Robert Whitman, performance for "Passport" on the Hudson River

Note: The Saturday, April 16 performance of Robert Whitman, Passport, has been cancelled.

The Sunday, April 17, 2011, performance will take place as scheduled at 8pm.

Robert Whitman is 75 years old. Talking to him is like if Tristan Tzara swallowed Carl Jung. The artist is a visionary who is gripped by the mysterious power of the image. In the late 1950s and 1960s, Whitman sought to innovate cross-disciplinary art forms. He founded the organization, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T) with Robert Rauschenberg and engineers Billy Kluver and Fred Waldhauer. One of their collaborations, Nine Evenings: Theater and Engineering held at the 69th Regiment Armory in 1966, is known to have involved eight or nine cars with men holding projectors in the back seats.

Robert Whitman, "Two Holes of Water -3," 1966

Whitman likes the spectacle that turns into an immersive experience that can be viewed from multiple perspectives. His upcoming piece, Passport, premiers April 16-17 at Riverfront Park on the Hudson River near Dia:Beacon, New York, and Alexander Kasser Theater at Montclair State University, New Jersey. At this time, the performance at Riverfront Park is sold out, while seats at the Kasser are still available. Imagine that, to be wise, still making work that’s hot, and to have survived Allan Kaprow as Happenings maven?! Fortunately, I got to interview Whitman before going on location on the Hudson River.

Marissa Perel: In Passport, you’re going to be using pre-recorded video projection, live performance, and real-time streaming of the actions and environments of Riverfront Park and the Kasser Theater. How do the two locations connect? How do you set up each location so that it can be in dialogue with the other?

Robert Whitman: In terms of the set-up, I have the privilege of working with a wonderful production crew. I have many hands and people working with me to make the two locations part of one piece. I wanted to create a simultaneity of experience made up of two distinct environments. What performers can do in the Kasser Theater as an indoor venue, they can’t do on the Hudson and vice versa. But all of the actions will have a vocabulary and rhythm that unifies them.

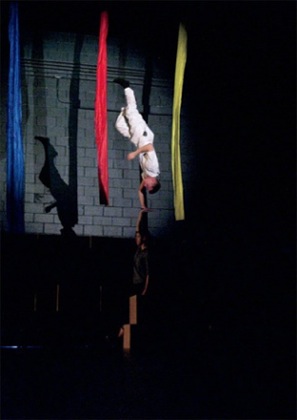

Rehearsal for "Passport" at the Kasser Theater

MP: Like magic! How do you create material for these actions? It seems like you are invested in something verging on the archetypal, how do you create performance that conveys the images you are after?

RW: At a certain point, you have a vocabulary and that’s what you have. As much as you try to escape your images and forms, you can’t. You end up rephrasing and making more articulate forms that have surfaced over the years. I am invested in the physical nature of performance, I like using the performers as workers, not just performers. I have done a lot of communication pieces and it is always interesting having one place speak to another. It’s a metaphor for the possibility of cultures communicating.

MP: It seems as though there are many forms communicating with each other, performance, video, objects, sound, feeding back into one another through video outside (on the Hudson River) and inside (the theater). Tell me more about this methodology as a metaphor for cultural communication. Do you see Passport as having a political impact?

RW: I am interested in the psychic value of my work, and I care about the layers of meaning and subtlety. Work that is explicitly political stops the experience right there because it happens within a known framework. It’s not written in scripture that everyone has to see the same thing at the same time. It’s interesting when people get together and have the same experience, but it’s different. Transmission over space and time has a quality.

MP: It’s occupying this space between the real and the imagined.

Image for "Passport" from the Kasser Theater

RW: Yes, and it’s that Duchampian answer of the viewer finishing the work by seeing it. Working between media, I want the ability to go after what I think is interesting or unusual, a mistake I couldn’t imagine happening that becomes serendipitous.

MP: What images or events have compelled you to explore this dream-like space or “quality”?

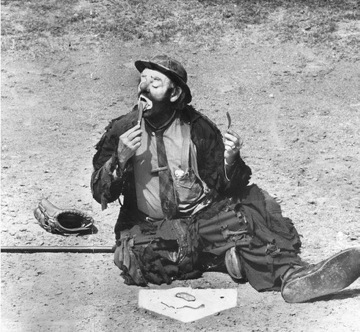

RW: When I was a little boy, I went to the circus. This was during WWII, and in those days there was a clown named Emmett Kelly. He was dressed as a Depression-era hobo. He came out into a spotlight on the floor, and he had a broom, he tried to sweep away a beam of light that moved from place to place on the ground, and he couldn’t. Then he found a rug, and finally “swept” it under the rug and then the whole place went dark.

Emmett Kelly as the Brooklyn Dodgers mascot, April 15, 1962 Photo: Art Rogers/ L.A. Times.

It was a piece they didn’t ever want him to do because it wasn’t funny. It was too depressing. I was looking around at the audience and wondering if they realized that they had just seen something else, something of death, it was like an angel came there. For a minute we were no longer at the circus, and the clown was not a clown. For me it’s about when something or someone transcends a known function and becomes something else.

I think that must have been when I realized that I was an artist. I wasn’t going to grow up to be a fireman or anything like that. An angel or witch visited me and said, “That’s it, kid!”

MP: Yeah, I know what you mean. You’ve been “touched” by the death-goddess, Art. That happened to me, too.

RW: (Laughs) Oh so fantastical!

"Touched" by the death goddess, Art — or in this case by Bonnie Tyler in "Total Eclipse of the Heart"

MP: How does it feel to have survived so many of your contemporaries as you continue to create major projects? Do you think about what it would be like to work with people who are no longer around?

RW: Lesson number one, never love people who are older than you. Ha ha. I still have Jimmy Dine and Claes Oldenburg around to keep me company. But yes, I do think of artists who played major roles in my life, and whom I always wish could remain a part of it. But once you’ve made the commitment to being an artist, you have to see it through and keep making it.

MP: What would you like audience members to come away with from Passport?

RW: I’d like people, at the end of the piece to be back in their own heads, to get back into themselves and relate this experience they just had back to who they are.

Last Man Standing: Robert Whitman with Carolee Schneemann, left and Trisha Brown, right