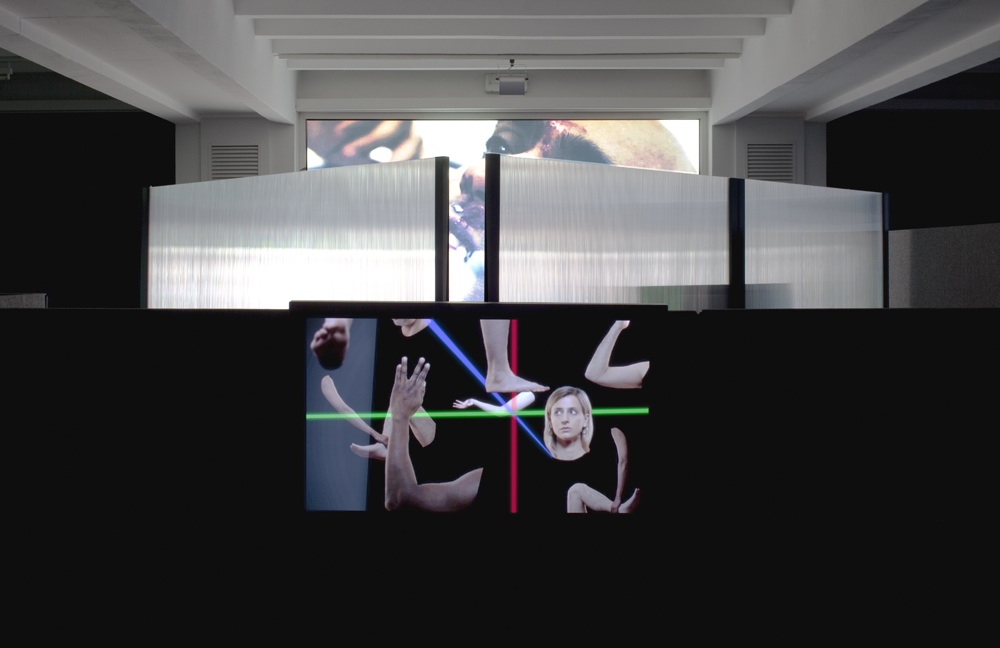

Melanie Gilligan. "Popular Unrest" (2010). HD video, five episodes, total running length 67 min.

Encountering Melanie Gilligan’s work only four years after the financial collapse of 2008, there is a uncanny sense of recognition: that she is providing an extemporaneous fiction for our time. Worlds nearly like our own, but set just beyond it, exaggerating its features. That she is also looking forward to a future time, a world that we might wish for in our present.

One quality that lends the work this sense are her uses of language. In both Popular Unrest, Crisis in the Credit System, and Self-Capital one feels the language is thoroughly of a discourse about financial capital. Gilligan understands this language so well that she can play with it, revealing its shibboleths and operative myths. One could start to talk about these uses of language in Gilligan’s Crisis in the Credit System, in which she shows financial analysts in workshop/group therapy improvising ways to cope with a volatile marketplace. Or in Popular Unrest, which imagines a social universe where market exchange has been perfected by a force called the “World Spirit.”

All of Gilligan’s work investigates the feeling of (political) economy. Which is to say, what the affective cultures and structures of feeling are that undergird economic relations in advanced Neoliberal societies. Crisis in the Credit System offers both a cynical view, in which traders/analysts know what they do all too well, and yet keep doing it (that is until the end of the miniseries when they become the victims of the very system they have been instrumental in creating). In Self-Capital, a video series from 2009, the individual is figured through its doubling in affective and im/material exchange. This doubling is envisioned through an actor who plays both analyst and analysand, among other roles that reverse the polarities of self and other.

The most radical kernel of Gilligan’s exploration of economy and affect may be found in Popular Unrest. While the World Spirit randomly murders citizens, stabbing them from above with a dagger—a situation that literalizes the brutal logic of the current world financial market—it also draws groups of strangers together inexplicably. On the one hand, these groups seem indicative of relationships facilitated by social media and Internet analytics, through which forms of intimacy and senses of community have obviously become thoroughly mediated. On the other hand, they also resemble the affinity groups and resilient swarms driving global occupations and revolutionary movements. Gilligan’s art reveals these intersubjective phenomena to be not exclusive but rather inextricable in our current political climate.

1. What is your background as an artist and how does this background inform and motivate your practice?

I left Canada after high school to do an art BA in London. During my degree I began to feel dissatisfied with the type of life this was training me for: a professionalized career fit-to-order for art institutions and the art market. So after college, I went into other things. I co-edited a book on art, work and immaterial labour and wrote articles and essays on politics, science, economics and art. At the same time I worked quasi-professionally as a scriptwriter, an occupation that fed a dream I had of filmmaking.

When I returned to making art, my work was very influenced by my activity writing scripts and theoretical texts. My first performance, The Miner’s Object, consisted of a monologue I wrote, which was performed by an actress using public speaking teleprompters. The work told a series of stories within stories that conveyed different positions in a theoretical argument through characters and events. My two subsequent performance works involved a similar structure.

2. Do you feel there is a need for the work that you are doing given the larger field of visual art and the ways that aesthetic practices may be able to shape public space, civic responsibility, and political action? Why or why not?

Need… that’s an interesting way of putting it. I think that when I started making my drama about the financial crisis, Crisis in the Credit System, I started to try to address what I thought was truly needed in the world. I made a work that was inserted into mass culture (without aping its forms or content) because I thought that the film was needed in that context, at that moment. Crisis… is a fictional drama that looked at the (then developing) financial crisis of 2007-onward when the world was still mostly in the dark on the subject (I started making the piece in 2007, it came out two weeks after Lehman Brothers collapsed). I began making the film with the idea that people needed to know about the financial crisis as the event would have a profound impact on all aspects of our increasingly financialized world. But I wanted to use narrative, not documentary, to tell people about the crisis, and communicate the information by a different means. I wanted to get the work beyond art spheres to a wider mainstream audience and I realized that distribution would be key in this. I decided to show the work online, dividing the video into episodes so that it fit the size limits of online sharing sites back then. The episodic format led me to model the work around TV drama. I tried to insert information about the work in newspapers and news websites, which are the conventional means by which one learns about an event like the financial crisis.

As I continued to work in a similar vein in 2009, I looked at what would happen after the financial crisis and imagined that we would see intense austerity measures in which the conjoined forces of capital and state would cut back on the social spending that would normally reproduce people’s labor power through health care, education, welfare, etc. This would bring intense frustration, anxiety, pain and confusion (in other words, what we see today), not to mention hardship, hunger and death (e.g. suicides in Greece). So in 2009 – 2010 I made two more films, Self-Capital and Popular Unrest that dealt explicitly with this. Both films explore these affective and bodily impacts while, in Popular Unrest, the focus is capital’s new configurations of biopolitical control–for instance, the increasing importance of algorithmic data analysis in predicting people’s behavior. In the film, it is precisely these sorts of affective states that capital seeks to understand.

I make these video works to be watched online as much as in galleries or screenings. I guess I see my work as something for an imagined future moment, after the film and TV industries crumble and new hybrid forms of D.I.Y. video making, viewing, and thinking about what we watch have evolved. I would be happy for divisions between film, TV, and artists’ films and video to collapse along with the distinction between edifying information (e.g. news or documentary) and entertainment.

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired your work? Please describe.

Lots of things inspire me in my work but they generally aren’t art. That is, in the strict sense of visual fine art. Maybe I shouldn’t say that, but it’s true. When I was making The Miner’s Object I was anti-influenced by, or compelled to argue against, the increasingly dominant paradigm (or excuse for barbarism) that cognitive science and neuroscience provide in contemporary western culture. When I made Prairial, Year 215 it was Denis Diderot and the French Revolution; with Prison for Objects it was a mixture of Marx’s economic analysis, Panofsky, Medieval memory theaters and some excellent thinking by my friend Daniel Berchenko.

During the making of Crisis in the Credit System most of my inspiration came from the financial system and its crisis, though I was also inspired by The Wire, which took an ambitious new direction in television. The brevity and brilliance of [R. Kelly’s] Trapped in the Closet really stuck with me too. Also around this time I discovered the post-revolutionary Soviet theatre troupe Blue Blouse who called their plays “the living newspaper,” which was partly what I had been trying to do here and in my performances. With Popular Unrest I was visually inspired by David Cronenberg and was intrigued by contemporary American forensic crime TV shows (CSI, Bones, etc) as social symptoms of capital-state’s increasingly attention to the body (i.e. caring for it and rethinking it in monetary terms). Across all my works, my biggest influence is my political commitment to changing the economic and political system we live in and striving toward another, better one.

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

Ah, memories. I’m not sure if I’d ever call working on art massively enjoyable, but I wouldn’t call it un-enjoyable either. It’s work and it’s often physically hard to extract that work from oneself. If we are judging this on pleasurable feelings, I would say that I really like the feeling of directing films. Crisis in the Credit System was my first time directing so that was very exciting, in a frenetic, adrenaline fuelled way. I also really liked making Popular Unrest because this gave me the chance to direct and form the film in a more generous manner, with what was for me a large cast and crew. Popular Unrest also really satisfied my intense love of writing scripts as a mode of formal exploration. Again, I say love, not enjoyment or ease.

What I also “enjoyed” last summer was making a series of performances at Cage (a space in New York’s Lower East Side) where I presented performances every Tuesday and Thursday morning at 10:30am. This ran for around a month. I performed in the works myself, testing and molding the social dynamics between the audience and myself. I was trying out a set of ideas regarding the place given to emotion and feeling in art and in culture at large through chaotic, uncomfortable confrontations. It was exhausting making up a new performance every few days but at the time it seemed like it had to be done.

5. What projects would you like to work on in the future? What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

I’ll answer the first part of the question first. Right now I’m working on a project that is inherently confusing. I’m making another video series, which is about a global revolution taking place. In the Marxist /communist tradition it is understood that for revolution to be effective it has to be global but there’s never been a global revolution. There’s another component to the story, which is what’s confusing me. The revolution is happening at the same time, and is probably being caused by a new technology that allows people to feel each others’ feelings, affects, emotions. The subjective boundary of what’s individual and personal breaks down. The difference between the individual and collective bursts open. It isn’t simply that now that we can feel each other’s feelings everything is ok. The technology creates all sorts of difficulties and contradictions. In fact, I’ve realized that it poses incredible puzzles for me in terms of the acting and directing. When I made Popular Unrest I suppose I opened up a Pandora’s Box by experimenting in creating non-individual subjects – i.e. I developed that film using acting workshops in which I asked the group of actors to work together to make up different aspects of a particular person or of an emotional state. I was trying to push for a breakdown of individual, separate characters and to see if I could depart from making the type of drama that is premised on this separation. I didn’t get all the way there by any means but I think I made some headway. But now with this new film the questions that arise from the premise are potentially more difficult to handle – e.g. what would feeling someone else’s feelings mean, and how do I as a filmmaker represent it? These questions are challenging but fascinating because thinking them through has implications beyond the construction of the film to broader inquiry pertaining to political solidarity and collectivity.

To answer the second part of your question, the direction that I imagine taking after this is that I want to expand my work into creating actual systems that directly affect the culture and society that we live in, both in the art world and without.

Pingback: Melanie Gilligan. Crisis in the Credit System. « Re-