Being a fan of “themes,” my posts as guest blogger for Art21 will revolve around (digital) archives and feminist/women’s art (histories), issues that my own work is heavily concerned with. As such, I want to begin with a little shameless self-promotion.

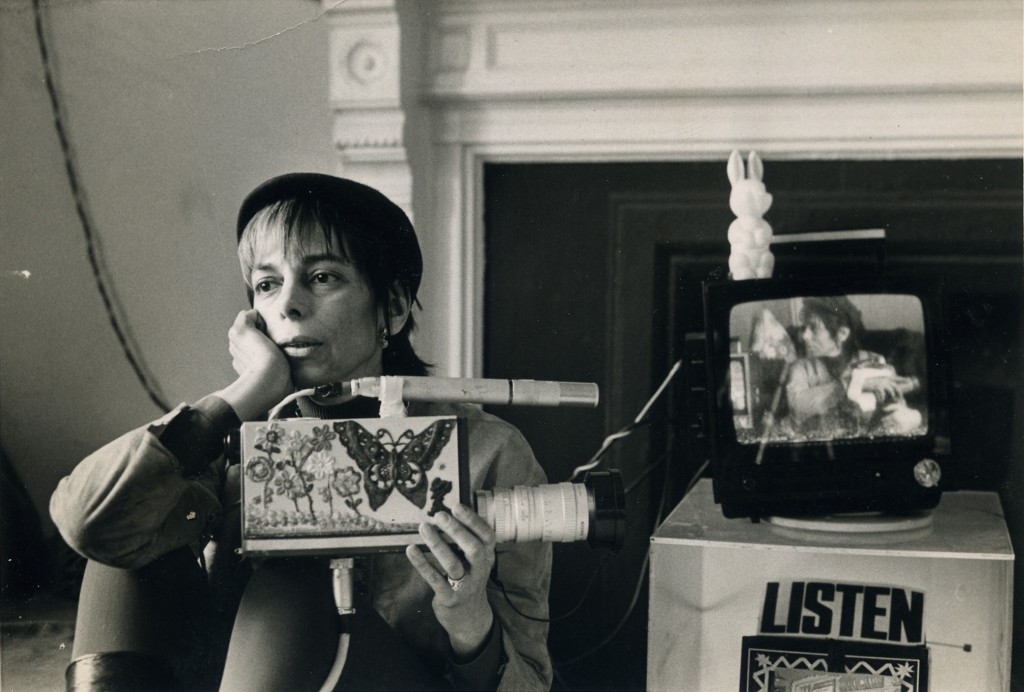

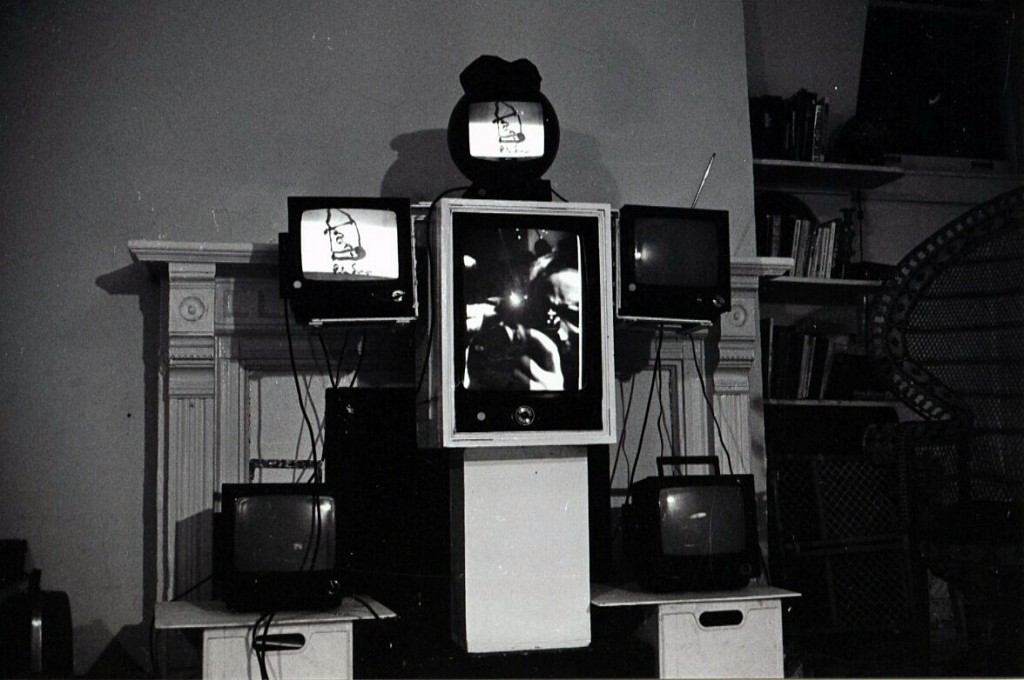

Last year, I initiated an archival project bringing together the work and documents of Shirley Clarke’s 1970s video workshops. Though Clarke is more well-known as a filmmaker, for films such as The Connection (1961), The Cool World (1964) and Portrait of Jason (1967), Clarke’s work in video was just as interesting and groundbreaking as these films. From 1969-75, Clarke ran these workshops out of her Chelsea Hotel studio, a triangular-shaped structure dubbed the “Tee Pee” by the New York early video community. She divided her home into several smaller spaces on several levels, all of which she equipped with cameras and monitors stacked on top of one another in totem-pole like structures to resemble the human form. The body of these “totems” was a large monitor, flipped on its side; the arms and legs were smaller monitors, and the head was a circular shaped “ball” monitor. Spaces were wired for video and audio and images could be transmitted simultaneously between them using a custom-made patch board. The participants of these workshops―a disparate and ever-changing band of video makers, filmmakers, poets, artists and dancers―called themselves the Tee Pee Video Space Troupe.

I discovered Clarke’s video workshops through a 2004 essay for Millennium Film Journal written by Andrew Gurian, a participant in these workshops, and became interested in finding out why they were near absent from the numerous canonical (read: gallery art) and alternative accounts of early video, despite the fact that they were attended at one time or another by video art pioneers such as Nam June Paik, Steina and Woody Vasulka, and the Videofreex.

In my view, there are a number of central reasons why Clarke has been overlooked in existing histories of early video. On a logistical note, the 1/2 inch tapes from these workshops have never been preserved and, as such, are not viewable, limiting the material available for historical study. More centrally, however, Clarke’s workshops reflected a philosophy of video as a process art form and the tapes from these workshops were meant to be ephemeral. Unlike many other video practitioners from the New York scene, Clarke saw video as an inadequate medium for documentary-style tapes. The Portapak cameras of the time produced murky looking tapes with no clarity of image, prone to glitches and drop outs. Clarke thought video was more suited to processual explorations in “videospace.” As a consequence, the tapes of her workshops were viewed as relics, mere inputs that formed part of a larger process or performance.

Clarke’s workshops also revolved around video “games,” devised by Clarke and her daughter Wendy, that Gurian suggests may have been perceived by some onlookers as “inconsequential childish activities, the sort of thing a sixth-grade art class might undertake.” These included “Head-Body” games, where participants divided into the different spaces of the Chelsea to produce live video feeds of their legs, arms and faces to create a collage of body parts, dancing together in real-time, and video painting, a game that asked participants to make self-portraits by only looking at monitors. Participants would stare at their image on one monitor, and their “in progress” paintings on another. The products of these games would then be remixed together, as part of video playback sessions, where workshop participants gathered to reflect on the weekend’s activities.

The importance of playing and having fun with technology was integral to the experience of Clarke’s workshops and an understanding of the role of playfulness and fun in relation to the history of technological experimentation in general is currently being explored in these exhibitions. Such experiences are often left out of the histories of media experimentation; they are discarded, or seen as superfluous, to the end product (i.e. the video art that is exhibited, distributed, and screened in galleries and cinemas.) Clarke put play and fun at the center of her workshops, and any attempt to historicize and archive this work cannot ignore this.

After Clarke’s death in 1997, her videos, along with the documents from these workshops, were placed in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Film and Theater Research, where they currently reside―closed off, unwatchable, and inaccessible. The question of what to do with these materials is a pertinent one, made all the more vital because these tapes will soon be unsalvageable. And though Clarke saw the tapes from these workshops as less important than the experience of taking part, she did indicate her desire to have these tapes saved. She told DeeDee Halleck in 1985, “I have 400 tapes, half inch, black and white, that were done during years 1969 to 1975. They’re video experiments by so many people who worked with us. Raindance, the Videofreex, people like Frank Gillette, Vicki Polan, Andy Gurian, Shridar Bapat, David Cort, Nancy Cain. That whole batch of tape should be saved somewhere.”

These tapes are records of the community of video artists who united to play together in Clarke’s workshops. They are fragments that throw into contention an oft-repeated narrativization of this moment as comprised solely of activist-artists using video in search of clearly-defined utopian aims, and point towards a messier, more haphazard mode of engagement typified by playful experimentation.

Throughout the process of creating an archive to represent the history of Clarke’s workshops, I have asked myself one central question: How should one create an archive that accounts for the ephemeral and playful nature of Clarke’s video workshops? My answer is a model that proposes to offer researchers and audiences playful encounters with the historical materials of Clarke’s workshops, while situating these encounters together with participant’s oral histories, as well as other ephemera, including photographs, news articles, handouts, letters, and posters. Whereas archives are often understood to be places where the past is hermetically preserved, this project revolves around an understanding of archiving that is at once playful and participatory. I do this by inviting users to navigate the archive and treat the videos from Clarke’s workshops as they were initially viewed by Clarke herself―as material to be used as part of a process.

The videos from Clarke’s workshops, once preserved, will be available to be downloaded and remixed by users in order to promote a creative and playful mode of engagement with them and the history of Clarke’s workshops. In doing so, I aim to highlight Clarke’s videos as processual inputs to be experienced as such, and even extended into new processes. In other words, because Clarke’s Chelsea studio was a playground for adults where videotapes were remixed as part of nightly playbacks, then perhaps an online archive of these workshops should itself be an Internet playground. These materials can be used as a means of making sense of our own playful engagement with new technologies, and how this engagement might extend into the past, in much the same way that Clarke used games to make sense of video in her moment. Allowing people to engage with the history of Clarke’s workshops in this manner provides a richer framework for understanding Clarke’s own playful intentions.