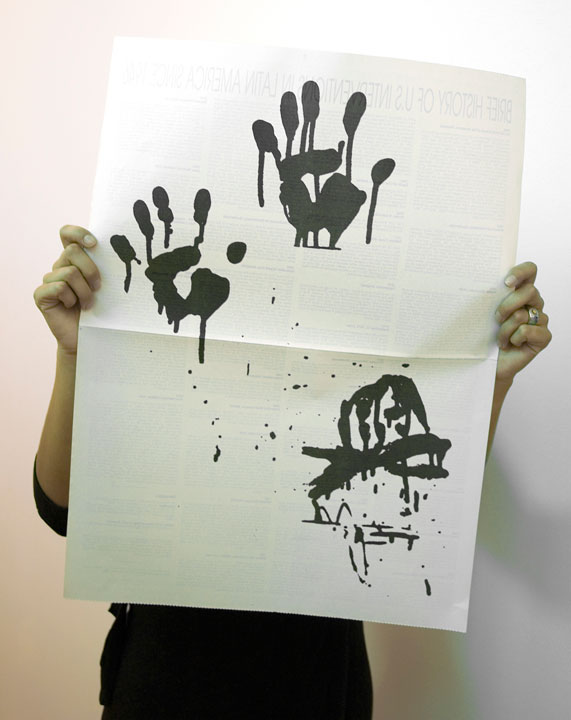

Carlos Motta, "Brief History of U.S Interventions in Latin America Since 1946," 2005. Freely distributed newsprint publication, 22 x 16”. View of a newsprint during exhibition at CCS Bard Hessel Museum of Art, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, 2008. Courtesy the artist.

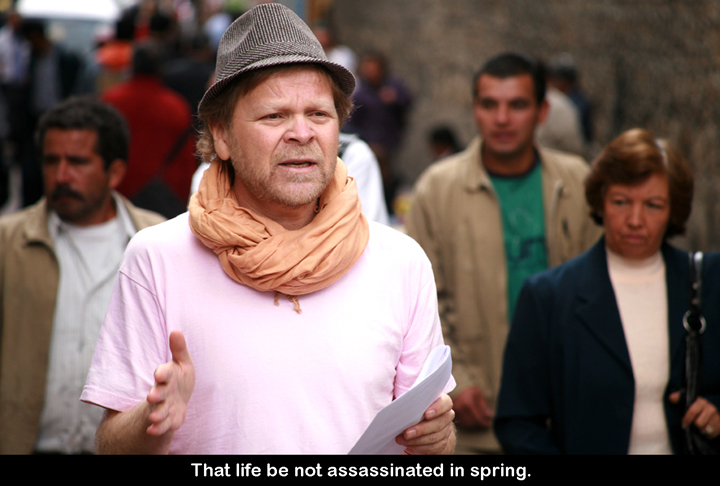

While Carlos Motta’s work exists through a number of different media, I think of it primarily as putting forth a series of socially and politically committed archives. These archives are focused through a series of different questions related to Latin American geopolitics and queer cultural politics. In one such archival work, a video/performance project called Six Acts: An Experiment in Narrative Justice (2010), Motta restages speeches calling for peace delivered by six Colombian left-leaning presidential candidates that were assassinated during critical moments in the nation’s history. By employing actors to perform the speeches in public places during Colombia’s 2010 presidential campaign, the work solicits response from passersby, many of whom are unaware of the speeches’ import, or when and by whom the speeches were first given. Like Mark Tribe, Sharon Hayes, and a number of other younger contemporary artists, Motta employs the reenactment of political speeches as a way of both engaging a viewer in dialogue about political histories and allowing submerged historical narratives to live again through the bodies of actors situated within sites of public discourse and exchange.

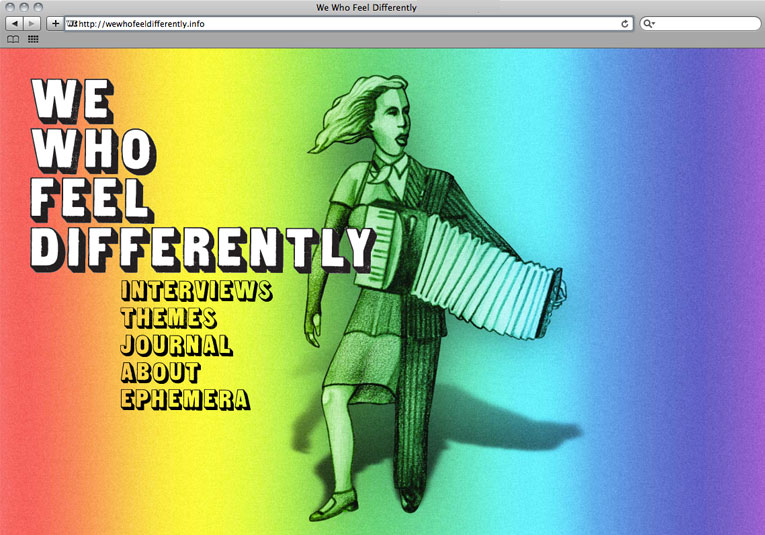

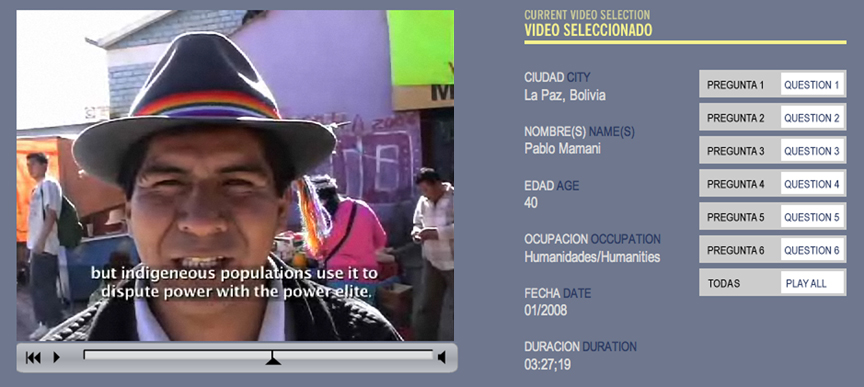

As in many of Motta’s works, Six Acts constructs a kind of archive, an archive of what has gone unnoticed and that is at risk of being forgotten by a culture’s memory of itself. One can witness a similar archival tendency in all the works of Democracy Cycle, of which Six Acts is just one part. In The Immigrant Files: Democracy Is Not Dead; It Just Smells Funny (2009), the artist collects interviews with Latin American immigrants/exiles to Sweden. Through the series of interviews, one becomes able to see the contradictions and antagonisms within Sweden’s idealized democratic system. Similarly, by collecting over four hundred video interviews with pedestrians on the streets of twelve Latin American cities in The Good Life (2005-2008), Motta provides his viewer with a variegated composite of how Latin Americans view the US’s role in Latin American geopolitics throughout the past century. While many citizens are enraged by what they perceive as a gross injustice committed against that region by the US, others are ambivalent, if not seemingly ignorant, of the US’s actions. In his most recent project, We Who Feel Differently, the artist and multiple collaborators explore a variety of problems surrounding contemporary queer and LGBT activist communities in the US and abroad. Conducting video interviews and collating and commissioning articles for a journal, We Who Feel Differently offers an extensive web archive on issues regarding sexual and gender politics and histories.

Carlos Motta, "We Who Feel Differently," 2011. Website (wewhofeeldifferently.info). Courtesy the artist.

Another project by Motta that attempts to intervene through the construction of archives as well as through the distribution and collation of information is the artist’s SOA Cycle (2005). Whereas the Democracy Cycle offers numerous perspectives on democracy within and without Latin America, SOA Cycle focuses specifically on the repercussions of US intervention in Latin America via the School of the Americas, a US government sponsored educational institution for training foreign military officials and personnel. Notorious for its role in training the leaders of death squads and military coups that terrorized Latin America throughout the 70s and 80s, School of the Americas changed its name to Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation in the early 2000s, yet its involvement in contemporary Latin American politics remains active and unchallenged. Through his project, which involves video, printed matter, sound installation, and photography, Motta disseminates vital information about the US’s troubling role in Latin American geopolitics.

As Motta’s photographs and installations of political graffiti from Latin America show [Ideological Graffiti (2005-2011) and Graffiti Cuts (2010)], it is often through fleeting cultural matter such as graffiti that one may bear witness to larger cultural sentiments and underlying popular dissent. In his installation Graffiti Cuts, Motta monumentalizes these sentiments by carving them into a backlit metal surface. Similarly, by contrasting photographs of physically present buildings with photographs of their absence, a project like Leningrad Trilogy (2006) bears witness to the threat of disappearance and the inevitability of cultural change. I am interested in these two projects, as they seem to extend Motta’s work as an artist-archivist invested in the liminal registers of social reality and political antagonism.

Through the construction of alternative sources of information and (counter) public discourse, Motta’s work focuses his viewer’s attention on a range of subjects crucial to struggles for democracy and autonomy among groups and individuals. Using the web and inexpensive printing technologies as tools of distribution, the artist’s considerable body of work bears witness to cultural memories in danger of remaining critically unchallenged, if not entirely lost to a public’s attention.

Carlos Motta, "United Latin America" from "When, if ever, does one draw a line under the horrors of history in the interest of truth and reconciliation?" (2009). Screenprint, 30 x 22”. Courtesy the artist and Y Gallery, New York.

1. What is your background as an artist and how does this background inform and motivate your practice?

I was born and raised in Bogotá, Colombia in the 1980s; a very difficult decade when violence was present throughout the country in very real ways and it transversally affected all sectors of society. The noise and climate of violence didn’t discriminate, even if social and economic privilege served as a shield to protect me from the more atrocious manifestations of violence that affected underprivileged folks in urban and rural areas. That history of political violence and the harsh realization of the contradictions inherent to social and economic inequalities have shaped the way I have learned to see and relate to society and politics at large.

Coming out as a gay man in Colombia in the 1990s, which is a very religious and socially conservative country, was also a formative experience. I learned to cope with the anti-gay bullying at school and the constant discrimination against sexually diverse people within cultural norms, conventions of language, and the mindless mainstream media. These two factors helped me to develop awareness about “difference” and its representation, which has been foundational to the way I think about the process of producing and communicating through art.

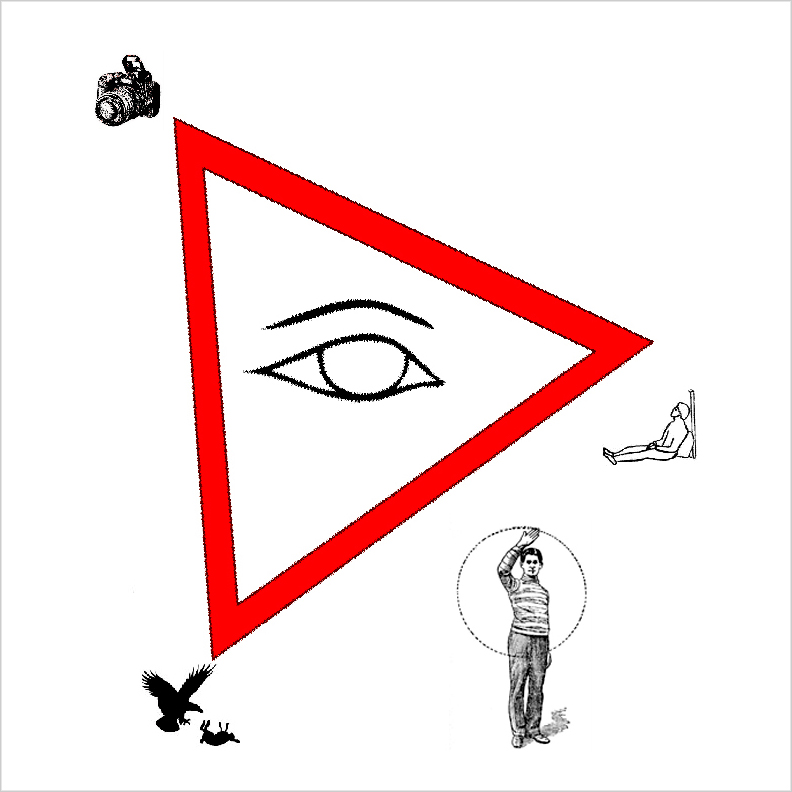

Carlos Motta, "The Triangle (The Ethics of Photographic Representation) (Inspired by the reading of Ariella Azoulay’s “The Civil Contract of Photography,” Martha Rosler’s “In, Around and Afterthoughts on Documentary Photography” and David Levi Strauss’ writings on Kevin Carter)," 2011. Letterpress print, 30 x 30”. Courtesy the artist.

My training as an artist was initially in photography, a medium that fascinates me because of its inherent relation to issues of “representation.” Who is shooting? Who is being shot? Who is looking? What are the multidirectional relations at stake within that triangular relationship? The ethical and aesthetic challenges posed by these questions demand the breaking down of subject positions and reveal the hierarchical way that we have traditionally learned to think of representation: that an image “of” something is made “for” someone’s (uncritical) consumption. Shifting and turning around this one-way relation to highlight the responsibility of the viewer to the subject and the maker, the maker to the subject, and the subject to the viewer can lead one to productively consider the political challenges of representation. When we stop favoring the viewer and implicate him/her we confront social clashes, which are often irreconcilable yet offer opportunities to think through “antagonism” and “difference” ethically, aesthetically, and politically.

These issues are not exclusive to photography. Through my art projects I have researched, discussed, and problematized (self) representation by attempting to develop a documentary-based practice that uses particular political events as its subject and simultaneously reflects upon its means of production/consumption. The resultant projects exist as videos, photos, prints, and websites.

Carlos Motta filming one of the performances of “Dios Pobre” at the Museu Serralves, Porto, Portugal in November 2010.

2. Do you feel there is a need for the work that you are doing given the larger field of visual art and the ways that aesthetic practices may be able to shape public space, civic responsibility, and political action? Why or why not?

Absolutely, I think there is a need for (but not a lack of) art projects that engage directly with social and political realities in thorough and direct ways that aren’t merely referential, circumstantial, or aestheticizing. I am interested in art projects that show long-term investment in research and aesthetic questions, and that are a vehicle for communication and social transformation. Which is to say, art that is not only an end in itself. In other words, I believe in art as a methodology and as a practice, but not that much in the static life of the art object, and the seemingly undisputed autonomy it is claimed by many to have. I am bothered by the common affirmation often expressed by artists: “All art is political.” I find this statement unrealistic. In saying it one conveniently ignores the complex web of economic and political implications that exist beyond the art object itself. Art can be political only if you intend it to be; only if you insert it in a specific context where it can do the work you intend it to do.

One of the biggest mistakes we often make is to believe in the monolithic category “ART IS,” which I believe is at the root of the debate (and skepticism) about the political efficacy of art. I don’t think art “IS” one thing in particular. It shouldn’t be thought in the singular, but rather embraced in the plural: Art(s), rather, are, whether objective and social, symbolic and didactic, pedagogical and entertaining, etc. I don’t mean to relativize or to dichotomize these categories, but to insist that a plural frame of mind produces a positive, inclusive, and liberatory rhetoric that resists the dominant and reductive forces of the art market and art history which have through the forces of authoritarianism, paternalism, and capitalism staked their claims over art.

Carlos Motta, "Six Acts: An Experiment in Narrative Justice," 2010. "ACT IV: Carlos Pizarro" (performed by Lisandro López). Photo: Carlos Augusto Botero. Courtesy the artist.

To me, the most interesting artists are those who seek to influence and affect reality, those who are politically audacious, self-reflective about their use of art mediums, and more importantly, those who take stands through their works. “Subtlety” and “ambiguity,” terms often used to praise the quality of a work of art, are not that interesting to me at this point in time.

I firmly believe that artistic practices can “shape public space, civic responsibility and political action,” as you say. A good example of this is the amazing work done by ACT UP activists in the 1980s and 1990s, which often used artistic strategies during their direct actions (performance, graphics, etc.) to call media attention, and developed video activism, producing works that responded politically and poetically to the crisis.

Carlos Motta, "Six Acts: An Experiment in Narrative Justice," 2010. Partial view of the video installation at the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Oslo, 2010. Courtesy the artist and Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo.

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired your work? Please describe.

There are so many that it is hard to name just a few, so I will mention some practices that have inspired me in the last couple of months:

- Queerocracy is a recently formed queer grassroots activist organization interested in using direct action and creative tactics to fight for social justice. Its members are primarily students under 30 years of age; full of energy they are taking on very important battles. Together with Queerocracy and a few other grass roots organizations we are collaborating on an event that will address the way immigrant rights and queer rights intersect in the public sphere in ways that both confront, challenge and transform the state mechanisms that police borders and bodies in the United States and other receiving states. The event will take place on October 10, 2011 and we are holding planning meetings every month.

- The queer art/publishing collective Against Equality, which focuses on critiquing mainstream Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans politics from queer perspectives. These folks are relentless in their dedication to fight for the social justice of queer and trans people who are often ignored by the rigidity of the “equality” rhetoric articulated by LGBT organizations and bureaucrats.

- Performer Mx. Justin Vivian Bond is making a public record of “V’s” “transness.” Bond has adopted the pronoun “V” and added the name Vivian to emphasize that V is neither male nor female, but trans. V’s music is beautiful, poetic and militant. The work is inspiring because it teaches us about self-determination in a pretty stuck up world.

- Tania Bruguera’s concept of “Useful Art,” which refers to art that is immersed “back into society with all our resources.” Bruguera is giving contemporary political art the central position that it deserves.

- Patricio Guzmán’s latest film, Nostalgia for the Light, is a masterpiece! The film takes place in the Atacama Desert in Chile and brings together in a remarkable way the stories of three groups of people that are looking for the truth about the past: Astronomers that study the stars, forensic archeologists that look for traces of past civilizations, and the women of the disappeared who continue to look for the remains of their loved ones since the Pinochet regime vanished them. This film is a poetic and political manifesto. Rarely do aesthetics and politics work so effectively together.

Carlos Motta, "Queer Planet," 2009. Large-scale posters installed of the façade of the museum at the 2009 International Incheon Women Artists' Biennale, Incheon, South Korea. Dimensions variable Courtesy the artist.

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

I recently completed a six-year cycle of five projects, the Democracy Cycle (2005-2011), through which I approached the concept of “democracy” from a variety of “marginal” social perspectives: U.S foreign policy (The Good Life, 2008), political asylum (The Immigrant Files), “Liberation Theology” (Dios Pobre 2010), memory of political conflict (Six Acts, 2010), and queer activism (We Who Feel Differently, 2011). Through each one of these projects, I wanted to question democracy, a system of government that has been idealized as the only functioning political system, yet which also permits the exclusion and discrimination of certain individuals and communities, and is complicit and co-constituent with the historical development of deregulated global capitalism. All of these works were stimulating to work on because they challenged me to work with people’s life experiences and to understand the fantastic ways in which these individuals have been fighting to achieve political representation on their own terms against dominant systems of political representation.

My favorite project at the moment is We Who Feel Differently, a web archive, journal and book that bring together a series of queer critiques of normative ways of thinking about sexual difference in various geographic contexts. I wanted to articulate a very distinct position about the role of “difference” regarding sexuality and gender. I think of being Queer as a critical opportunity to think about society and politics at large. I am interested in the ways that being queer can actually help us challenge a system that demands us to assimilate in order to belong and be accepted. In that regard, the work attempts to document the work of activists and thinkers who actively fight to achieve equal rights without replicating heteronormative logics.

Carlos Motta, "The Good Life" / "La buena vida," 2008. Website (la-buena-vida.info). Courtesy the artist.

5. What projects would you like to work on in the future? What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

I have begun a new long-term cycle of works about the politics of “sexual difference.” The first project (tentatively titled The Neutral) deals with gender self-determination, an idea that is very challenging to a society that has organized itself around a very rigid gender dichotomy. I am interested in the work that trans and intersex activists are doing to build safe spaces to express their chosen gender.

Generally I am interested in continuing to document histories and community efforts that tend to be neglected by official historical narratives. I also want to challenge myself to reinvent my methodology often and to keep an open mind to the teachings of others that an art practice has constantly introduced me to.