Two exhibitions in Culver City right now do exactly what Showtime’s Homeland should have done.

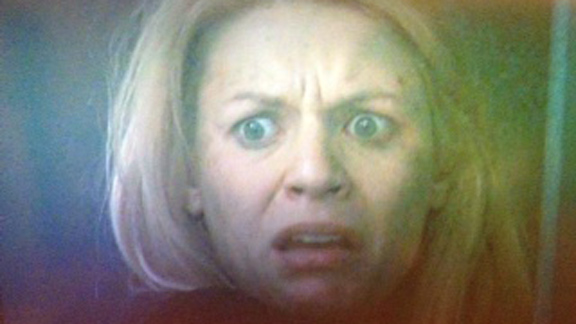

Carrie Matheson, the scorned-then-redeemed CIA agent Claire Danes plays with such nervy brilliance on Homeland, did not have a single breakdown in episode 7 of season 2. In episode 6, she pushed her way into the congressional office of Lieutenant Nicolas Brody, the ex-POW-turned-double-agent she’s handling after he landed her in a mental institution last season. Then she wept. In episode 4, she blew everyone’s cover by telling Brody, in a moment of rash self-doubt, the CIA knew he was a mole. By episode 8, she would be back to bursting into other people’s rooms, and would cut off the tracking device on a fear-addled Brody and take him away to a rural hotel room for reasons she kept from her superiors. When the CIA finally found her again she was “making sex noises” with Brody. Her always-hopeful mentor Saul said, “She’s turning it around,” meaning she’s bringing Brody back into the fold, but the other guy in charge, Quinn, shot back, “Is that someone turning something around or is that a stage 5 delusional getting laid?”

The point is, in an episode like 7, where the most dramatic moments involve Carrie’s chin — the defiantly dimpled chin New Yorker critic Emily Nussbaum calls “crumpled” and says she could write a thesis about — quivering and not her credibility slipping, is a relief.

When Homeland first aired a year ago, Claire Danes’ Carrie seemed like a special boon, even in the midst of the already-rich cable renaissance. There haven’t been that many “serious” female spies on television, spies without plastic perfectness of, say, CW’s Nikita, with no unconvincing personal vendetta and no Mata Hari-style glamour. Behind Carrie’s penetrating, worried eyes, it’s like she had the smarts and tortured soul of John Nash wrestling around with wits as quick as Jason Bourne’s. She’s a hot mess but a dimensional one, not a type.

So when Season 1 ended with a scene reminiscent of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar – Carrie lying back with wires twisting out from the buttons attached to her temples, about to undergo shock treatment – and the hysterical-woman trope reared up in a vicious way, the effect was beyond disappointing. It was chilling.

The chill came mainly from the show’s lack of self-awareness. Remember in The Wire, when McNulty would make pussy jokes in front of Kima Greggs because she’s a lesbian and would, he thought, clearly understand? Or in The Sopranos when Ariana is dismissed by FBI investigators she sacrificed everything for, then killed by the gangsters she loved? In both cases, you understand as a viewer that these are strong women caged in by misperceptions and circumstances. But with Carrie, it’s never quite like that. It often seems the people writing the show have forgotten for a moment that she’s brilliant, even though they created her to be, and started believing she is entirely delusional.

Season 2 just ended with a terrorist attack at a funeral that kills too many innocents and the CIA division chief. But the whole time, you were afraid for Carrie – not because of what might happen to her within the plot of the show, but because you weren’t sure how and when the writing would corner her. It was like seeing progressiveness and regressiveness try to coexist: the brilliant 21st century operative starring in a prime time show but constantly being pulled back into that old model of the female hysteric.

It’s something you see in visual art a lot — progression and regression coexisting, and brilliance of one kind or another being caged by some often-oppressive structure. In L.A. artist Kathryn Andrews’ new exhibition at David Kordansky gallery, the stand-ins are made of stainless steel. Titled D.O.A./D.O.B. (dead on arrival / date of birth), it consists of a steel bed like the kind you’d imagine seeing in a mental or military hospital and a few windows with steel blinds hung on the wall. You can’t see into them, because no openings have been cut behind them. Then there are two tubes 6 or so feet tall standing in the room. One tube has a pile of plastic fruit above it, the kind the Chiquita Banana lady might wear on her head. During the opening, I have been told, a performer stood inside that tube nude, though no one there could see her — a caged vulnerability that you couldn’t really do anything about but were constantly aware of.

A few blocks away at Ghebaly Gallery, Andra Ursuta’s installation, Mothers, Let Your Daughters Out Into the Street, is cool and carefully structured. You see two angled towers of cinderblocks and a red pole stretched between, holding up four colored, smartly rectangular swings that look like things you’d buy at a mid-century modern novelty store. But these swings have a special function. The holes in their seats are shit holes, literally meant for relieving oneself while swinging. They were designed, according to the press release, partly in response to psychologist Alice Miller’s writing about a child hyper-conscious of his parents wishes for him and determined to control everything about himself down to his bowel movements. Ursuta calls the swing set “Natural Born Artist,” and the idea of excrement flying out of those carefully cut holes feels subversive and unnerving even if you’ll never actually see it happen.

That’s what I wanted for Carrie Matheson — a frame like that swing set or the stainless steel tube that limited what she could do or how she could do it while exposing those limitations for what they were.