“I’m really trying to pay homage to the notion of the sublime and the abject together and using the aesthetic of rejection, or poverty, or wretchedness as a tool to talk about things that are transcendent and hopeful.” (Aimée Reed, “Interview with Wangechi Mutu,” Daily Serving, Apr. 12, 2010)

Wangechi Mutu was born in Kenya and lives and works in New York City. As the inaugural recipient of the Deutsche Bank Prize, Mutu had a large showing of her work up at the Deutsche Guggenheim this past June that included several of her signature strategically scatological collages and assemblages.

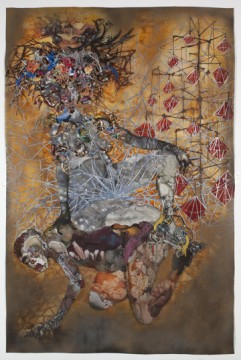

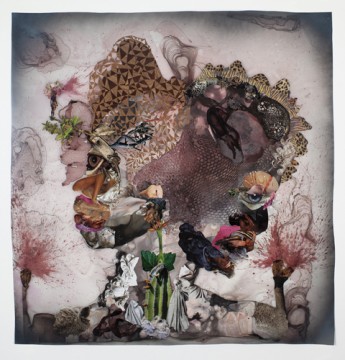

Having followed Mutu’s successes from early on in her career, it’s been dazzling to see her develop her present mode of working wherein she pieces together imagery culled from vintage medical illustrations, fashion and lifestyle magazines, pornography, and anthropological photographs and then embellishes them with glitter, paint, ribbon, and beads. Recently, for her exhibition at the Gladstone Gallery in New York, she also incorporated 3-D sculptural works as well. A close examination of Mutu’s 2D pieces reveal mylar resisting penetration from paint washes, with swirling pools of pleasing colors and curious microcosms of recognizable image fragments in unrecognizable contexts. Mutu’s work is beguiling and uncanny in the ways that it simultaneously entices and repels.

Dominated by depictions of the female figure, Mutu’s women are shape-shifting, hybridized forms whose meticulously reworked surfaces often belie their contorted postures, amputated limbs, flayed flesh, and stringy hair follicles.

By re-ordering disparate imagery of the natural world, such as bits and pieces from National Geographic, and splicing it together with mechanical imagery from Motorobike magazine, Mutu creates beings that blend all phylum of the animal kingdom together– or ones that look like they’re mostly machine-made cyborgs or out of this world aliens.

So, I think it’s sort of trying to slowly place this image up front yet again, and again, and again. A lot of work is about repetition; repeating the same thing, repeating the same image by going at it from different angles. I also think it takes a while for some things to be understood. I feel that what happens is that I have to keep continuing the work in order for it to be understood, ‘Oh, she kind of means it.’ When you are criticizing a culture from within, it is a little bit harder sometimes for people to accept it. (“Interview with Wangechi Mutu,” Daily Serving)

Wangechi Mutu, "I Sit, You Stand, They Crawl," 2010. Mixed media ink, collage on Mylar. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Gladstone Gallery. Photo by David Regen.

I agree with Mathew Evans, who has previously written that it’s reductive to read Mutu’s work as simply, “…Hannah Höch-referencing feminist readings, or Romare Bearden-referencing racial interpretations.” (Matthew Evans, “Wangechi Mutu: Between Beauty and Horror,” Deutsche Guggenheim Art Mag, 2010). And although gender and race are the subtext of much of her work, the subtler sides of what Mutu perceives as the exoticization of African women and the sexualization of African-American women, along with the history of colonization, also bristle and pulse through these pieces. In fact, the very media Mutu employs, much of it upcycled or creatively reused, is an equally important commentary on consumerism and the environment.

Wangechi Mutu, "Before Punk Came Funk," 2010. Mixed media ink, collage on Mylar. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Gladstone Gallery. Photo by David Regen.

I’m very excited to hear more about the form and content of Mutu’s work and look forward to the chance of hearing from Mutu first hand when VAP brings her to Chicago in April!

Pingback: Tweets that mention Wangechi Mutu | Art21 Blog -- Topsy.com

Pingback: The Art21 Blog’s Most-Viewed Posts of 2011 | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Contemporary Dance and African Heritage | Happening Africa

Pingback: Contemporary Dance and African Heritage

Pingback: Wangechi Mutu | Girls' Club