and the Mona Lisa seem, in their focal wry female smiles, to play out this bemusement themselves. Language swarms around the smiling object and most museum hangs and curatorial approaches — burdened with words: written, read, said — reduce the duration of actual looking. We talk because we don’t know how to look.

Larry David explains the Met's latest acquisition, Degas’ “The Little Dancer,” to the board of trustees.

I’ve lost count — actually, I wasn’t counting, I was digging my nails into the palms of my hands while smiling politely — of the number of museum professionals who have decried the amount of time the “general public” spend in front of works of art in museums. Five seconds, six seconds. They’re horrified. I never know what to say. What I’m thinking is: so how much time do you spend looking at works of art in museums? Have you ever been to a Biennial? (Bring a stopwatch next time). Plus: so how much time are you supposed to spend looking at works of art in museums? I admit that, with the exception of works of art I regularly lecture in front of (and then I’m not strictly looking at the work, I’m trying to count the suppressed yawns in the audience; it’s the quivering jaws), I’ve spent far more time looking at reproductions of works of art than actual works of art. And I think those experiences are perhaps as important as any I’ve had with original works of art.

I do think that our relationship with reproductions of works of art is of a different and perhaps more profound calibre than our relationship with the real object. A mousepad or screensaver or postcard/bookmark finds an insidious foothold in the mind far more easily than a one-off encounter, among crowds, in the heat, with a tiny audioguide raining in your ear. I can’t extricate Moby-Dick from a postcard of an Eva Hesse ink drawing for this reason; somehow, illogically, magically, they intertwined for the month-or-so duration of my reading, and I feel that I know the Hesse better for it. But the difference between reproduction and real (excepting photographs, which, for the most part, you might as well look at in reproduction anyway) is almost always that the object itself is stranger, coarser, more variable and less compliant than the text-nested image in a book or on a website. Reproductions (God, I’m trying hard not to mention Walter Benjamin) neaten things up into digestible nuggets; why else is the immediate reaction on seeing the Mona Lisa to photograph it? Oh, I’m photographing the audience photographing it, ha-ha, I claim, postmodernly, but really I’m photographing it, because I’m no less in thrall to its weird power than they are.

The 'Mona Lisa': your looks are laughable, excessively photographable, yet you're my favourite work of art

The messy, untamed quality of the original work of art can defeat comprehension in a way that snaps you back to why you like art in the first place. Looking at Guernica this week — a painting whose standard reading, as a polemic against the horrors of war, I’ve always found rather dubious, given both its author and its form — I was struck by its absolute transformation in reality. The real object, streaked with blobs of birdshitty paint, scuffed and scrubbed in broad patches like a mistreated saucepan, is more complicated and far less compliantly about something than the textual rationale might have you believe. I have no idea what Guernica is really about — certainly not Guernica — and that’s made me actually start to enjoy it. Really, it’s the pleasure of the absolute strangeness of the object — which is neither “appreciation” nor comprehension, really, but instead an exhilarating abandonment of the safety net of rational understanding — that provides the kicks you’re looking for.

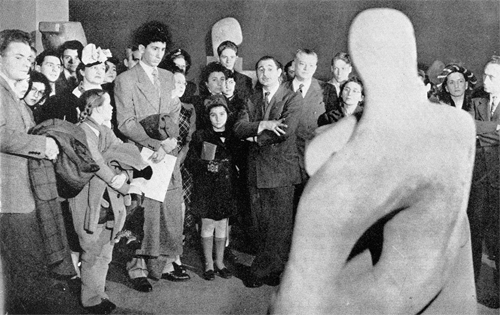

“Exhilarating kicks” at MoMA in the roaring forties. Photo by Nancy Bulkeley. Cover of “The Questioning Public,” a bulletin produced by The Museum of Modern Art. Fall 1947, Issue 1, Vol. XV