Khaled Jarrar. “State of Palestine Stamp,” 2011-2012. The West Bank artist stamped passports during the exhibition “Middle East Europe.” Image via electronicintifada.net

This month, I had the pleasure of visiting Czech curator Zuzana Štefková. Now researching at Rutgers University on a Fulbright fellowship, Štefková is known for her challenging curatorial projects that work across religious, ethnic, and social divides. In the following interview we discuss her research in New York and most recent projects.

Marissa Perel: What is the biggest project you have worked on in the past year?

Zuzana Štefková: Middle East Europe, which opened and toured over the course of one year from 2011-2012. It opened in Israel and then toured to the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary, and then Palestine. The idea was sparked by my frequent collaborator, the artist, filmmaker, and curator Tamara Moyzes. We wanted to bring Central and Eastern European artists together with Israeli and Palestinian artists to start a cross-cultural dialogue about conflict in the Middle East. We wanted to implicate Central Europe as part of the conflict, and not treat Middle Eastern artists as the exotic Other. Central Europe is historically part of the problem because of its involvement in the Holocaust. Also, the Czech Republic is one of the nine countries that recently voted against Palestinian statehood in the UN.

A hybrid Muslim-European flag by the Bosnian artist Damir Nikšić, included in the exhibition “Middle East Europe.”

Some Palestinian artists refused to participate in the exhibition because of the presences of Israeli artists. But some did participate, and even come to Prague, where the largest [Middle East Europe] exhibition took place at DOX Center of Contemporary Art. Khaled Jarrar came from the occupied West Bank city of Jenin with his project Live and Work in Palestine. He stamps people’s passports with a “State of Palestine” seal. It’s a symbolic challenge to Israeli’s denial of Palestinians’ right to self-determination. Some Central and Eastern European artists responded to the conflicts by reflecting on religious and racial tensions in their own countries. Bosnian artist, Damir Nikšić, for instance, created a Muslim-European flag. We had it fabricated in Ramallah, and it had to cross checkpoints from Ramallah to Israel and across Europe for the show.

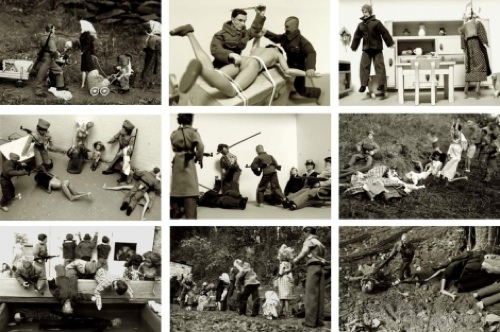

Images from “The Art of Killing,” an exhibition of photographs by the Czech artist Lukáš Houdek. Artwall Gallery, 2012. Image via artesegundodechomon.blogspot.com

An ongoing curatorial project I have been involved in is Artwall Gallery, a public gallery in downtown Prague. It consists of eight stone frames within a wall that flanks the Vlatava River, and is visible from the street. The frames were designed to contain socialist propaganda from the 1950s, and are situated under Letna Hill, where a large monument to Stalin was erected in the 1950s. It was reappropriated in the 1990s as a site for exhibiting socially challenging visual work. It was shut down in 2008 because of its controversial shows, but reopened in 2011. The current exhibition here is The Art of Killing by Czech photographer Lukáš Houdek. He used action figures and Barbie dolls to reenact the scenes of violence that accompanied the forced deportations of Germans living in Czechoslovakia after World War II. The property of these people was seized by the Czechs and it was never questioned by the authorities. Houdek was raised on such a property. Czechs have kept silent about this dark part of our history and bringing it to light causes enormous controversy. Houdek received death threats for mounting these photographs, letters that said, “I hope you die a horrible death.”

MP: Why?

ZS: Because of shame. Because Czechs are afraid that one day these Germans will want their property back. It is a real skeleton in the closet of Czech history.

MP: But at the same time there is a resurgence of Neo-Nazism.

ZS: In 2011, in Northern Bohemia, neo-Nazis organized marches against the Roma population. Unfortunately, citizens see the neo-Nazis as protecting them. There has been a backlash of right wing conservatism against marginalized populations. One of the anti-Semitic and anti-homosexual initiatives in the Czech Republic is the D.O.S.T. movement, with direct connection to president Václav Klaus. In 2011, when Tamara and I were mounting the first exhibition of Middle East Europe at Mamuta Gallery in Jerusalem, Tamara came up with a protest action against then adviser to the Minister of Education and the chairman of D.O.S.T., Ladislav Bátora.

MP: So you were mounting an exhibition and decided to take a protest break? Where did this happen?

Protest against Ladislav Bátora on the steps of Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, September 15, 2011. (Stefokova and Moyzes pictured far right.) Courtesy Zuzana Stefkova.

ZS: It was at Yad Vashem, Israel’s official Holocaust museum. We found out that the Czech Republic’s Prime Minister was visiting with the Minister of Education, Dobeš. Originally, Bátora was also on the team, but he did not join the delegation. We came with two other women to the museum with slogans calling on the Minister of Education to fire Bátora immediately. The signs showed names of cities where the marches against Roma were happening in the Czech Republic, and our names and the year, as if we could be potential victims of these clashes. We were ignored by the officials, but we got onto the Czech evening news. Eventually, Bátora was fired from the position. Later he reacted, saying that the “Jews” conspired against him. This was one action carried out by our feminist-activist collective, Fifth Column.

MP: What else have you done with Fifth Column?

ZS: We participated in Prague’s Gay Pride March, wearing masks of then president Klaus, Bátora, and another ultra-conservative politician, the president’s vice chancellor Petr Hájek, who were all against the march. We wore masks of their faces, leather and strap-ons on our bodies, mocking the politicians in our S&M performance-protest.

Štefková shouts into a megaphone while wearing the mask of former Czech president Vaclav Klaus. Moyzes stands behind her wearing the mask of former adviser Petr Hajek. Image via The Atlantic

MP: How does feminism connect to your political curatorial work and your activism? Is protesting and street performance part of the same world for you as curating?

ZS: I tend to distinguish between these areas of my life because they require different perspectives. As a curator, I try to keep a balanced perspective on the work I am exhibiting and its cultural messages. But in creating performance-protests, I am openly acknowledging my activist position. I consider myself a feminist, although this year will be the first time I’ll be curating an event that is explicitly feminist.

MP: What is the show?

ZS: It’s going to be called Frida Workshop [and installed] at DOX Center for Contemporary Art, Prague in May. It’s co-curated with Slovak artist Petronela Tančeková. We’ll present three beds with three artists inhabiting them for five days. Each of the artists will work with her identity and challenge essentialist views of femininity.

MP: And feminism is connected to your Fulbright research here in New York?

ZS: I’m researching the connection between feminism, art history, and pedagogy. Within the policies of art academies, the inheritance of the dominant male perspective on art is undeniable. Finding a way to change that perspective is still challenging. I’ve been interviewing women artists who are or were active in academia as art professors. Mira Schor, Martha Rosler, Faith Wilding, and Joan Semmel—I plan to interview many more. I want to learn for myself how to apply feminist pedagogy and research—how have feminist artists moved from the position of outsider to the position of authority?