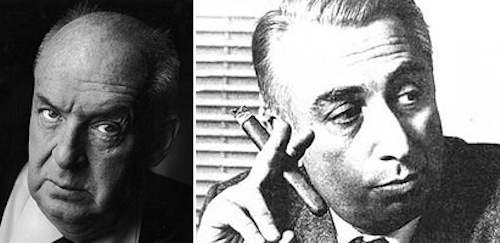

About halfway through my freshman year of college, I abandoned plans to major in English, choosing instead to pursue my newly discovered passion for art history. I have never been able to fully explain the cause of that abrupt decision, or at least not until a few weeks ago, when I read an essay by the British author Zadie Smith. The essay is called “Rereading Barthes and Nabokov,” and in it, Smith recalls her experience studying literature at university. She (fondly) remembers professors who encouraged “wild analogy” and “aggressive reading against the grain and across codes and discourses.” The essay revolves around a comparison of this kind of analysis, favored by Roland Barthes, with the kind favored by Vladimir Nabokov, which is almost diametrically opposed to it. As it turns out, I stopped studying English because I identify more with a stodgy Russian novelist than with a progressive French theorist.

Here is the gist of the comparison: Nabokov believed in the importance of studying style and structure, and the indelible link between the author and his writing; Barthes (who was 15 years younger, but still very much a contemporary) championed the “death of the author,” maintaining that the author’s biography and intention should have no influence on the reader’s interpretation of his writing.

I quit taking English classes because I got tired of professors telling me to read deeper into things when I was convinced I had gotten to the bottom of them. I was sick of being reminded of the phallic symbolism in every story about a man going fishing and of being encouraged to interpret novels written at the beginning of the 20th century as warnings about the evils of consumerism and technology. I just wanted to return to reading whip-smart prose and marveling at intricate plots and beautifully developed characters. I wanted to love reading fiction again, and in order to get that back, I had to give up reading for academic purposes.

What immediately attracted me to art history was that all arguments had to be grounded in visual evidence. Art is just visual language, and there are no fundamental differences between interpreting a painting and interpreting a paragraph; still, visual imagery has always felt more concrete to me than linguistic imagery. I perceived less of a risk in ending up miles away from an artwork’s original meaning, because I could always check my suppositions against what I was looking at.

Work that I had once deemed ugly and unappealing opened up to me as I learned about artistic process and historical context. I took a senior seminar about three artist couples and went from being repulsed by the garish pinks and crude figures in Willem de Kooning’s paintings to poring over images of his work for hours, dazzled by the simultaneously corporeal and emotional struggle that their creation represented.

Art history appealed to me because it honored context and intention. It allowed me to consider why the work was created, and to convert that knowledge into understanding and appreciation of the art. But at some point, I realized that studying art history is not the only way to access a work of art. As I began to spend more time in museums, engaging in conversation with people not versed in the discipline, I finally understood that Nabokov’s approach to interpreting art only works if you already connect to it. But if you don’t connect to it right off the bat, then a different kind of interpretation – a Barthesian one – has the potential to help you do so. Some of my favorite exchanges in museums have happened with elementary students, in front of works of art that I knew they were absolutely wrong about. And yet, they had discovered a way to make sense of the work by relating it to their lives. What could honor the efforts of an artist more than that?

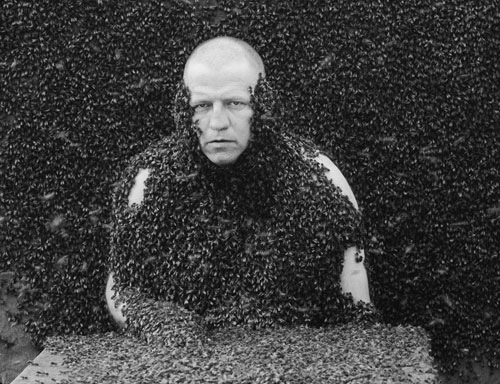

During a visit to the Hirschhorn Museum in early August, I had a chance to watch a short video by the Dutch performance artist Jeroen Eisinga called Springtime. In the 20-ish minute silent film, the artist sits, blinking and immobile, as over 250,000 bees gradually envelop his body. The only adjective I can think of that properly describes the work’s effect on me is transfixing. Watching the film gave me what Zadie Smith poetically identifies as the payoff for reading like Nabokov: the chance “to reconstruct the bliss of… [the] writerly act.” For 20 minutes, I was Eisinga’s disciple; I followed his style and his structure, and I was rewarded with a glimpse into what it must have been like to be in his place.

The thing is, I only enjoyed Springtime because I was prepared to enjoy it. I am very comfortable with contemporary art, somewhat familiar with performance art, and generally untroubled by the blurring of boundaries between and across genres. I understand that shock value is a factor in a lot of performance art, but that it’s often a superficial interpretation of an artist’s motivations. Someone without the same exposure to art would likely have not lasted two minutes in the screening room. And yet I am confident that, given the opportunity to talk about the piece, they would stumble upon opportunities to personally connect to it.

Here is my favorite line in Zadie Smith’s essay, and the crux of her argument: “you can storm the house of a novel like Barthes, rearranging the furniture as you choose, or you can enter on your knees, like the pilgrim Nabokov thought you were, and try to figure out the cunning design of the place – the house will stand either way.” Smith is telling us that we can have it both ways. It doesn’t matter how we interpret – as long as we find meaning, we can’t do any damage to the art.

I’m pretty certain this is a really good lesson, and one that applies as much to life (and, in my case, life after grad school) just as much as it does to works of art. We like to set up dialectics for ourselves: money versus happiness, boredom versus exhaustion, making art versus working 9-5. Maybe we should try more often to have it both ways. Can you imagine the fascinating twists and turns our lives might take if we stopped despairing over our inability to balance our passions and our needs, and instead dedicated that energy to finding creative ways of doing just that?