Pablo Picasso. “Study for Sculpture of a Head (Marie-Thérèse) (Étude pour sculpture d’une tête [Marie-Thérèse]),” summer 1932. Charcoal on canvas. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel. © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Peter Schibli, Basel.

Picasso Black and White is on through January 23, 2013, at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. On the rainy Sunday after it opened, it was a mobbed, tourist-heavy scene of lines and irritation. The question arises, and certainly arose for me, whether there is anything left to say about an artist so iconic, a name synonymous enough with “artist” as to be a cliché. Also, whether any oeuvre, no matter how definitive or diverse, can support all that adulation and scholarly attention and curatorial reconfiguring and still have anything new to say about itself. The Guggenheim, finding an unoccupied space in the crowded history of Picasso exhibitions, is the first to mount a show exclusively focused on the artist’s work in black and white. I wondered, along with a lot of other people, about the relevancy of this undertaking.

But Black and White is a surprisingly gratifying exhibition—it feels energetic and new, and it repeatedly rewards on the visual level. Stripped of color, the exhibition highlights Picasso’s aggressive experimentation, the relentless investigation into form, the texture and chromatic potential of gray scale, the structural genius in the work. It’s aesthetically fascinating. It also seems to mirror, thematically, the essentialist nature of the artist’s preoccupations, the repeated iconography of sex and death, fear and desire, examined and re-examined throughout a lifetime. I’d argue that this is the rope that keeps pulling people in.

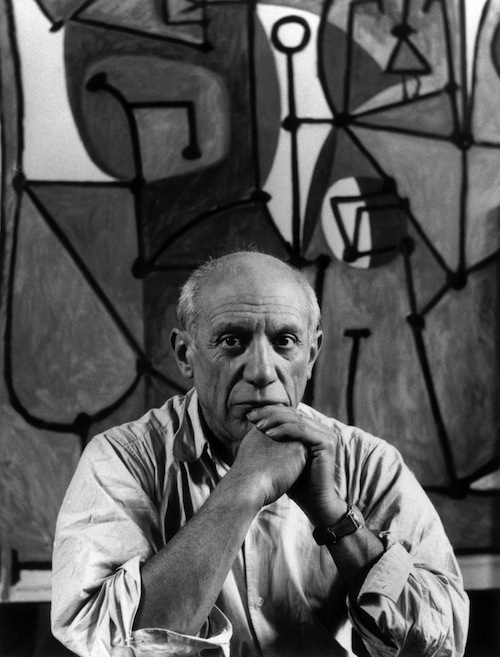

Pablo Picasso in front of “The Kitchen” (“La cuisine,” 1948) in his rue des Grands-Augustins studio. Photo: Herbert List/Magnum Photos.

Biography is big at Picasso shows. Here the Guggenheim’s curvilinear, whirlpool-like space is ideal for the exhibition’s chronological progression—we gradually ascend upwards through Picasso’s life, 1904–1971 (two years short of his death in 1973, at the age of 91).

Maybe it is the exhibition’s chronological structure, but the influence of the lover-muse feels as if it’s everywhere. Not in a good way. It’s disturbing to see Picasso working through a series of formal explorations in his painting by working through a series of women, discarding one for another as his style evolved (almost always on his terms—the only woman to leave him was the artist Françoise Gilot, mother of Claude and Paloma, and the subject of last summer’s joint show with Picasso at Gagosian).

By nearly all accounts, Picasso was a psychologically brutal man to love—he could be charming and adoring, but also emotionally needy, vindictive, jealous, competitive, domineering. The emotional afflictions we all have in varying amounts, he seemed to have in excess. He could be alarmingly cruel. As a sufferer, he had a great capacity to inflict and then justify suffering in the women he loved. For him, as he told Paul Éluard, love affairs involved “a lot of gnashing…two bodies entangled in barbed wire, rubbing against each other, tearing themselves to bits” (Richardson 329). On canvas, this pain cohabitates, comingles with ecstasy, again and again.

Pablo Picasso. “Head of a Woman, Right Profile (Marie-Thérèse) (Tête de femme, profil droit [Marie-Thérèse]),” 1934. Oil and charcoal on canvas. Collection of Aaron I. Fleischman. © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

The lightest work here, in tone and feeling, is from the late twenties, the time of Marie-Thérèse Walter. Picasso was still married to the dancer Olga Khokhlova— Madame Picasso of the large-limbed neoclassical portraits further down the Guggenheim’s ramp—when he met the seventeen-year-old Marie-Thérèse in 1927. He became infatuated with her, particularly her physicality, the athletic swimmer’s body so out of keeping with the Flapper era. She’s often depicted in profile, that familiar strong bridge of nose, or in sweeping, rounded lines—asleep.

Far more evocative, though, is the series of elongated forms done during the same time, in which Marie-Thérèse is often disguised, abstracted, fused with the act of lovemaking. These are figures that seem to capture the languidness of love, the way the body feels transformed, how time seems to stretch, spread out horizontally. Here are idle afternoons on the beach, in cabanas. An exhilarating happiness. All of the intensity and transience of it.

The series ends, in a sense, with a beguiling little work called The Kiss (1930) in which two groping faces amorphously interlock with all the desperate need and vulnerability of panicked lovers. Their open mouths strain towards each other, inside each is a knifing tongue the shape of a dagger. It is the tongue, as Picasso sees it, the soft, unguarded thing behind the barrier of teeth, that which your own desire has made you so vulnerable to, that will do you the most harm.

The dagger tongue is a motif, and we will see it again, emerging from a twisted equine mouth in Head of a Horse, Sketch for Guernica (1937), a study for the monumental Guernica, objecting to the Spanish Civil War. So much of what’s horrific and unnatural about war is in the horses’ twisted expression, the straining throat, and panicked, enlarged nostrils.

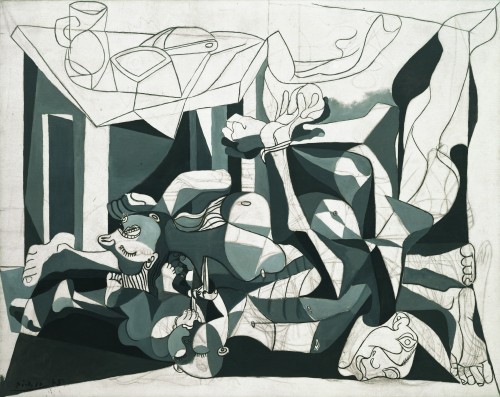

Pablo Picasso. “The Charnel House (Le charnier),” 1944–45. Oil and charcoal on canvas. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mrs. Sam A. Lewisohn Bequest (by exchange), and Mrs. Marya Bernard Fund in memory of her husband Dr. Bernard Bernard, and anonymous funds, 1971. © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

By working from the black-and-white palette, Picasso was following a long tradition of Spanish painters, El Greco, Francisco de Zurbarán, Diego Velázquez, and Franciso de Goya. Several of the works in the show pay direct homage to these masters, including The Maids of Honor (Las Meninas, after Velázquez) (1957) and The Charnel House (1944–45), indebted to Goya’s Ravages of War (1810–12). But unlike in Goya’s etching, where the hellishness of human cruelty pervades every inch of the work, extending outward, in The Charnel House, the boundary between the horrendous and the sublime is repeatedly transgressed, in the curved arcing lines, the geometry of dark and light. It is in these later works where Picasso’s interest in tonalities, his ability to push this monochromatic language to full expressiveness, is most dazzlingly on display.

The exhibition concludes with another painting of a kiss. Here is Picasso’s second wife, Jacqueline Roque, who fell in love with him at twenty-seven (he was seventy), jealously protected him and his reputation, took on all his grudges and resentments and gripes as her own, deferred to and supported him, a martyr to the mythology and to the man, his life’s final lover, multiply represented in the later years with her signature bangs. The dominant read around the painting on the day I was there was that it seemed sweet. This is a more impotent version of the 1930 kiss, the mouths are fleshy-lipped, toothless, they move towards each other with a pressing need. Instead of knifing forward, the tongue drifts like smoke into the mouth of the beloved. The Kiss was painted in 1969. In 1977, four years after Picasso’s death, Marie-Thérèse would hang herself in the garage of her home. Nine years after that, Jacqueline Roque would also commit suicide, unable to ultimately reconcile the life she was living as her own. When it comes to certain types of love, it seems, the danger never really goes away.

Pablo Picasso. “The Kiss (Le baiser),” 1969. Oil on canvas. Private Collection.

© 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: David Heald.

I welcome thoughts, ideas, show announcements. Please email me at [email protected].

Notes

Françoise Gilot with Carlton Lake, Life with Picasso (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

John Richardson, A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917–1932 (New York: Knopf, 2007).