When I visit an exhibition for the first time, my attention is foremost on the work and how it has been curated. Soon after, I come to think about its peripheral framing, or how this exhibition fits into its broader surroundings. I blame this on my vocation as a radio host of arts segments. At work, I have to produce programming for a specific target audience while also being responsible for providing context for potential regional listeners too. When I report on the arts, I do extensive research combing through a multitude of stories; this leads to interviewing artists, musicians, and filmmakers, and finally editing segments before I select the most interesting stories worthy for broadcast to the public. Is curating similar in some ways? On a smaller scale, in my independent curating projects, I see parallels between my radio work and selecting art for a specific space. It leads me to wonder how ideas about exhibiting art trickle down to a broader museum-going public, one that may not necessarily have an art critique background.

One such way is when curators take on the responsibility of translating an exhibition for a local audience by interpreting its significance through “home grown” parallels of political and historical experiences that resonate locally. So when Vancouver Art Gallery launched the first Canadian solo exhibit of Art21 artist Kerry James Marshall, I was curious to see how the curators (director Kathleen S. Bartels and artist Jeff Wall) might relate the show to Vancouverites, people whose city has a relatively very small black population. Marshall himself shared his awareness of this fact in a recent interview with the Globe and Mail, citing that there are very few black-identifying artists getting attention in Vancouver. Of course, it is important that locals understand the significance of Marshall’s profound work completely on its own merit, but I wonder if Bartels and Wall could have ventured to tie the exhibition in with Vancouver’s uniquely diverse ethnic population.

I won’t go so far as to suggest what Bartels and Wall could have considered adding to their already fine show. It is a well-known fact that curators often deal with incredible limitations in putting together exhibitions, especially of this magnitude. However, the creative and ambitious proactivity of so many curators today to help draw surprising and interesting local connections is exciting. It’s a way for an incredible survey of works, like Marshall’s, to really live differently, breathing new life into each environment beyond the gallery’s walls.

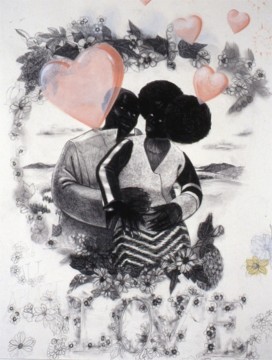

Marshall’s paintings examine the black experience in America. His approach pushes the idea of an unfulfilled utopia that envisions scenes from private spheres of black life enacted in public. By painting intimate scenes taking place in domestic settings (backyards, living rooms, etc.), Marshall’s work avoids clichés of Blaxploitation or predictable kitsch. As Marshall states in his Art21 segment, he rethinks pictoral representation with black figures — frolicking at the beach, lounging at picnics, boating – taking part in activities suggesting leisure time and dispensable income.

That Marshall’s figures are absolutely black is an aesthetic choice whose defense he has come to in interviews, insisting on the beautiful depth of color that black paint provides in creating the figure/ground distinction. This is important symbolically; the actual blackness of the subjects is discomforting and even disquieting as it plainly confronts the representation of blacks in pictorial space and in historical popular culture. Black here is a disassociation, an abstraction from blackness that turns figures in Marshall’s paintings into ideas of “something-other-than-us,” rather than people. The abstraction is advanced by collage work that acts, at times, as defacement.

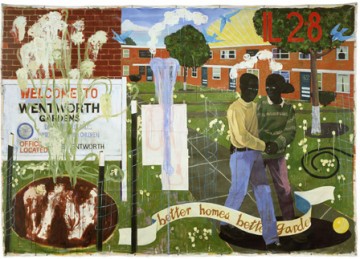

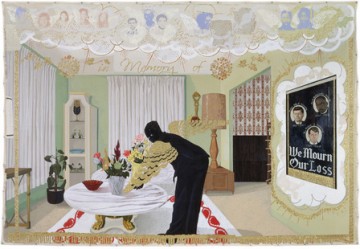

Some of Marshall’s most iconic works are presented at The Vancouver Art Gallery, including his breakthrough series, Garden Projects (early nineties), which depicts scenes of kids playing in housing projects in Chicago; Souvenir (late nineties), showing black families in domestic spaces; and Vignettes (2003-2007), which places black couples in romantic rococo settings.

Better Homes, Better Gardens is reminiscent of looking at a mural that’s been painted over with automatic graffiti or tags. The splotchy drips and drops of paint are decorative to an extent, but also abusive in the sense that they force the content of the painted scenes into the background. Metaphorically, the violence done to the canvas can also be looked at as a violence upon the subject matter.

There is a hopefulness and an ironic, historical humor in Marshall’s paintings (featuring iconic characters like Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert and John F. Kennedy in Souvenir I and Souvenir II). Yet while nostalgia and sentimentality are restrained with deliberate flat, black subjects, the paintings are also pushed into a realm that hints at the complexity of black identity and representation. It reminds us of Homi Bhabha’s idea of hybridization in which he argues that colonization is not behind us, that it is reenacted and changing shape to exist today.

So how does this exhibition get framed within Vancouver? As a transplanted Vancouverite, Marshall’s paintings got me thinking about representations of blackness but also about my own identity as an Indo-Canadian person in Canada. More than fifty percent of Vancouver’s population speaks English as a second language. British Columbia is now considered Canada’s most ethnically diverse province, and the city is home to a relatively large population of Indo-Canadians and one of the largest diasporas of Punjabis in particular. So where is our experience represented in art? The most prominent representations are found instead in and by dominant media culture. Moreover, historical incidents involving new immigrant groups have transpired without the kind of acknowledgment or monumentalizing of atrocities (i.e. erecting monuments or holding services) that we have seen occur in the U.S. or in Western Europe. In British Columbia, this includes Japanese internment camps, Chinese railway worker exploitation, and the Komagata Maru incident, which prompted the Canadian government to enact exclusion laws preventing Indians from immigrating.

So while seeing Marshall’s large-scale figurative paintings at VAG provide an access point for thinking about black representation in America, framed in Vancouver, the exhibition also provokes questions about representation on home soil too. The adversity faced by the city’s ethnic groups is unique, of course, and not to be homogenized under one large minority umbrella. However, seeing this show in multicultural Vancouver is curious in light of Marshall’s comments in past interviews about how when he was a kid, he didn’t see blacks in pictoral space. Recently, Marshall told Vancouver newspaper The Georgia Straight that part of his own project has been to “figure out how to make paintings that could get to be part of the story.”

As I snuck a last glance of the survey of Kerry James Marshall’s works, I was reminded of a meeting that I had last year with the North Vancouver Office of Cultural Affairs, where I was asked for my input on how to include South Asians in the organization’s cultural and artistic representation. The task at hand felt well-intentioned but shortsighted: when does representation move beyond institutional tokenism? Marshall’s work also came up again in a conversation about representation I had with the curator of BC’s Surrey Art Gallery, Jordan Strom. Strom may be one of the most proactive Canadian curators researching Indo-Canadian art, making it part of his mandate at the gallery. He agreed that Indo-Canadians lacked representation in the Canadian art world. And just like Marshall recalls walking past great masterpieces when he was a child and wondering where he was represented, I couldn’t help but wonder if I ever thought the same thing when I was a kid too.