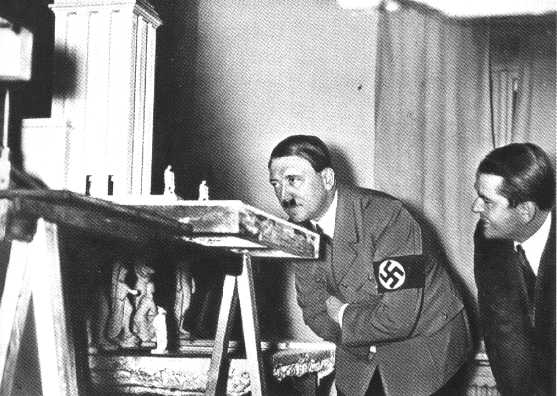

Will Corwin, "The Last Judgement" (2011). Courtesy the artist and George and Jorgen gallery.

There’s a long history of painters becoming architects and carrying their pictorial imaginations with them. Bramante’s Tempietto in Rome and Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library in Florence are examples of the painter’s transposition of pictorial approaches – composition, manipulation of light and tone – into an architectural language. Architecture gave back, too, providing painting with a perspectival framework by which to stage its spatial trickery. Painters often become architects, but it’s unusual for the reverse process to occur: however important painting is to the architectural processes of Zaha Hadid and Santiago Calatrava, one can’t imagine them ditching the grand ambition for the small. Will Corwin, a New York-based artist currently on show at George and Jorgen in central London, is a rare example of a trained architect turning to painting. It’s also an object lesson in architecture’s refusal to quit the aesthetic bloodstream, the impossibility of its being flushed out.

Corwin trained as an architect at Princeton and Cornell before turning his attention to painting. Working as an assistant to Sensation-era artist Richard Patterson, he was exposed to the slick painterliness of artists such as Fiona Rae and Gary Hume, and his early paintings engaged with their blend of the gestural and the deadpan. As they progressed, an increasing physicality crept into Corwin’s work: loading concrete and thick plaster onto the surfaces of his paintings, he seemed intent on literally weighing them down. For Corwin, a painting is a thing of the world, not simply in the world, and this preoccupation lent his works the sculptural qualities of immediacy and presentness. Now, in his new show in London, Corwin has followed that trail both forwards and backwards: his paintings have become not sculptural but architectural. It’s a kind of a homecoming.

Will Corwin, "Hamburg Peephole 1" (2010). Courtesy the artist and George and Jorgen gallery, London.

The Last Judgement, the centerpiece of Corwin’s installation, is a tall set of four-tiered wooden shelves that span the width and the height of the gallery. Knocked together with careful casualness (screws jut out at wild angles, the wood splinters at its edges), the shelves recall strictly functional units in an artist’s studio, and the objects they support suggest that too. At the bottom level, shards of broken ceramic, painted in the muted primaries of sun-bleached tiles, spill out over the limits of the shelves and crumble on the floor. One level up (about shoulder height), tiles of white plaster are stacked to resemble small buildings (they’re like miniature versions of Anselm Kiefer’s unsteady concrete watchtowers); a couple have been knocked down. There’s an evolutionary process to this, it seems: the penultimate level (there’s a doorway set into the shelves, so it’s over your head) is a row of untouched, vein-streaked large stones. At the highest level, plaster panels are stacked haphazardly, like books. They’re remnants of his own earlier painted works.

Corwin’s piece is a kind of hierarchy of sculptural material – from made to found – and its reference to the artist’s earlier practice suggests the taxonomy of memory. Its stratifications, explicitly inspired by the Last Judgement mosaic in the cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Torcello, near Venice, imply both ascension and damnation: the cracked plaster shards on the lower rung have a visual heaviness akin to the lumbering bodies of the hell-bound, and the caked plaster panels, despite their physicality, have something of the delicacy of fluttering angels’ wings. Weight is naturally implied in Last Judgment scenes, the soul’s weighing on St. Michael’s scales, and the gravitational scattering in the bottom two shelves might be seen to allude to the dead weight of the mortal life. However, Corwin’s real fascination here seems to be a profoundly architectural one – the role of space in framing human experience – and it’s a theme explored in smaller works in the exhibition. Diet of Worms, a dramatically cantilevered wooden structure punctured with two eye-holes, is a peepshow activated by the light of the street whose interior reveals small plaster panels stacked up and leant over to suggest an architectural model, half-dismantled, as though caked in dust. Smaller peepshow-style boxes, roughly knocked together, are suspended from the wall, revealing similarly quasi-architectural dioramas lit with spots of light from drill-holes. The effect is that of looking into a store cupboard of unrealized architectural models, whose insistent modernism (they recall a combination of Vantongerloo’s cubic constructions and Le Corbusier’s light-as-air space-making) gives them an air of melancholy and menace. Like Cornell’s (though leached of their dreamy romanticism) Corwin’s boxes make a virtue of their smallness, obliging the viewer to stoop down, Alice-like, and peer in, adjusting only partially to the half-darkness and restricted vision. Like architectural models, Corwin’s works are materializations of ideas that will never see their literal fruition. You just can’t quite see it happening.

Pingback: Letter from London: Grave Architecture Art21 Repost | Refining Your Art Practice