Between these two covers is artist Vince Leo’s Nobody Remembers Timetable Project, commissioned in 1990 by the now-defunct National Association of Artists Organizations (downloadable through Gregory Sholette’s Dark Matter archive). Starting in 1905 and ending in 1990, the timeline catalogs an idiosyncratic range of cultural and political milestones. For instance, in 1912: the U.S. invaded Nicaragua, Man Ray attended art classes at the Ferrer Center, and the IWW lead the successful “Bread and Roses” textile workers strike in Lawrence, MA. I wish I could have been at some of these events as a fly on the wall. Like the Neighborhood Art Programs National Organizing Committee (NAPNOC), formed in 1976 at an NEA-funded retreat attended by two dozen community artists at a United Auto Workers’ center in Black Lake, MI. Or in 1977, when NAME, a seminal alternative art space in Chicago, hosted a Midwestern Alternative Spaces Conference.

I am in the midst of organizing what we hope will be a like-minded gathering to these earlier efforts, the Hand in Glove conference at threewalls, which will take place this October in Chicago. Designed for both the artists who participate in these spaces and the organizers, administrators, and curators who run them, Hand in Glove is for anyone and everyone who engages artist-run culture to talk about its past, its current manifestations, and its potential futures. It’s a four day event of national scope that will address the state of self-organized, noncommercial and artist-run spaces, publications, residencies, and a variety of other projects happening at the grass-roots level. Conversations will range from sustainability to funding to unconventional organizing models, as well as the kind of creative administrative strategies people are using to stay open.

In Chicago, we talk a lot about the unique arts organizing resources of our region, such as the collaborative spirit that exists between artist-run spaces and small-scale non-profits, all the way up to some institutions. There’s a lot of opportunity here; people are genuinely willing to collaborate and pay attention to each other’s experiments and contribute to an active dialogue about what constitutes a vibrant art scene. It seems appropriate that the Hand in Glove conference is being organized in the Midwest. Perhaps that’s due to the fact that Chicagoans, as members of the self-proclaimed “city that works,” are so invested in providing opportunities for each other. There is an implicit understanding that no one is going to provide them for us.

The Midwest is also a good setting because often the narrative around seminal alternative spaces is focused on New York. That may be because a lot of them are still around and thriving. The beginnings of places like 112 Greene St (now White Columns) or Artists Space are more familiar to me and easier to find out about than NAME Gallery or other Midwestern radical arts organizations that arose at the same time. That same feeling goes for having access to the detailed history of the Art Workers Coalition, but knowing little about the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, enacted by Congress in 1973, that provided federal employment to chronically unemployed groups including artists, in addition to seed money for alternative spaces to begin paying their staff. One history is perhaps more colorful and the other more pragmatic, but the point is that these multiple trajectories inform each other, and provide the broader picture and history that is needed to build mutually supportive arts infrastructures today. I often think about how to bring these parallel perspectives together, meaning arts organizing from the position of the artist, and arts organizing from the position of the administrator.

The goal of the conference is to launch a still-nascent idea: a national Alliance of Independent Arts Organizers that would provide resources, professional development, and mentoring opportunities for people that do this kind of work. It’s obvious that there’s a considerable distance between what the National Association for Artists Organizations did in its heyday–provide a support network to organizations that then in turn supported experimental and challenging art activity—and what is possible today, when most people starting an artist-run space don’t have much hope of ever turning it into a sustainable enterprise. Right now, there is no ambitious national program to support nonprofits and noncommercial arts organizations that has much currency with the general public. These ventures are usually paid out of pocket, which obviously limits who can participate. Nevertheless, artist-driven supportive infrastructures are popping up locally all over the place, in Detroit, in Kansas City, in Baltimore, in Minneapolis, in Chicago.

An alliance such as this does not intend to let the government off the hook, or position this kind of practice in purely business terms, where we teach each other how to professionalize. Rather, it is implicitly understood that artist-run activity at the grassroots level makes for a better local culture; yet advocacy groups do not yet exist that can address the specific needs of those who are operating from that position, or create avenues for participation at the policy level. We would like to network with each other to find larger solutions as well as discuss the ethics of starting small and keeping small, the compromises of becoming bigger, and the inventive problem-solving that keeps independent culture alive and well. This is a creative conversation that should be collectively authored amongst artists and their support structures, taking into account the people and the economies that make things happen.

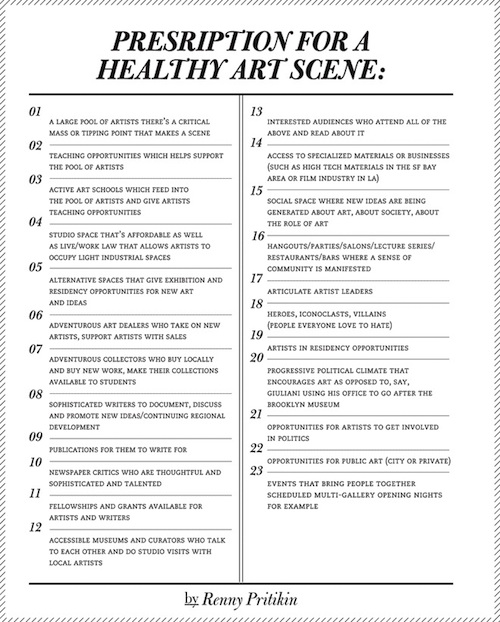

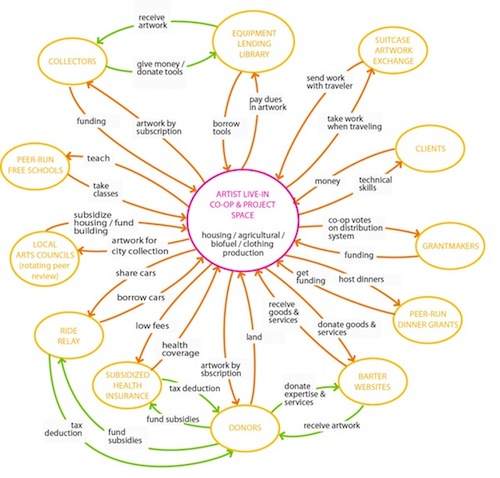

A healthy arts ecosystem depends on the energy of temporary projects that deliberately resist becoming permanent, the commitment and dedication of small non-profits, and openness and exchange with more traditional art institutions. To scale down from the national picture, Renny Pritikin, the founder of the National Association for Artists Organizations, recently wrote a prescription for how that scene might function on a local level (illustrated above, and published in Proximity Magazine‘s July 2009 issue). And then on the scale of individual spaces, Elysa Lozano, an artist in Brooklyn, recently presented her own proposal as part of the weekly public Skype chats that Philadelphia’s basekamp holds on the subject of “plausible artworlds,” whose project is “to collect and share knowledge about alternative models of creative practice.” Lozano is the Director of Autonomous Organization, an art practice as a not-for-profit organization, whose projects are subject to the oversight of a board of directors. Her work, 1:1 Scale Model for a New Art Economy, is a two-part initiative: The first part is a series of summits with people who work in different roles in visual arts to ask them what their ideal art economy would look like. The second is to make a 1:1 scale model from the evolving diagram that emerges from these meetings.

I can think of multiple instances of these kinds of localized efforts today, such as The Philadelphia Lendry, an experimental membership library of of art, material objects, cultural ephemera, creative services and assorted oddities; or art subscription efforts like The Present Group or Alula Editions in the Bay Area; or funding initiatives like the Critical Fierceness grant by Chances Dances in Chicago; or the Public School in Los Angeles; or experimental residencies like the Summer Forum for Inquiry and Exchange, which will take place next year in New Harmony, Indiana, a former socialist community. Lately I’ve been in a flurry of activity researching these organizations for threewalls’ upcoming publication, PHONEBOOK 3, a national directory of independent art spaces, residency programs, event series, and resources like free schools, micro-grants, and libraries. In looking at all this work popping up that is mindfully building communities, it’s evident that many artists don’t enter the art world today expecting to make a living at it. Rather, they seek that place where they feel they belong, and look for others with whom to make that place a reality. At Hand in Glove, these initiatives will be in conversation with longstanding institutions like Southern Exposure and Franklin Furnace Archive to capture some of that inter-generational wisdom. And hopefully organizing this kind of conference outside the boundaries of academia or a pre-existing professional development organization will open up new ways of collaborating. The question is, what happens when we scale up?