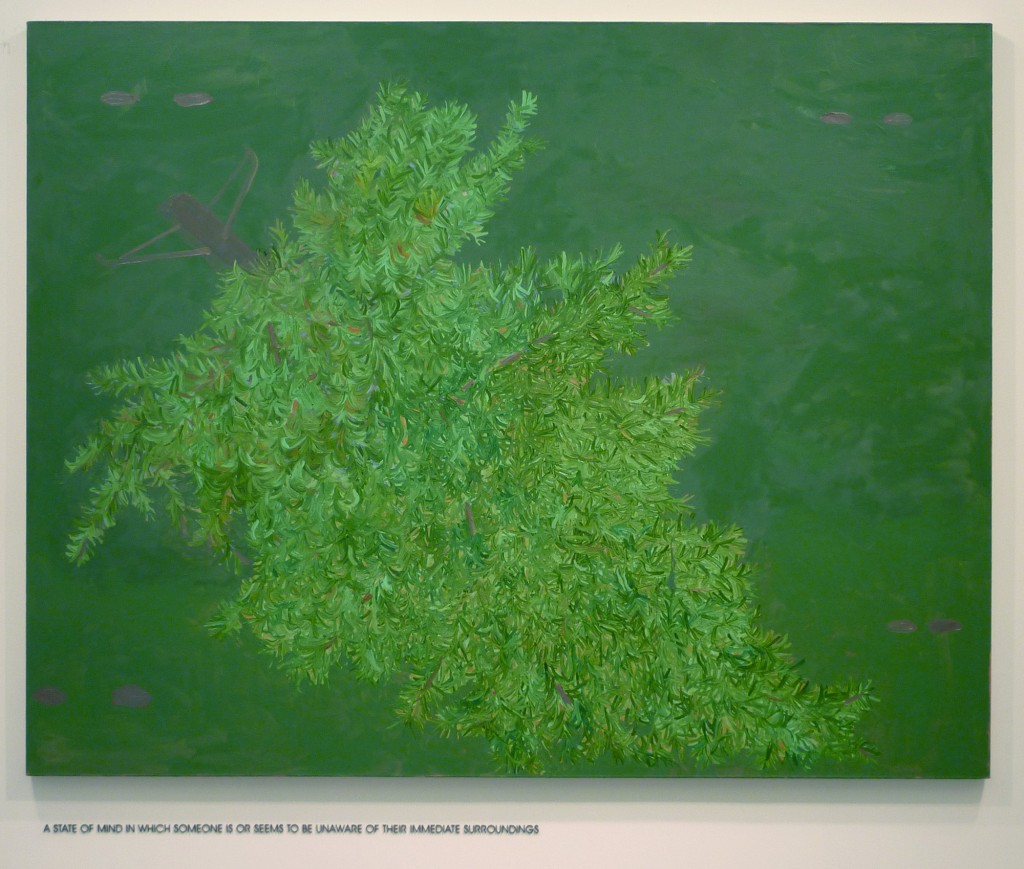

Alisha Kerlin, "A State of Mind in Which Someone Is Or Seems To Be Unaware Of Their Immediate Surroundings," 2011

I’ve held my own definition of literacy for some time now: that becoming increasingly literate is essentially seeing the world with increasing nuance. Greater literacy means grasping the many shades of difference that might be attached to any one object or idea. Knowledge, on the other hand, is the way we make useful all of that nuance, organizing it and making connections between it. In this way, literacy and knowledge are codependent yet somewhat counterproductive forces of language. Literacy expands while knowledge consolidates. To me, one of art’s great uses is its ability to restructure the paths that knowledge builds between information without abolishing the delicate nodes of nuance whose recognition come at the price of careful observation and imagination.

I didn’t immediately connect Alisha Kerlin’s paintings with this idea of nuance and knowledge. My first impressions were of solitude and the isolated objecthood they depicted. And these things certainly exist in the work. In fact, Kerlin’s words for the press release of her current show echoed my own thoughts by giving direct prominence to the ‘solitude’ of the playing cards, the carrot, or the tree in her paintings. But the isolation she imposes on her subjects gets far greater mileage than a simple feeling of aloneness, and goes beyond a metaphor for the long-laboring studio artist (or the lonely painting on the wall).

It is precisely the solitude in her work that allows layers of nuance to move around and reconnect in unexpected ways. In their isolation, Kerlin’s paintings function much more closely to the slippery, meaning-stuffed, ever-evolving nature of language itself. They read like entries in a lexicon, but not so much a dictionary, more like a thesaurus, in which the identity of the central component is in a swirl with its tangential comparative other selves. The title of her current show at Zach Feuer in Manhattan, Perceptible by Comparison, certainly points to this idea. Through an applied solitude, the paintings, the things depicted in the paintings, and the viewer alike are loosened of their normal connections to one another and to their own selfhood and enter a kind of drift or hovering. What follows seems to be a desire to mark out the undefined and unnatural place of the rectangular painted surface and to reconnect meaning between the various parts. Such was my reaction to Kerlin’s paintings of measuring tapes stretching across amorphous fields of paint, or subtly plotted gestures that often appear in the corners of her paintings. Absent normal associations, we feel the need to reorient ourselves by plotting a new set of guides.

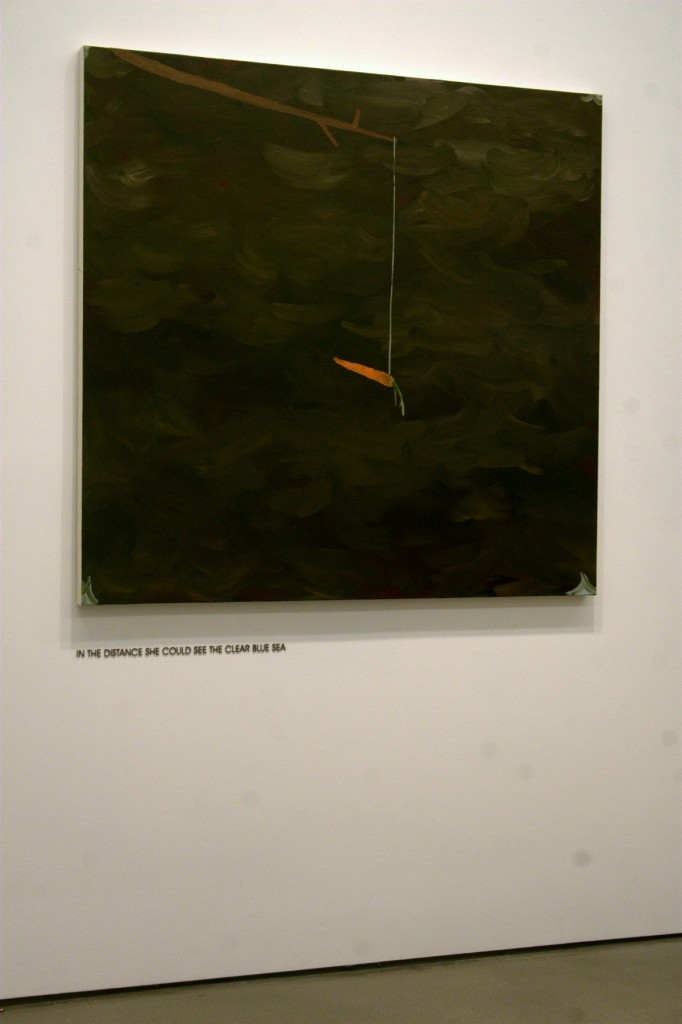

Hovering appears throughout Kerlin’s work: vultures in the sky, a carrot on a stick, playing cards floating on some watery or cloudy mass, a felled tree not quite settled to the ground. To hover is a peculiar action in an artwork because it does not let the viewer rest on a definite idea but neither does it allow us to roam free to whatever meaning we wish. We see the thing that is depicted plainly, and yet its strange slow movement causes us to doubt its identity. The paintings hang like illustrations from a story that no longer exists. Equal parts unequivocal and obscure, the levitating or dangling images ask the viewer for completion while taunting with the possibility that there is only one correct answer, or none at all. Not left to freely choose how to make sense of her dexterously painted figurations and their grounds, Kerlin specifically implicates the viewer and blends his position with that of the artist. We, too, must play the hard game and assemble the fragments of perception into a serviceable whole.

Additionally, Kerlin’s works are decidedly outwardly oriented. Often the completion of the painting depends on some implied exterior force, persona, or possibility. In They Looked Up When He Came Quietly Into the Room (2011), circling vultures are controlled by mysterious blue rods that run to the painting’s edge without revealing the hand that guides them. The same is true with a carrot dangling from a stick in In the Distance She Could See the Clear Blue Sea (2011). In her many paintings of failed hands of solitaire, we may wonder what decisions could have been made differently that would have solved the game or at least left us with a different failure and therefore a different composition. For all the trappings of traditional canvas painting, these seem to be less about the interior singularity of each surface and more about how the solution for each image will be inflected by its varying contexts. This focus on the contextual world of the painting leads it do be, like any word, perpetually redefined.

Kerlin’s focus outside of her paintings’ surfaces — and their relationship to language — goes a step further in this exhibition with an unusually prominent display of the paintings’ determined yet elusive titles. Rather than the ever-present “Untitled” found in much of contemporary art, or a subtle wall text, Kerlin had the sentence-length titles laser cut from plywood and adhered to the wall below the paintings. They are unavoidable second acts to viewing the immersive, swimming surfaces of paint. If the paintings themselves delight to be found in an array of possible shades of interpretation, the titles work like anchors to singularity, leading the viewer to a direct read. If we continue the analogy of a lexical entry, the titles could be the example phrase, showing how this particular image might be used in context. They reveal in their prominence and their specificity a bit of Kerlin’s own thoughts behind the painting’s existence, and therefore work as a guide to what meaning we may deduce. Instead of a fully detached solitude, the paintings are tethered to intent by a title that’s as physically present as the canvas, giving a certain range to the variation of nuance that’s permissible and an unmistakable association with language itself.

Ultimately, Kerlin’s lexicon may be one of verbs: to hover, to lead, to obscure, to limit, to fall (without making a sound), to isolate, to float; their action built on a reciprocating relationship between mystery and specificity couched in each surface and weighted by each title. In these painted spaces of stilted activity, our knowledge of the depicted forms breaks down. We find ourselves referencing the various paintings, like thumbing through a thesaurus, to reconstitute the words we already know with a new understanding.

Alisha Kerlin: Perceptible by Comparison opened Wednesday, June 29th and is on view through August 12 at Zach Feuer Gallery, 548 West 22nd Street, New York, NY.

Pingback: Alisha Kerlin : LOST CAT | Flying Object

Pingback: Flying Object | Alisha Kerlin : LOST CAT - Flying Object