In the lead up to this year’s Academy Awards, I found myself on a few occasions defending Joel and Ethan Coen’s True Grit as something other than simply a good remake of a classic western. My argument in defense of their Oscar-nominated film more or less hinged on the basic point that True Grit can be enjoyed on a couple of levels simultaneously—enjoyed for the wonderfully told story and stunning visuals, and also enjoyed on a more conceptual level, which has more to do with the film as an homage to the genre of the Western. To this second point I would add that what makes their homage so compelling is that at the heart of the Coen brother’s fine iteration of the Western lies a wonderful paradox. What follows is my attempt to get to the heart of that paradox.

True Grit centers on a man named Rooster Cogburn, an aging and drunken U.S. Marshall whose violent past and reputation for fierce vengeance places him increasingly at odds with an increasingly more formal rule of law in the western territories, which threatens to render him and his methods of administering justice obsolete. Precisely for his problematic ways, Cogburn is prevailed upon by an outspoken and implacable young girl named Mattie Ross to bring her father’s killer to justice.

Befitting the tradition of the Western film, True Grit’s landscape is filled with sagebrush and its plot is centered on such fundamental concerns as the maintenance of law and order on the untamed frontier, justice overcoming injustice, and good confronting evil. With a range of frontier-hardened characters, a period musical score, and the requisite sweeping tracking shots to give a sense of the epic proportions of the western expanse, the Coen brothers patently employ many of the conventions and serialized forms of the genre. In fact, I would argue that the convincing realism and authenticity of their film is paradoxically fashioned through, and thus entirely and purposefully based on those very conventions.

Consider, for example, one of the most riveting scenes in True Grit, wherein Cogburn and Mattie, while traveling into Choctaw territory in pursuit of her father’s killer, come across a clearing where a body hangs from the branches of a tree. The tree is massive and the dangling body seems unnecessarily, almost impossibly high off the ground. The so-called ‘hanging tree’ is in fact a stock motif of the western genre, so much so that there was even a film titled Hanging Tree starring Gary Cooper in 1959. Not surprisingly then, the Coens linger on Cogburn and Mattie’s encounter with the hanging tree, the scene becoming particularly protracted as Mattie slowly climbs up the trunk and inches out onto the branch to cut the corpse down. It is a haunting scene, with the camera and the story loitering on the moment in a way that throws into relief the ‘hanging tree’ as a set piece of the genre, yet does so without disturbing the illusion of the film or its narrative coherence. This is the Coens at their best, as the scene is preoccupied with intertextual reference and fully complicit with the conventions of the Western, but not at the expense of the authenticity or continuity of their story or of the viewer’s immersive experience into the mythical spaces of the Old West.

This is not to say that the Coens don’t deconstruct many of the heroic myths that are staples of the studio Western—several killings in the movie, including that of Mattie Ross’s father, are in cold blood. Indeed, one of the film’s first scenes is of a court trial centering on whether or not in the course of his duties as Marshal Cogburn killed men that posed no imminent threat to him (the film makes clear that they didn’t). Of course, the Coen brothers are by no means the first to cast violence in Westerns an un-heroic light: in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven—perhaps the finest Western of all time—one villain is killed while sitting on the toilet in an outhouse, while in the film’s climactic scene, Eastwood’s character is accused of cowardice for shooting an unarmed man, to which he coolly replies that the man should have armed himself.

But what makes True Grit such an extraordinary film is that it registers as real and as authentic precisely because the Coens have so purposefully grounded it within a fully developed cinematic tradition. They construct an amazingly vivid Western not by meticulously reproducing what a frontier existence might have really been like, but by meticulously reproducing that existence as it has been represented in past Westerns. In fact, one of the great pleasures of their film is that the Coen brothers avoid turning these self-conscious stylistic and formal quotations and repetitions into postmodern triviality, but are instead able to present such a convincingly authentic time and place while never disguising its indebtedness to the conventions of the genre. I suspect that this in part explains why they chose to remake a Western rather than write their own, and why of all the ones to remake they selected a film that is practically synonymous with John Wayne—perhaps the most iconic Hollywood cowboy of all time (and who won the only Oscar of his career for his portrayal of Rooster Cogburn).

This paradoxical production of the real through the conventional in many ways becomes the very condition of the film. Take, for instance, Carter Burwell’s musical score, which lends authenticity to the film by being built around tunes and melodies that evoke period folk music and gospel hymns. In so doing, Burwell produces an extraordinary sense of time past. But he does so not by relying on authentic nineteenth-century frontier sounds, but by referencing a repertory of music founded on the soundtracks of John Ford’s and other studio era Westerns of the 1940s and 1950s. Thus, while True Grit’s score seems authentic, its authenticity ultimately derives from its indebtedness to Hollywood studio inventions. Burwell alludes to this referential aspect of the musical score when he remarked that he relied on a large orchestra for the “blatantly Western movie moments” of the script (Jon Burlingame, “Burwell in tune with Coen brothers,” Variety.com, Dec. 15, 2010).

It is precisely this building of the film upon the support of past cinematic practices that allows True Grit to open onto a familiar world that we know and recognize, to an authentic representation of the Old West and the untamed frontier. Thus, if the film loses grip on its credible claim to a certain truth (1880s frontier territory), it is reinscribed as another authentic truth, a cinematic truth. As Roland Barthes might say, in True Grit the past is offered up as style.

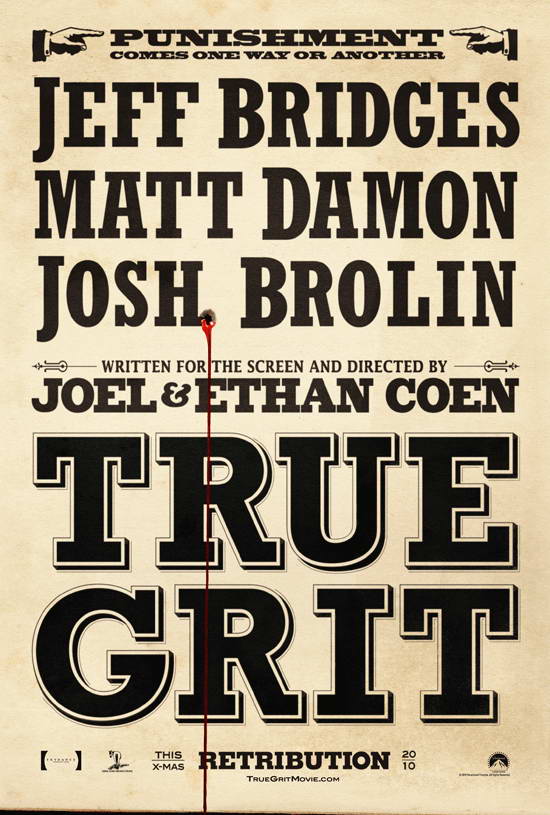

True Grit (2010) by Joel and Ethan Coen is on view now at a theater near you.