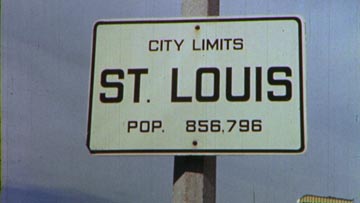

St. Louis population in the 1950s. According to the 2010 census, St. Louis currently has a population of 319,294. Film still from The Pruitt-Igoe Myth documentary.

When the 2010 U.S. Census figures were released in February of this year, many in St. Louis were alarmed. According to census data, the city’s population declined eight percent in the past decade alone. Combined with St. Louis’s current status as the most dangerous city in America—as designated by US News and World Report—this year’s rankings seem to contradict the physical signs and general sentiment that St. Louis is currently on an upward swing.

In the arts in particular, the achievements of this past decade are vast, boasting an impressive lineup of new contemporary art venues, including the internationally renowned Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Boots Contemporary Art Space (which has now closed its doors), and White Flag Projects. Many in the art community—myself included—would like to think that such cultural leaps would register in a quantifiable way. However, the numbers tell a much more complicated story, reminding us that though the arts play an increasingly vital role in enhancing our city’s identity, they alone cannot remedy its larger socioeconomic afflictions.

In America’s art capitals—New York, Los Angeles, Chicago—and perhaps even in other midsize cities such as Kansas City, the identity of an artist’s chosen locale is often peripheral to his or her artistic identity. However, in St. Louis, the city’s identity is so inextricable from the ways in which we live, work, and play that it also seems to seep into our creative practices. Despite the city’s unfavorable socioeconomic indicators, St. Louis celebrates its status as the “Gateway to the West” (a metaphor that later materialized in Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch), as home to the 1904 World’s Fair and Olympic Games, and perhaps most recently, as seat to the “King of Beers.” Less publicized are the city’s alternative art spaces, energetic community organizers, and concentration of print shops, which are threatened to be eclipsed by the notorious social challenges that have persisted throughout most St. Louisan’s lifetimes. In The Twenty-Seventh City, novelist Jonathan Franzen, who grew up in St. Louis, both reinforces and laments upon the city’s diminishing status, asking: “What becomes of a city no living person can remember, of an age whose passing no one survives to regret? Only St. Louis knew. Its fate was sealed within it, its special tragedy special nowhere else.”

If the fate of St. Louis is in fact distinct from other post-industrial cities, so too is the cultural activism that has risen up to redirect the city’s negative image. Perhaps it’s because of its pressing social needs that St. Louis has bred and attracted a unique kind of artist—one like Juan William Chávez or Theaster Gates—whose interest in civic engagement grounds his artistic practice. In a recent conversation with Chávez, founder of Boots Contemporary Art Space, he noted: “If you ask a New York curator what kind of art is being made in St. Louis, they’re going to scratch their heads. However, ask them about the art in Detroit or Kansas City and they’ll be able to provide a description. The art in St. Louis is pluralistic so it’s hard to see the aesthetic right away. But looking at how artists approach and present art, you will start seeing the aesthetic of a social-based practice as a form of cultural activism.”

Much has been written about the use of art as a socioeconomic tool; however, the creative industries in St. Louis differ greatly from the model that urban theorist Richard Florida proposed in the early 2000s. In The Rise of the Creative Class, Florida demonstrated little hesitation in harnessing the arts for economic purposes asserting, “human creativity is the ultimate economic resource.” I could fill page after page with the issues that arise from this line of thinking (which, in fact, I did in my master’s thesis). In short, however, viewing culture purely through green-tinted lenses does both a disservice to artists and to their communities. Often the most successful outcomes of cultural regeneration—including civic pride and stronger communities—are incalculable. Necessitating tangible financial outcomes when supporting the arts puts pressure on them to perform in ways that are often at odds with their internal measurements of success. If handled carefully, the cultural and economic growth of a city may go hand-in-hand. However, in St. Louis, economic development through the arts seems to fall secondary to more pressing needs. Our city still needs to build bridges between neighborhoods divided by both class and race, to improve public education (St. Louis Public Schools were stripped of their accreditation in 2007), and to more fairly distribute resources between city and county. Economic regeneration would perhaps be a happy by-product, but not necessarily a primary objective for cultural activists.

Many hold up Detroit as a beacon of cultural regeneration in the Midwest. In a number of regards, St. Louis shares a history of deindustrialization, segregation, and crime with Detroit. Despite their similarities, St. Louis has not experienced the extent of economic hardship and urban abandonment that Detroit has faced in the past decade alone (for instance, Detroit recorded a 25% population loss in comparison to St. Louis’s 8% loss this decade). Rather than reaching a point of disrepair and starting anew, St. Louis clings to the landmarks, populations, and traditions that continue to linger within city limits. For good or for bad, community organizers contend with the city’s identity, interweaving St. Louis’s historical narrative with visions of its future.

Over the next two weeks, I will look at three separate initiatives that represent different forms of cultural activism taking place in St. Louis today, exploring the inverse relationship between St. Louis’s growing art scene and declining population.

Pingback: Testing the Limits: Cultural Activism in the Gateway City | Art21 Blog « Feeds « Progressive News Feeds