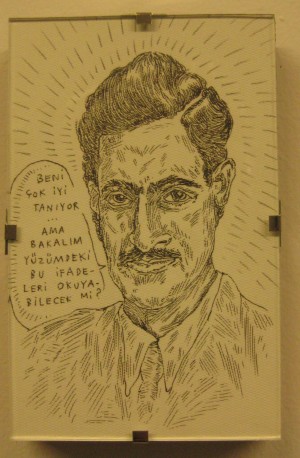

Nazım Hikmet Richard Dikbaş, "Beni Çok İyi Tanıyor... / She Knows Me Very Well...," ink on paper. 2011.

In talking to dozens of artists, curators, and critics over the past few months, over and over I have heard the same term used by those located within the community to criticize Turkish art: didactic. Merriam-Webster defines didactic as “intended to convey instruction and information as well as pleasure and entertainment;” synonyms include “sermonic,” “moralizing” and, “preachy.” Undoubtedly this sentiment is in part a reaction against much of the work produced in Turkey during the 1990s that dealt explicitly with issues related to the intersection of Turkish identity, culture, and politics. If in retrospect the manner in which some work addressed these topics seems heavy-handed, it could be argued that this practice mirrored the heavy-handed way in which the Turkish government was combating dissident elements of society during this period, particularly in regards to its armed conflict with Kurdish nationalist groups in the southeastern region of the country during the early and mid-1990s.

In 2011 there is no longer an open military conflict within Turkey’s borders, but Turkish culture and politics remain as complex and indecipherable as ever. This is a country fraught by shadow governments (both real and imagined), conspiracies, and hidden agendas. Turks never seem to take anything the government does at face value; there is always the assumption of incomplete information. Like an underwater oil leak, this opacity in Turkish political life filters out into the wider society, impacting not only the way individuals view and treat each other, but the way they think about themselves.

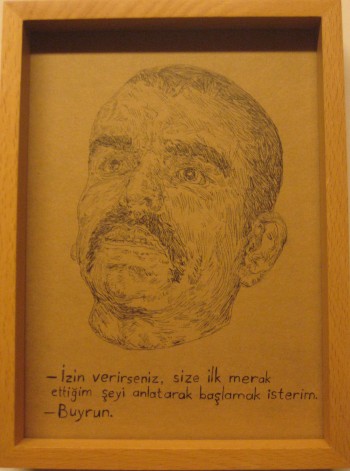

Nazım Hikmet Richard Dikbaş, "İzin Verirseniz Size İlk Merak Ettiğim Şeyi Anlatarak Başlamak İsterim / If You Allow Me I Would Like To Begin By Telling You About The First Thing I Was Curious About," ink on paper on plexiglass, 2011.

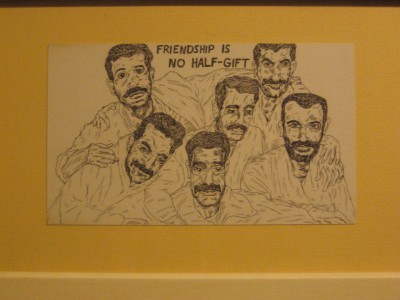

The task of making sense of the daily experience of living within such a convoluted political culture has been taken up by a new generation of artists who are exploring these topics on a more micro level and in a more personal way. This new approach is exemplified in Yeni Eğlenme ve Dinlenme Biçimleri/New Forms of Rest and Entertainment, the current exhibition of drawings by Nazım Hikmet Richard Dikbaş, on display at Istanbul’s Galeri NON through the end of this week. Dikbaş specializes in finely etched, comic-like portraits that capture the thoughts of anonymous characters in medias res as they meditate on moments of conflict, vulnerability, defeat, and alienation. Alternatively sympathetic and satirical, he shows a deep sensitivity to his characters’ basic humanity even as he pokes fun at their shallow insecurities and petty, self-centered obsessions.

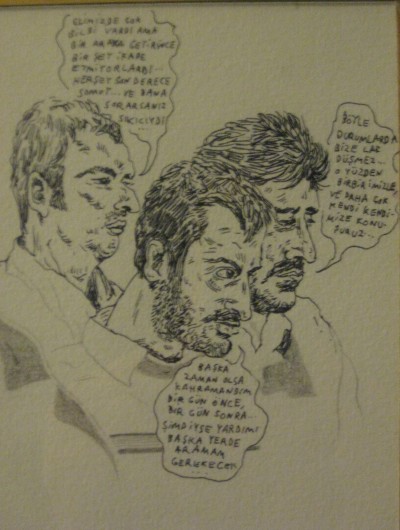

Nazım Hikmet Richard Dikbaş, "Başka Zaman Olsa Kahramandım / Another Day And I Would Have Been A Hero," ink on paper, 2011.

Comics, especially superhero comics, have traditionally relied on archetypes–Heroes, Antiheroes, Villains, Vigilantes–to communicate their meanings, and in the body of work currently on display at NON, Dikbaş is clearly concerned with exploring the limits of individuality. “There is no such thing as individuality,” Dikbaş tells me. “It depends on many things. You can refine aspects of character to make a unique personality.” This idea is further fleshed on in the exhibition’s wall-text, which asks “Should we too settle for the exaggerated statement that everyone has a distinct, unique personality? Or can we perhaps attempt to make out and identify the main personality-recipes shaped around self-interest, fear and stagnation? The latter may be more correct, but to keep the latter in mind whilst insisting on the former means giving everyone a chance.”

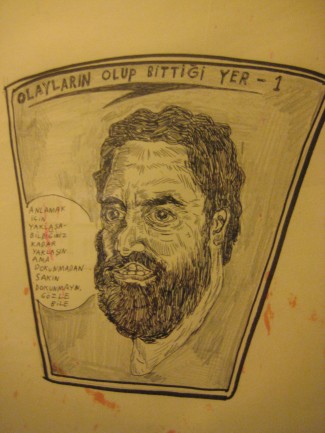

Nazım Hikmet Richard Dikbaş, "Olayların Olup Bittiği Yer – 1 / Where Things Take Place – 1," ink on paper, 2010.

The strength of Dikbaş’s work lies in his ability to visually hone in on this tension between the undeniable universality of certain experiences and character traits and the impulse to stake claims to uniqueness. Characters that possess grotesquely twisted mouths, frightening, unnatural teeth, humorous noses, and laughable mustaches simultaneously exhibit beautiful, emotive eyes and sensitive, long-fingered hands. Ridicule is balanced by empathy, humor by pathos. Even as the exhibition’s wall text announces its intent to defeat the “myth of the individual,” the blow is softened by the show’s title. “Rest and entertainment are very important,” Dikbaş laughs. “We have a lot of miserable people in this country.”

Nazım Hikmet Richard Dikbaş, "Friendship Is No Half-Gift / Arkadaşlık Denen Hediye," ink on paper. 2010.

The child of a British mother and Turkish father, Dikbaş was born in the United Kingdom, but at a young age returned with his family to Turkey. Through his older brother he developed an early interest in comics and graphic novels, and when his brother began to create his own characters, Dikbaş, in typical younger sibling fashion, followed suit (though he claims that he was “not naturally talented in the same sense” as his brother). Both boys were encouraged in their creative endeavors by their mother, an artist herself, and also by their maternal grandmother, who from England sent them classic British comics such as The Beano. The Dikbaş brothers were also avid readers of Italian comics such as Mr. No and Zagor, Turkish graphic magazines such as Gırgır, and American comics such as Mandrake the Magician and MAD Magazine. “MAD was very difficult to get [in Turkey],” recalls Dikbaş, “I probably got it from my brother. But we were very critical of the art in MAD, because we had such high standards from the Italian comics that we were reading.”

Like many artists, Dikbaş’s experience with art classes in elementary and high school were traumatic and “put me off terribly. We had these terrible topics, ‘The Festival of the Republic,’ etc. I almost failed my art classes.” But he always did drawings in his notebooks, and eventually he invented a character named Azza-man (a play on Superman, meaning “little time” in English) who looked like him and who “stood there and said things–slightly philosophical and cynical, but humorous.” Though Azza-man was mostly drawn to amuse his friends, in 2005 his close friend Memed Erdener interviewed him for Hayvan (“Animal” in English), the later incarnation of deli, the well-known Turkish humor magazine. Following the article, the magazine’s editor offered Dikbaş a regular strip, which he drew for over two years. This regular assignment forced him to think about his drawings in a new way, and it was through this experience that he honed his visual style. In 2007, Dikbaş and Erdener collaborated on The Empire Is Still Crumbling, a joint exhibition of their work held at Karşı Sanat, and in 2009 Dikbaş realized his first solo exhibition, Expecting Pleasure To Solve Problems, at the now-defunct Galeri Splendid.

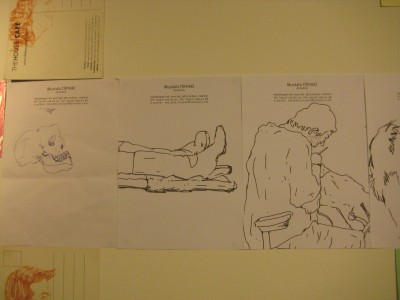

Installation shot, Yeni Eğlenme ve Dinlenme Biçimleri / New Forms of Rest and Entertainment. Galeri NON, 2011.

Dikbaş pays tribute to his lifelong engagement with informal drawing habits (okay, doodling) in an installation on the top floor of NON’s three-story exhibition space of small, unframed works, mostly done on odd bits of paper–postcards from Istanbul’s popular The House Café chain of restaurants, stationary from his dentist’s office, yellow notebook paper, colored Post-Its. Several of the drawings on his dentist’s stationary include sketches of Dikbaş’s girlfriend having her teeth worked on: one of her boot-clad lower legs, propped horizontally in the dentist’s chair (“she’s very proud of those red boots,” says Dikbaş fondly); one of the dentist (who happens to also be a friend), hard at work; and one of his girlfriend with some frightening looking dental implement protruding from her mouth. It is easy to imagine Dikbaş sitting there, idling sketching while he chats with his friend as routine dental work is performed.

Installation shot, Yeni Eğlenme ve Dinlenme Biçimleri / New Forms of Rest and Entertainment. Galeri NON, 2011.

These casual works not only attest to the artist’s constant engagement with his practice and observation of those around him, but also serve as records of fleeting moments. The fact that most of the subjects featured in these works are characters from Dikbaş’s everyday life–his friends, students, and colleagues–rather than invented ones, as in the more formal, framed pieces exhibited on thr floors below, serves as a reminder of the fact that we are all the monsters and heroes of our own personal graphic novels. We all part of the mass, yet still we strive to carve our niche in our corners of our worlds.