I started the night in the corner, watching a girl in a sequined dress hover over the hors d’oeuvres and thinking about the inherent awkwardness of company holiday parties. After one glass of wine I was standing, listening to a woman from the education department sing a karaoke version of “Barbie Girl.” By my second glass, I was smoking Marlboro Lights outside with the rest of my department. After three glasses, I was doling out relationship advice to someone—I can’t remember whom. What happened after four and five is anyone’s guess, for that is when my memory departed and the night became a cosmos of faces, sentences, and movement; that is when I yelled freely, introduced myself to strangers, and delivered random accusations. Though the party ended at 9 p.m., I found myself on the midnight BART train home, sitting beside a man whom I kept calling the wrong name. At 2 a.m. I slept on my feet in the hallway outside my apartment as a locksmith jimmied my front door. At some point I had misplaced my keys, and that loss seems an apt metaphor for the other thing I lost that evening: namely a sense of narrative consistency.

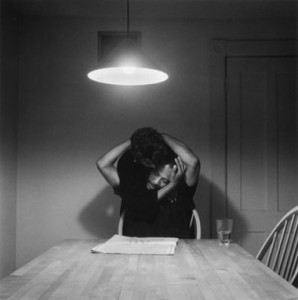

We remember sober life as a sequence of consecutive images, costumes and personalities intact from scene to scene. Occasionally our memory lapses, but context and routine allow us to fill in the missing information. I think of Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table Series (1989–1990), in which the table serves as a locus uniting disparate scenes. The static motif anchors the images and allows us to construct a story through them: a man stands behind a woman sitting in the chair; the two play cards; she feeds him; she sits to the side as he reads a newspaper; she stands in the shadow as he reads; the two embrace. In the next image she is seated at the table alone, her head bowed. A bottle of wine is by her side, and the telephone is in the foreground. Though we do not see the man leaving, we can infer his departure. This is how we build narrative, reading discrete moments as a continuous flow, creating meaning from their progression and projecting our assumptions onto the omissions. There is the occasional unexpected event—the trauma of death or a catastrophic event—but for the most part our experiences remain coherent, legible.

Carrie Mae Weems. From Kitchen Table Series, 1989–90. Set of 20 gelatin-silver prints, 28 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches each. © Carrie Mae Weems.

Carrie Mae Weems. From Kitchen Table Series, 1989–90. Set of 20 gelatin-silver prints, 28 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches each. © Carrie Mae Weems.

Carrie Mae Weems. From Kitchen Table Series, 1989–90. Set of 20 gelatin-silver prints, 28 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches each. © Carrie Mae Weems.

If sober life is intelligible in this way, a mostly linear affair, then drunk life is a montage—isolated images set apart, illogical sequences, dramatic juxtapositions. Key transitions are removed, replaced only by allusive and mysterious gaps. I think of Tacita Dean’s Floh (2001), the artist’s quasi–photo album of images scavenged from flea markets. In it she arranges the varied snapshots in a decidedly non-narrative fashion. Straight-on portraits are followed by aerial shots of apartment courtyards; a color photo of a group contrasts with a faded row of shotguns; close-ups followed by landscapes; overexposed then underexposed.

Tacita Dean. Image from Floh, 2001.

Tacita Dean. Image from Floh, 2001.

Tacita Dean. Image from Floh, 2001.

What stays with us is not merely the images but the trail connecting them. A does not lead to B, though their proximity causes us to wonder how it might. We are left with an itchy sense of the unknown, unable to decipher the contours of the space between the images and wondering what has been left out. An alcohol-soaked night is like this: cause does not lead to effect, the past does not predict the future, and the path from here to there is covered in fog.

Though they may not cohere, the brief flashes of recollection from a drunken escapade can be particularly bright. I remember the startled look on the hostess’s face as I retrieved my purse, the hazy street lights along the Embarcadero, and the way the double doors gave as I pushed my way between train cars looking for a seat. In these memories’ brilliance and disconnectedness, I’m reminded of Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1977–ongoing), her evolving slideshow of photographs taken over a thirty-year period. The images do not connect in a logical sense; most stand alone as shimmering documents of nighttime adventures. Drugs and alcohol are suggested in many of them, and this implicit sense of intoxication explains and allows for their collective disjointedness. Goldin tells the story of revelry and its aftermath. She shows us the bright costumes and black eyeliner of the evening, and she shows us the next day, too: the crease of sunlight that interrupts a darkened room, the bruises, the needle marks. The color-saturated images are so vivid they nearly burn.

Nan Goldin. Couple in Bed, Chicago, from the series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 1977. Dye destruction print. Courtesy of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Nan Goldin. Jimmy Paulette & Misty in a Taxi, NYC, 1991. Dye destruction print. Courtesy of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

A few days after the party the Human Resources department posted photos on the intranet. I clicked “slideshow” and watched the night unfurl: posed scenes gave way to blurry crowd shots, timid smiles became drunken toothy grins. I looked for myself, hoping a photograph could explain everything I had forgotten. No such image appeared, an absence I both appreciated and felt disappointment in. How would a photograph function in this context? A drunken blackout challenges the photograph’s status as document. If we can’t remember doing it, can a photograph contradict our denial? Often said to be a substitute for experience, can a photograph stand in for an experience we did have but don’t recall?