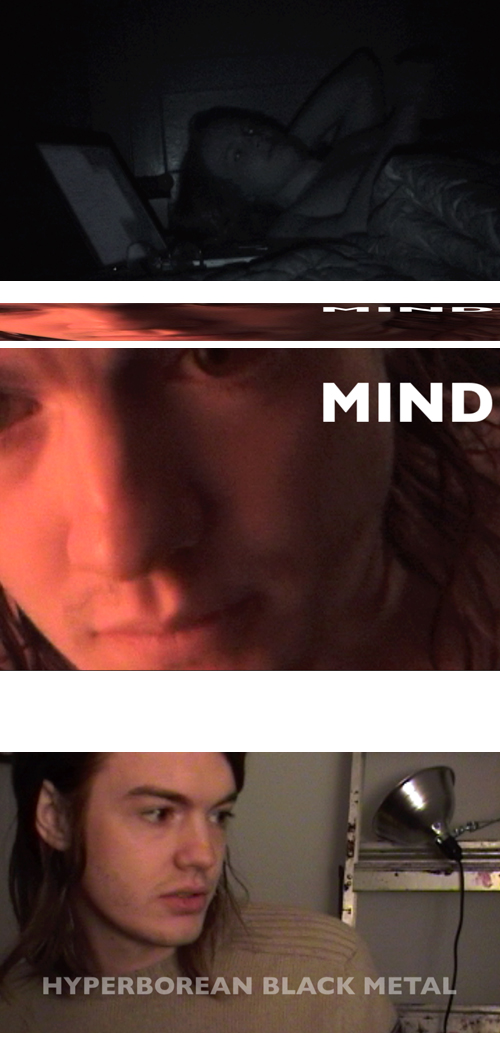

Hunter Hunt-Hendrix presenting “Transcendental Black Metal” at Denmark National Art Gallery, 2011 (image gleaned from “Black Sofie,” via the Facebook).

Hunter Hunt-Hendrix’s work first caught my attention a year and a half ago when I came across his manifesto “Transcendental Black Metal” in Hideous Gnosis, a published compendium of the papers delivered at the 2009 Black Metal Theory Symposium. Since its inception, this manifesto—which explores European and American Black Metal music subcultures, philosophy, and musicology—has sparked a lot of friction. This reaction is due, in part, to Hunter’s unique definition of Black Metal and his amalgamation of ideas that typically have a nearly allergic response to one another. But, prominently, the most aggressive reactions have been incited because Hunter is not only delivering papers at alternative academic affairs, he is also actively redefining previous notions of the underground extreme music subgenre Black Metal as the frontman of the American Black Metal band Liturgy.

I first contacted Hunter because I was intrigued by his manifesto, ecstatic that his interpretation of Black Metal offered an account of Transcendence over the Nihilism widely prescribed to the subgenre, and inspired when I finally caught a Liturgy concert live. Since I began my art historical and curatorial research in Black Metal and contemporary art (the subject of my graduate thesis project at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago) I have gleaned scores of artists whose interest in Black Metal has drastically influenced their studio practice, yet it wasn’t until I joined Hunter for a three-mile-long walk from Chicago’s West Loop arts district to the Empty Bottle concert venue this Spring that I realized the relationship between Black Metal and contemporary art was much closer than I had previously conceived. Hunter was interacting with many of the same theories that my favorite artists were, traveling from Black Metal towards studio art… meeting at the same trans-modal stage.

This interview builds off of previous interviews Hunter has given with Elodie Lesourd for C.S. Journal and Scott Indrisek for Artinfo to explore the performances of “Transcendental Black Metal” he presented earlier this year at both MoMA and the Danish National Art Gallery, and his video project “Genesis Caul.”

Amelia Ishmael: Although your work with Liturgy [Tyler Dusenbury, Greg Fox, and Bernard Gann] is probably most widely recognized, you have also presented solo art performances, such as one held at MoMA in July earlier this year. How has your approach to Black Metal provoked these projects?

Hunter Hunt-Hendrix: I’d like to think that at the institutional level the divisions between the networks supporting all the different kinds of creative activity out there are evaporating—not just art and black metal. That said, there is clearly a particular resonance between the two. When I started Liturgy I was extremely frustrated, almost desperately frustrated by the realization that at a certain point I’d have to choose a “world” to deposit what I was making. I hate these “worlds” like the d.i.y. independent music scene, the metal scene, the art world, “serious music,” the so-called indie rock music industry, philosophy, critical theory. I was never able to compromise and choose a single path, so it’s been a struggle. We’ve always been half-deposited in a few different worlds. It has been very uncomfortable, because I always end up with the sense of being half-recognized, as an intriguing outsider and/or a charlatan. At the Hideous Gnosis symposium I was the only musician to present a paper, which was the “Transcendental Black Metal” lecture. The presentation at MoMA of the same lecture was a meant to be a cross between performance art, ritual and pedagogy, in homage to Joseph Beuys, which is why I wanted to do it next to his “Eurasia Siberian Symphony” (1963) sculpture. I presented it as a Powerpoint with laser pointer along with chanting and candles at the Danish National Art Gallery just a week ago. It was pretty cool to actually do it in Scandinavia. I get off on infiltrating art institutions; these are concrete ways of crossing boundaries.

But the real point is that—and I’ll just disregard how cliche’d this sounds as it is an eternal truth—true art is essentially life, it is an awareness and attunement to a certain divine creative flow which is always there, and ultimately it is a question of ethics and of living a true life. Now maybe it happens that this was really driven home within the artworld long ago, especially by Fluxus and by Beuys and so on. People talk about Fluxus like it is a movement from the past, but they’re wrong. It’s a mistake to categorize something like that as a movement that ended, say, when Maciunas died. It is still going on, but it no longer needs the cradle of the “artworld” to incubate it.

https://vimeo.com/27229724

AI: Can you tell me more about the piece at MoMA? Was it a hybrid between the type of vocal work that you perform as Liturgy and the spoken (?) Black Metal Theory lecture?

HHH: We performed a full Liturgy set in the cinema beneath the Beuys video Eurasienstab (1967/8). The choice of video was made by Jutta Koether, not me, based on my interest in Beuys. Then I presented the same lecture that I’d presented at the Hideous Gnosis theory symposium, except that I drew the diagrams on an easel pad and manipulated my voice so that parts of it were quite difficult to understand.

AI: This venue is much different from the dark concert venues/bars that I’ve seen Liturgy at previously. Have you performed in this type of white-walled space before? Does the atmosphere change how your work is performed and/or how it’s intended to be received?

HHH: I’ve done a fair amount of performing within gallery spaces. Never the full band, because the volume freaks people out too much. The atmosphere doesn’t change anything about the performance or the intentions, no.

AI: We’ve talked a little bit before about Wagner’s concept of the “Total Work of Art” and the interest in breaking down the separations between art and life. One of my favorite quotes from this text is his proposal: “for Art to operate on Life, she must be herself the blossom of a natural culture, i.e., such an one as has grown up from below, for she can never hope to rain down on culture from above.” With references to both the d.i.y. independent music scene and avant-garde(?) experimental art and sound, your work seems to draw from above and below, converging in a type of potential space existing between these two distinctions. Would you agree?

HHH: I certainly agree that Liturgy and my para-Liturgy work are influenced both from what is known as fine art and what is known as independent culture. But as far as the quotation goes… Wagner’s context is very different from ours. I think for Wagner “culture” is synonymous with “high culture.” I’m much more interested in the Beuysian expanded Gesamtkunstwerk than the ordinary Wagnerian one.

AI: What draws you to Beuys’s work specifically?

I like Beuys’s unflinching fusion of art, ethics, politics, pedagogy and spirituality for one. And his utter lack of interest in things like institutional critique and so on is a relief. There is this naivete in his work… old fashioned use of symbolism, the desire to save the world by means of art, and to live every moment as art, to create political institutions as art. And I like his willingness to be a dilettante, to be constantly stepping outside the boundaries of what he’s expected to do as an artist. He had his own theory of money, for example. He commented on nothing, critiqued nothing, he just wanted to activate people.

AI: Can you tell me about your video project Genesis Caul?

HHH: The Genesis Caul video is a document of the process of composing the Transcendental Black Metal essay. I wanted to present the Coagulation of an Idea, from the starting point of existing as a strong inspiration, almost like a tidal wave, with no actual form or content, through all the hiccups, flagellations, awaitings, revelations, revisions, slips and so on and ending with System of Ideas which are partitioned, murdering the inspiration by fulfilling it…. I also wanted to be really honest about the oscillation between ordinary subjectivity and creative work. Ultimately it is a presentation of Creation.

AI: In your interview with artist Elodie Lesourd you mentioned a new recording project exploring the “Arkwork.” What is this concept and how are you exploring it sonically and/or through other modalities?

HHH: “Arkwork” is a term that came to me and that I find to be very beautiful and mysterious. It touches upon this belief I have that any kind of art or culture doesn’t count unless it is somehow more than what it is. Art is worthless unless it is more than art. There is a dimension of struggle, ethics, absorption of and by chaos, stepping forward into the darkness. I am not exploring it sonically at all. It describes the persistence of maintaining this connection and producing in spite of the detritus everywhere. These days Henry Miller’s books are like my bible. The Arkwork is like The Rosy Crucifixion. It is bearing a cross because somehow it is the right thing to do. Not something that ends up being represented, but rather the process of continuing to follow a creative urge to the end, because of a wound that isn’t really a wound. Another aspect of the Arkwork is raising the child, so to speak, after it has been born, letting it go and seeing how it ricochets around in the world. I very much want to incorporate reactions to Liturgy into the Liturgy project. And there have been very strong reactions, especially negative.

AI: One of the things that captivates me about the video work is its intentional choppiness or rawness, as though you are uttering or creating a space where the Transcendental Black Metal essay could occur. I can’t help but be reminded of Nietzsche’s three metamorphoses of the spirit… Is there a linear trajectory here? Are the “Genesis Caul” and Arkwork concepts connected as part of a larger project?

HHH: The larger project is an opera that will be called “01010n” in honor of the character of Ololon in Blake’s penultimate illuminated poem, “Milton.” Everything leads up to “01010n,” but I really don’t know what form it will take. It is interesting that you mention the three metamorphoses of the spirit because that’s loosely how I’m separating the three acts of the opera. For me—and I think for a lot of people—the creative process is very, very, discontinuous, while at the same time there is an overall linear trajectory. That’s part of the meaning of the Genesis Caul video—it documents the development of a very tightly composed essay, but the whole process is throbbing and stuttering and moments of forgetting, giving up, and so on.

AI: Thank you Hunter!