“A local dancer,” is what arts reporter Jori Finkel called Yvonne Rainer in an LA Times article dated November 12 (though a concurrent blog post by Finkel called Rainer “legendary,” a more accurate description of the filmmaker and performer, who worked with Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham). Finkel was reporting on this year’s MOCA gala, an annual fundraiser known for featuring the work of some sort of art world star — last year’s artist was Doug Aiken, and the year before Francesco Vezzoli with help from Lady Gaga — at an exclusive, high-priced dinner for patrons. This year, Marina Abramović, fresh out of her MoMA retrospective, helmed the gala, planning an extravaganza with human centerpieces and naked-lady cakes.

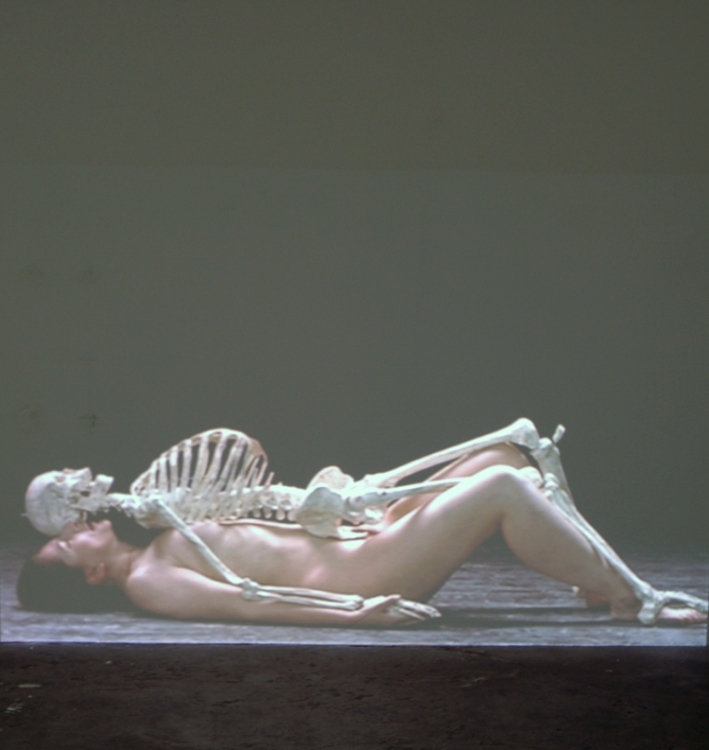

Finkel referred to Abramović as a “Yugoslavian-born, New York performance artist,” more cosmopolitan than “local dancer” though not terribly inflated, given that Abramović has been called, and has apparently called herself, the grandmother of performance art. Controversy erupted after Abramović hosted auditions to cast those human centerpieces, particularly the stoic heads that would turn slowly around in the middle of each table. Performers would sit on Lazy Susans below the tables and would not be able to get up or use the restroom during the three hour event. A handful of female performers would lay flat on their backs in the middle of a few special tables, naked, legs far enough apart to see what was between, with skeletons on top of them (a re-imagining of one of Abramović’s former projects, Nude with Skeleton). The performers would be paid $150 and given a year-long MOCA membership. Rainer heard about these auditions, apparently from an artist who had participated, and responded angrily. The letter she sent to MOCA director Jeffrey Deitch has, by this time, circulated widely. She accused the museum of economic exploitation — compensation was not enough — and also, in what may have been the most memorable part, wrote that the performance was

reminiscent of “Salo,” Pasolini’s controversial film of 1975 that dealt with sadism and sexual abuse of a group of adolescents at the hands of a bunch of post-war fascists. Reluctant as I am to dignify Abramović by mentioning Pasolini in the same breath, the latter at least had a socially credible justification tied to the cause of anti-fascism. Abramović and MOCA have no such credibility. . . .

More back and forth ensued, Deitch and Abramović invited Rainer to attend the ongoing audition, a number of arts blogs weighed in, among them ArtFag City, Hyperallergic, and ArtCritical. Of course, most “critics” did not attend the gala, certainly Rainer did not. I didn’t either. It’s an odd position to be in: criticizing art you didn’t see at an institution that desperately needs funding and acquires it the way many cultural institutions do, by marketing its exclusivity and creating highbrow spectacle.

Even if I’m cagey about taking a stance on the gala itself, I have no qualms about saying that, of the two 20th century art matrons, it’s Rainer, the one who would likely cringe at even being called a matron, I’d trust to do the ethical thing. This isn’t to suggest that Abramović is an unethical artist, just that for Rainer integrity — what it is, how to maintain it — has more or less been the subject of her now 50-year practice. She wanted to give the “everyday body,” not an idealized body, a place in dance, which led her to reject the minimalism of John Cage that she had initially embraced. Then, afraid dance wasn’t allowing her to explore her feminism and the emotional experience of being human in an honest-enough way, she began film-making in the 1970s. Her whole career reads like that — rejections, revisions, new directions, all in hopes of figuring out how to be an artist who respects real people’s experience.

What’s bothered me most about the MOCA gala debacle is the thought that Rainer would likely never be chosen to orchestrate an event like that. Why not? Granted, much of Rainer’s work is more abstract than Abramović’s, less visceral; there are no naked bodies in doorways, staring contests, or skeletons.

But she’s done some exquisitely accessible projects, like Assisted Living, based off photographs from the New York Times sports section, or her piece in the 2008 California Biennial, where dancers wore bright red sneakers and moved loosely and unpretentiously in a way that made dance as easy and awkward as schoolyard play. If it’s true that Rainer’s just not glamorous enough or that she can’t generate enough hype or that she wouldn’t attract donors, we should have better taste.

Note: If you’re in L.A., consider attending the panel that Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) is hosting Saturday:

Abramović, Rainer, gala theater & performance art politics: a public forum

6522 Hollywood Blvd.; Sat., Dec. 17, 1-4 p.m.

Pingback: Gastro-Vision | It Was a Sweet Year | Art21 Blog