Through her projects, Zoe Beloff historicizes technological potential, and especially the potential of post-cinematic media to tell history fresh. Taking up Walter Benjamin’s preoccupation with technologies of mechanical reproduction, she correlates the use of these technologies with modern mediumship. Like those spiritualists who participated in the most prominent political struggles of the late 19th and early 20th centuries (abolition, women’s suffrage) speaking through the dead provides an effective mouthpiece for opposition. Psychoanalysis and spiritualism become conflated in Beloff’s work, inasmuch as both discourses view the subject through unconscious processes and unacknowledged archives. This comes across especially in Beloff’s project for the Coney Island Psychoanalytic Society, which celebrates minorities who chose to practice psychoanalysis collectively in the working class neighborhood of Brooklyn.

The spirits have sprung to life in Beloff’s most recent work, which takes up Brecht’s learning play, “Days of the Commune,” within the context of the occupations. In the spirit of Brecht, Beloff does not seek to reenact the Paris Commune, but instead articulates two historical moments through one another, proving the events of 1871 and 2011/12 contemporary. The cast of Beloff’s version of the play, set at Zuccotti Park, consists largely of strangers, many of whom are professional actors and activists enthusiastic to collaborate in their off-hours.

1. What is your background as an artist and how does this background inform and motivate your practice?

I grew up in Edinburgh Scotland. I had a very conservative education. The curriculum in the Art College had not changed since the nineteenth century. We were trained to make tasteful canvases to grace the walls of the Scottish bourgeoisie. So of course I rebelled. I felt at the time that if the school taught me anything it was not to rely on praise or encouragement of the professors. I learned to study on my own.

As a teenager, I fell in love with cinema and on graduating I decided to go to film school. By something that I can only think of as a terrible mistake on their part, I was accepted into the graduate film department at Columbia University. Most of my classmates wanted to make Hollywood comedies. Once again I felt like a fish out of water. It wasn’t till the mid-1990’s that I began to discover what I wanted to do. I came to the realization that my work was to create conduits between past and future, reanimating history so it can speak again in a new way.

The strange thing is that thirty years later, I find that I am putting into practice many skills that I learned in my academic education but in a way that is my own. I have only begun to exhibit drawings in the last few years but now it is a very important part of my practice. I’m even studying the drawings of nineteenth century artists like Courbet and Daumier, learning from them and engaging with their work politically. And of course when I went to Columbia, I studied with some amazing people: Stefan Sharff, who had worked with Eisenstein and had this fascinating formalist perspective on film, and Sylvère Lotringer, who introduced me to radical French philosophers. My work has always been both very hands-on and at the same time theoretically-oriented.

2. Do you feel there is a need for the work that you are doing given the larger field of visual art and the ways that aesthetic practices may be able to shape public space, civic responsibility, and political action? Why or why not?

Is there a need? An odd word, is my art useful, do people want it? I don’t know. But I do believe that I have something to say that needs to be said now.

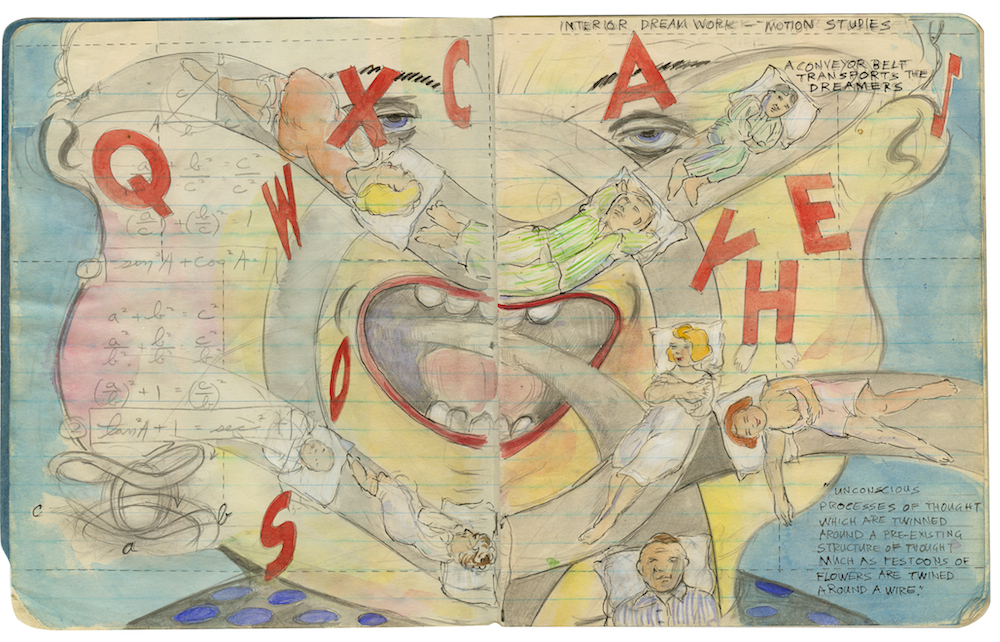

In the last few years my work has focused on utopian communities, ordinary people who decide to change their world. My exhibition, “Dreamland: The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and its Circle 1926-1972” is about a group of working people who came together to explore the intimate politics of desire. Though the Society is, so to speak, an “urban myth,” I see the project not only documenting the social history of a particular place but as a potential, an inspiration for a society that could come into being.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1sD1H1vwn0U]

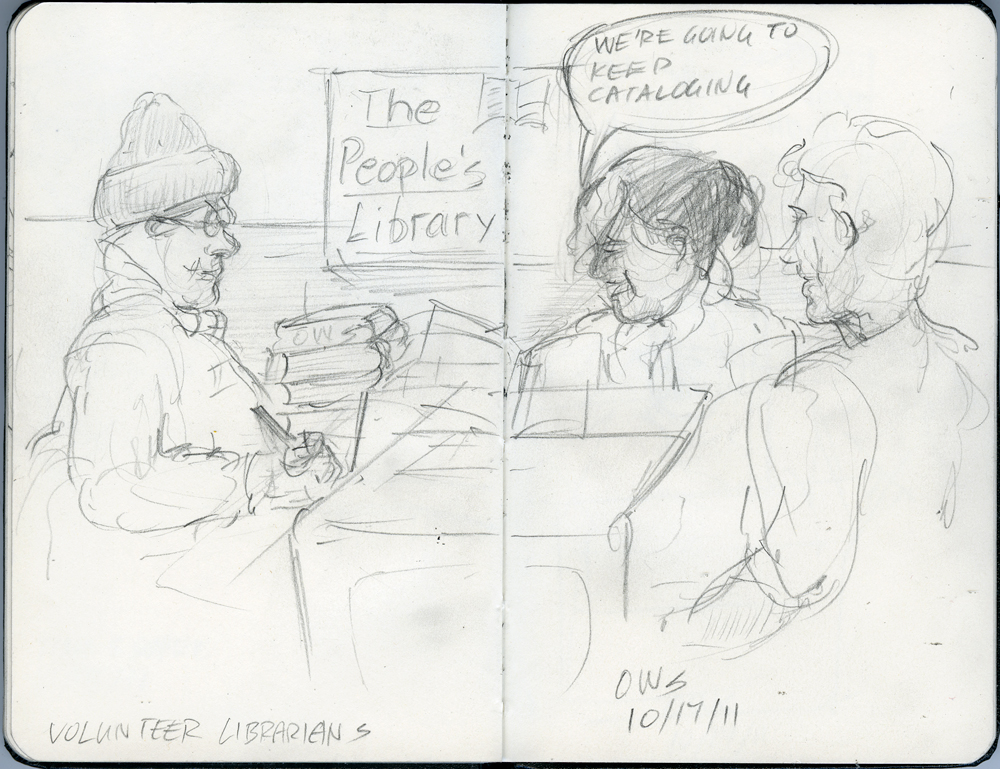

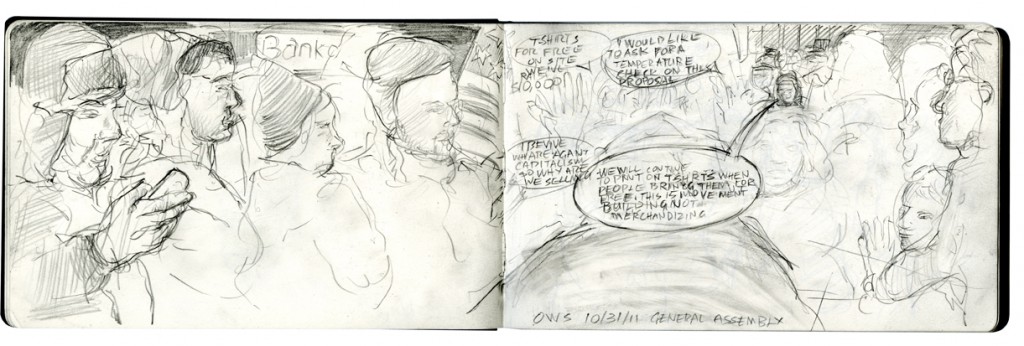

When Occupy Wall Street appeared, I realized that here was a real utopian society, not far from my apartment. I didn’t camp out, but I was inspired to respond right away, doing things I’d never done before as an artist. I’d be at these General Assembly meetings, drawing in almost total darkness, making a kind of documentary comic book. I started to think back to Courbet and Manet documenting the end of the Paris Commune. Though it might only be one city block wide, OWS was a radical theater of the people. I wanted to do more than just document. I wanted to contribute something. As it happened, I was reading a biography of Brecht and discovered he wrote a play called “Days of the Commune.” I knew what I must do. I had to put on the play right away. That is something that Occupy really reaffirmed for me, that one must act now without waiting for funding or permissions.

The Paris Commune of 1871 was the first great modern Occupation where working people took over their city and formed a truly progressive democracy. Many different left groups came together and women played an important part defining and demanding feminist principles. They had so many great ideas that are relevant to today. They decreed that education should be free, that no house should stand vacant while workers were homeless. Brecht shows us everyday life during the Commune and at the same time asks us to think about how political and economic forces shape lived experience. The play invites us to imagine what would happen if a new kind of people’s democracy took over a city today. How could it survive against the forces of Global Capital? How should it respond to armed attack? These questions are relevant today both to the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement. He doesn’t provide answers. Instead he invites each of us to think for ourselves.

[vimeo:https://vimeo.com/43256575]

How was I to put on this play with a cast of fifty speaking parts? I didn’t have access to a theater. The answer was obvious–perform at Zuccotti Park and other public spaces around the city. I decided to bring together a band of performers, not only professional actors but everyone who had a desire to participate. We all have day jobs so we would work on weekends. The project was not simply about creating a spectacle, but would take the form of work over time. Like building any kind of movement it would incorporate the process of learning. I would make all the props and scenery out of corrugated cardboard because cardboard is the medium of protest. We would not get permits. We would just do it. And we did. Our performances lasted from March through May. In this way we layered our contemporary project over the three months that the Paris Commune existed before it was destroyed by the French army. We handed out broadsheets to spectators. We documented the performances and posted them online.

And if politics begins with oneself and those who we work with, I could say we learned a lot. This project changed the way I work. It isn’t polished in the conventional sense. It starts off in confusion. But amazingly, just as I had hoped, it grew. Performers joined in along the way. The last performances are a far cry from the first ones.

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired your work? Please describe.

My terrain is the detritus of history. Objects that are considered worthless and obsolete are often the most important to me. The flea market is an endless source of lives momentarily reanimated through snap shots, scribbled notebooks and home movies. I’ve always thought of home movies very much the way Freud thought of slips of the tongue or jokes, as revealing far more about our inner lives than people ever suspect. These ideas were behind the “Dream films” I made for the Coney Island installation.

My recent installation, The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff, was inspired by a series of efficiency studies that I rescued from the library at Baruch College when they decided to throw away all their 16mm films. These films showing the industrial process, the manipulation of things and people at its most elemental, became the starting point to explore relationships between capitalism and the cinematic apparatus.

Of course I look at all kinds of art. I have learned an incredible amount from the Wooster Group since I first saw their work in the 1980s. Recently I have been thinking about the work of filmmakers Jean Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, particularly their film History Lessons which was in some ways a model for The Days of the Commune.

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

My favorite projects are those that are the most expansive, in which I create worlds, worlds that I live in imaginatively for long periods of time. Beyond was the first. It began as a serial film on the web in 1995, made with a tiny black and white webcam, that grew into an interactive work; it was an exploration of the relationships between the imagination, the unconscious and the birth of mechanical media between the 1850s and 1940. In the 1990s I felt that as we entered the digital age it was important to talk about how technology was deeply linked with psychological and philosophical ideas.

The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society is an archive, and like any archive, potentially endless. It was more than just an exhibition. Even after the show opened at the Coney Island Museum I was not done with it. I am still working on it. Even though the members of the society are fictional, I still feel responsible as the spokesperson for ideas that they embody. The founder, Albert Grass, is an homage to the Jews of my grandparents’ generation, working people who believed in social justice and the idea that on a personal level it was possible to change the world. I tell people who ask about him that he and I “are as one.”

This brings me to my third favorite project, The Days of the Commune. This time I’m not working with a fictional society but an amazing group of real people. I had hoped these contemporary Communards might be as diverse as New York City itself and that turned out to be very much the case. They all inspired me, and I want to complete a work they can be proud of.

Right now I’m turning the project into an installation, a space one can walk into and reflect upon, that includes a film plus the props, banners and drawings that suggest a protest waiting to begin. Again, I plan to work to contextualize both the Paris Commune and issues raised by the play within our current social landscape.

5. What projects would you like to work on in the future? What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

I don’t know. I want to be sensitive to what is happening in the world around me. I don’t think I’m done with Brecht yet. Recently I was invited to be part of a show to celebrate the centenary of the birth of the great cineaste and founder of the Cinémathèque Française, Henri Langlois, in 2014. Who knows where that will lead me.