Thea Liberty Nichols: I’ve had the pleasure of curating one of your self-published books into a show I put together a few years ago, and recently you were kind enough to have me over for a studio visit where we got to rifle through your flat file. Can you detail for us your process of taking a work from creation through to production— whether it’s an animation, inking a comic, printmaking, or book-binding— and on out into the world, either through screenings, publishing, or what-have-you?

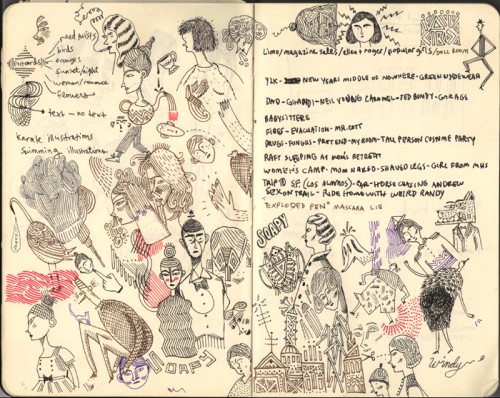

Lilli Carré: For whichever medium I end up choosing for a project, I usually start with scribblings in my sketchbooks and loose little notes and ideas all over the pages, which end up looking something like this:

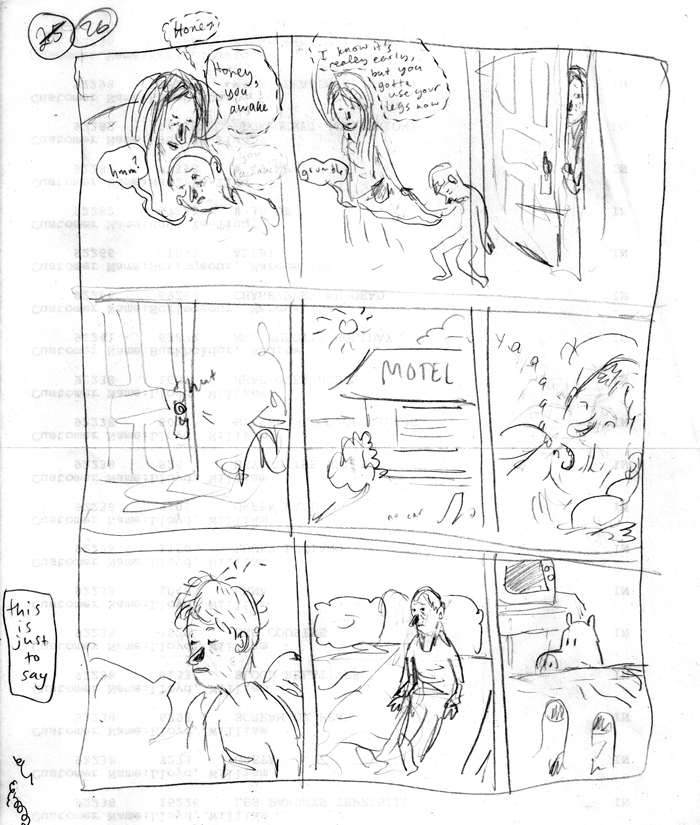

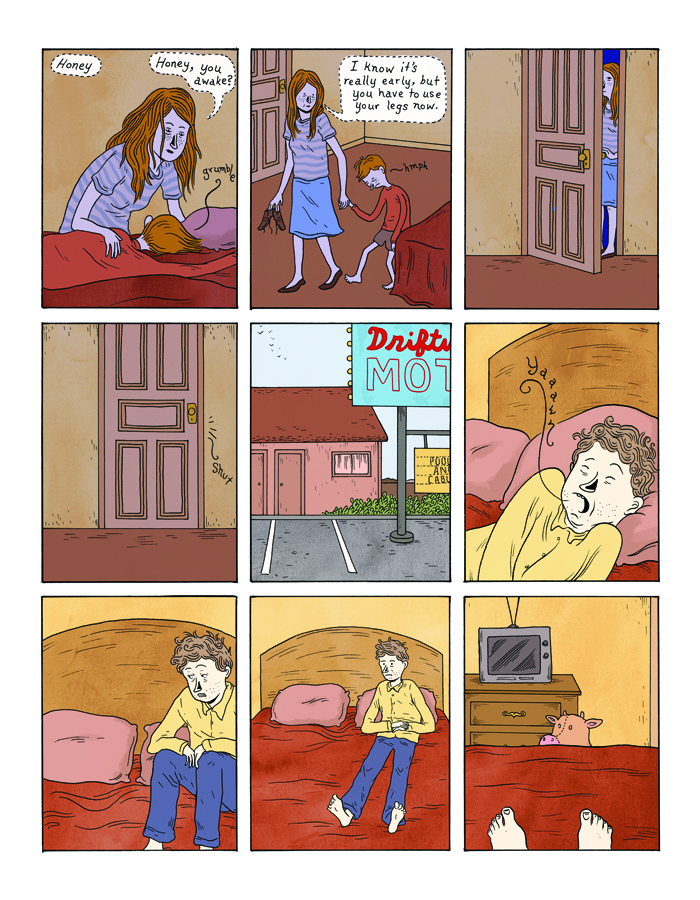

When I work on a comic, I’ll start with these ideas and start to form a narrative thread, and from there I start making thumbnail storyboards for how I’m going to draw and structure the final comic. Here’s one of my loose storyboards for a page from my story “The Carnival”:

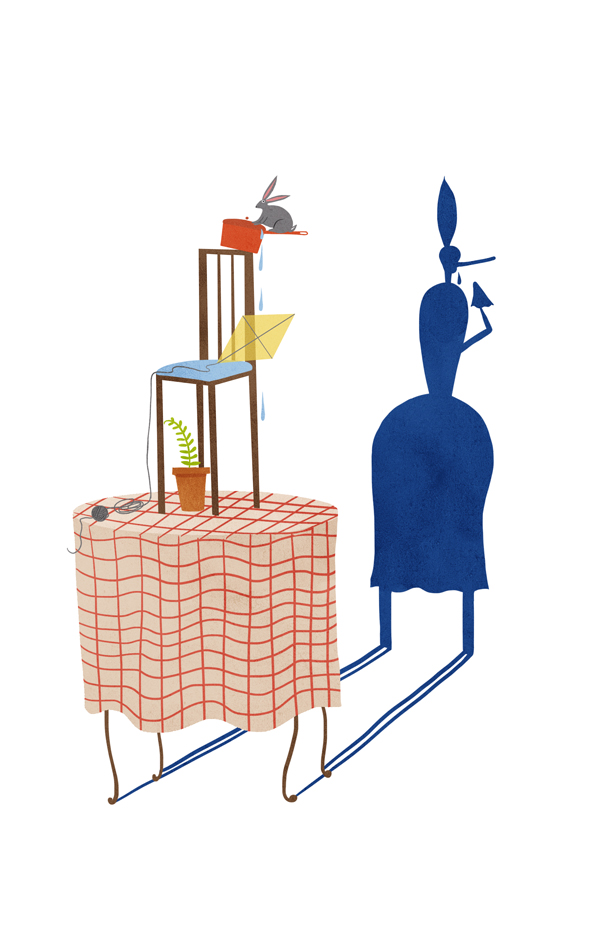

and here’s the final page:

When I work on animation or printmaking, it’s sometimes carefully plotted out, but lately I’ve been enjoying working much more intuitively in these forms. For animation, I’ll just start drawing frames, maybe starting with a particular little motion or simple scene and then build on it as I go. This whole animation Head Garden was made in this way— just starting with the idea of a man losing his head and drawing straight-ahead as I went.

When I work on animation or printmaking, it’s sometimes carefully plotted out, but lately I’ve been enjoying working much more intuitively in these forms. For animation, I’ll just start drawing frames, maybe starting with a particular little motion or simple scene and then build on it as I go. This whole animation Head Garden was made in this way— just starting with the idea of a man losing his head and drawing straight-ahead as I went.

I’ll make animations and prints most often just for myself, and I post most of my film work online but also sometimes send pieces out to experimental film and animation festivals that I like. For my comic work, I will either make a story for a specific anthology or to put out as a book, either with a publisher or as a self-published comic. It’s nice being able to finish a comic story and then immediately put it out as a self-published little book. It’s very cheap to do this (silkscreen printing, Xerox, etc.) and there are still lots of fun ways to get into designing these. I’ll trade them or sell them at comic book shops or at alternative comics fests. Right now, I’m working on putting together a larger book that will collect my self-published comics as well as my contributions to anthologies like MOME and Glomp and my strips that ran in The Believer magazine.

TLN: I know you studied animation and have several animated films under your belt, but there’s a sense to the pacing and a sensitivity to sound that I also recognize in your 2-D comics and illustrated work. Can you tell us more about how these media interrelate and inform each other? Do ideas ever evolve from one medium to another, or beg a certain type of medium from the onset?

LC: I frequently switch back and forth between working on comics and animation. Sometimes it’s nice to be able to work with pages, where I can really focus on the details and nuances from one panel to the next, and an overall page composition. After I’ve been working on something like that for a while, it feels very freeing to switch to working on an animation, and draw 12 drawings for every second of film. It becomes much looser in terms of each individual drawing, and is more about the overall feel and movement. So I’m constantly switching between the two mediums, and this does result in some crossover. I have aimed to create an ambience in some of my comics based on rhythm and written sound, trying to create the same feeling of mood and pace that you might experience when watching a film. I also carry some of the narrative themes that I develop in my comics over to my animation work, where I play with them in a more loose and abstract way. I have had little ideas for animations which have ended up being worked into comics and vice versa.

TLN: I’m just getting more familiar with the growing network of self-publishers and (mini-) comic makers in Chicago, of whom I know you’re colleagues with and already connected to. Can you tell us more about the Trubble Club and what your involvement with the group has been to date? In general, how do those types of collective making and publishing activities expand or alter the art-making practice you’ve already developed?

LC: Chicago is a great city for alternative comics, and there are a lot of cartoonists living here. A couple years ago, a handful of us started meeting up on occasion and drawing collaborative short comics together, usually very goofy ones, and eventually this group was dubbed “Trubble Club.” Since comics can be a very solitary endeavor, and Chicago winters are usually pretty harsh and isolating as well, it’s nice to have a group of people to occasionally draw with and talk shop about comics and stories and particular technical stuff like pen nibs and such. I don’t go too often, but when I do it’s a fun time. I think the most helpful part of group drawing like this is to just put aside the rigidity one might have with his own work and just go for a ridiculous idea off the top of his head and let out some drawin’ steam. It definitely yields some very bizarre comics!

Lilli Carré grew up in Los Angeles and currently lives in Chicago, where she works as an animator, cartoonist, and illustrator. Her animated films have shown in festivals throughout the US and abroad, including the Sundance Film Festival and the Aurora Film Festival. Last year, she co-founded the Eyeworks Festival of Experimental Animation in Chicago and is working on plans for this year’s fest. She is the author of the graphic novels, “Tales of Woodsman Pete,” “The Lagoon,” “Nine Ways to Disappear,” and “The Fir Tree,” and has recently contributed comics to The Believer magazine, Mome, “Best American Comics 2010,” and “Best American Nonrequired Reading 2010.”

All images courtesy of the artist.