For years, Jeff Koons (Season 5 Episode “Fantasy”) has been controversially appropriating dime store trinkets — kitschy souvenirs and ad campaigns. If it wasn’t for Koons, these once popular items would clog beaches and landfills as forgotten castaways of passing fancy. Koons “rescues” them, plucking them from the lowly world of dollar store giveaway bins and subway billboards, in order to reproduce them on a larger-than-life scale. With a new pedigree, the artifacts are worth thousands, if not millions of dollars. They ooze with a disposable, American decadence — a “Nouveau Versailles” aesthetic — critiquing the culture in which they were conceived almost as if by accident. “Balloon Dog is full of everything except gods, a de-deified sculpture that radiates irony and Eros. It’s an updated version of Duchamp’s urinal,” wrote Jerry Saltz in New York Magazine in July 2008. His work Made in Heaven represents the final fruit of Koon’s ongoing ironical exploration.

Where Warhol employed the soup can, Koons took the toaster, the vacuum cleaner, and the basketball. Rather than silk screen these objects (a medium with its own associative history of democratic dissemination), Koons set the objects in custom vitrines, enhancing the already emanating auras of convenience, luxury, and free time – conquests of an American life that indicate success. He aestheticized the design of everyday objects, and like a knight in shining armor, (think of Richard Gere pulling down the street in a limousine to fetch Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman), redressed the debauch of everyday in expensive clothes, toured it around the country, and made a fortune. He mirrors the exploitation of entrepreneurial practice in his own artistic endeavors, highlighting the erotic potential of inanimate objects so that we, the audience, begin to salivate. Shortly after his first exhibit, Koons began recreating tchotchkes. He made towering reproductions in factories with a team of employees. Videos of the artist at work feature Koons with a hard hat and a clipboard, pointing directions to a team of laborers. His art became a comment on the manufacturing business and has continued since.

There has always been a sardonic, if not nihilistic flair to his work. For all we know he is making fun of us, mocking our feeble efforts to maintain a cool distance from the uglier parts of consumer culture, pointing out the terrible truth behind exploitative ad campaigns and commercial structures. By reproducing and marketing lowbrow detritus to the cultural elite, Koons demonstrates the undeniable appeal in trashy, hedonistic totems. Cuddly kittens, balloon animals and Popples are irresistible. Still, Koons manages to remain ironically distant. It is unclear whether he believes in his homage to bubblegum, or if he makes his work out of critical spite. The taboos he picks up on – the more than dubious representation of women in his work, for instance (think of the Pink Panther hugging the busty blonde, which sold for 16.8 million dollars in 2011) – are not originated by Koons, but by us and our culture. Koons implicates everyone while profiting himself. Which is why Made in Heaven seems like such an excellent conceptual climax: he illustrates a cultural fantasy, propagating the power structures therein, indulging in a non-literal, plastic, commercial body. In this case, however, his hands are dirty. He offers his own body for public consumption.

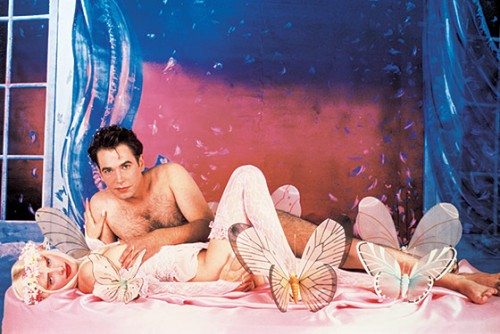

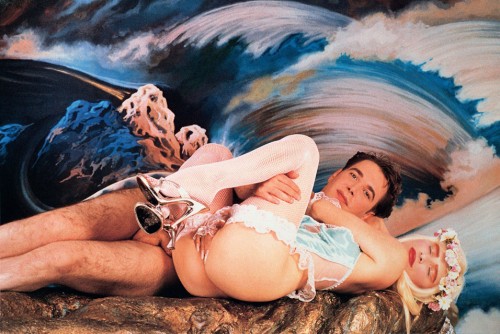

The blatant point made in this work still elicits disgust. When exhibited in museums, the work is sequestered in smaller, partitioned rooms with signage that warns against their content. We are, after all, squeamish about sex. Made in Heaven taps into an almost ancient battle: how to define the distinction between pornography and art? In this particular case, that distinction is deliberately conflated. One might supposed the series is art because it is pornography: a specifically staged, anesthetized project about copulation. A reproduction of porn that nevertheless fulfills its pornographic function: penetration is visible. Body fluids are exchanged. Yet, like the rest of Koons’s work, Made in Heaven neither celebrates nor condemns pornography. Instead it reflects the cultural feelings around it, the artifice and industry of porn. The bodies in this work, like the bodies in pornography, are highly anesthetized, no different from his Michael Jackson sculpture and probably as misleading as one of his balloon rabbits. Ultimately this display of intentional and highly controlled sexuality troubles the function of a museum, highlighting also Cicciolina’s troubling insistence on participating in other echelons of society, namely politics.

Koons’ co-star and (now) ex-wife, Anna Ilona Staller was born in 1951 in Hungary. After immigrating to Italy, she appeared in her first hardcore film in 1983. By this time she had already adopted her stage name, Cicciolina (or “Cuddles”), and boasted that hers were the first breasts to be shown on public Italian television; she claims to have transformed rules and regulations about nudity. Indeed, she is particularly famous for wielding a public (and successful) sexuality. In 1987, 20,000 people hand-wrote her name onto a ballot after her strip-tease political campaign. She won the election. Once assuming her seat, she maintained a flagrantly sexual public persona (completing one adult film during her term) while infiltrating the boy’s club of politics. Women were not permitted to run for office until after World War II and, by the time Cicciolina took office only 10 percent of total parliamentary seats were held by women. The way in which she chose to wield power was, for many, a national embarrassment, a sore spot that has again come to light in recent events, as the Italian public is outraged about paying her annual pension.

Cicciolina’s public life is centered on an exploitation of self that Koons highlights in Made in Heaven. She leverages her body to gain access to power, becoming another icon, like Michael Jackson or Snoopy, for Koons to appropriate. Koons, on the other hand becomes (for her) another artistic director. Together they recall inarguable statistics about the sexual life of our times and its flanking societal moirés. Entrenched in this are additional issues of gender equality, commercial exploitation and consumerism. Pornography is still very much a taboo subject. Yet, 12% of all websites are pornographic. There are around 68 million search engine queries for porn each day (Online MBA) and the annual revenue derived from the porn industry is staggering. Still, the action of porn remains in the shadows, far from the action of a family dinner (interestingly enough, Thanksgiving has the lowest porn viewing of any other day in the year). Additionally, the rights of women who work in the sex industry are wildly controversial; it’s a subject with deep fissures within and without feminism: are these women liberated or exploited? Made in Heaven calls forth all of these issues. Here, Koons is a distraction: a red herring. Because, with him in mind, the work fulfills a cliché fantasy: the final payoff of capitalist success.

The show came together in 1989, when Koons erected a series of billboards featuring himself and then-wife Cicciolina. They met on the set for this project. She flirted with him. They got married. It seemed hilarious, like something out of a bizarre sitcom, as though they were continuing a farcical performance into real-life, collapsing the edges between artistic persona and private biography. He may or may not have learned Italian but they did have a child — suddenly the arrangement was not funny at all. They had to entertain the doldrums of day-to-day life: a banality that resists superficial engagement. Unlike all of his previous work, Koons implicates himself in Made in Heaven, not only because he photographs a series of pornographic photos with Cicciolina, but because what originally seemed like a masquerade of persona became an ironic (and highly public) catastrophe involving a 14-year custody battle.

In the end, Cicciolina defies simple objectification. She somehow surpasses Koons in her impression, growing ever more interesting as she grows less and less triumphant. She didn’t get custody (though she continues to raise their son); she was almost sent to jail, and now the country wants to protest her pension — a pension awarded every other individual who has held political office (many of whom were dubious themselves) because of her sexual behavior. Her public sexuality, with its own origins in 60’s feminism (where free love was equivalent to sexual equality) strains towards something positive. The failure of Cicciolina’s postulate is likely one of the things that makes her ultimately so sympathetic. She is quoted saying, mournfully, “I did what I did, and I’m happy about it. But all the men around me exploited my sexy nature to take me to bed or to make money. As if sexual libertinism inevitably implied the absence of love and of sensitivity. I am a very romantic person, but nobody ever realised it….” (Belfast Telegraph, May 2008).

Art Historian Dr. Thomas Zaunschirm once referred to Duchamp’s readymade as “a willing girl,” and Koons seemed to take this metaphor literally. It was not enough for him to find the readymade in a static object; he applied that same fetishized appropriation to a woman, specifically one whose public image was inextricable from her persona as a porn star. Everything about his project tries to reduce her to that one punch line. Perhaps that, most of all, is why Made in Heaven remains so unsettling — because the mechanism by which we are exploited, exploit others, and exploit ourselves every day becomes transparent and aestheticized. Made in Heaven is almost like a theoretical proof, demonstrating the finitude of irony — it cannot go on forever, and Cicciolina resists the bondage of her identity.

Caroline Picard is a regular contributor to the column Centerfield: Art in the Middle with Bad at Sports. She is Senior Editor of Green Lantern Press in Chicago, IL.

Pingback: Cicciolina & Jeff Koons | The Lantern Daily