Emily Mast. “Birdbrain (Addendum),” 2012. Video still. Courtesy the artist and LACE.

It’s been something of a French spring in Los Angeles, as the Ceci N’est Pas… initiative, organized by the French Embassy, has brought numerous Gallic artists and curators to town for residencies, group exhibitions, and other fun projects. Some of the projects have had intensely LA-centric themes, such as the high-profile group exhibition LOST (in LA), which used the television show “Lost” as a loose framework within which to explore creative linkages between LA and France. Such projects have presented intriguing opportunities to look at our city’s histories, cultures, and mythologies through the refracting lens of a foreigner’s gaze.

Perhaps the most endearing and welcome of these LA-focused exhibitions was LA Existancial, an examination of the legacy of influential French-born artist Guy de Cointet, who lived in LA from 1968 until his death in 1983. A local cult favorite for many years, de Cointet has only recently received wider recognition from the art world at large. Along with contemporaries like Al Ruppersberg and William Leavitt, he played a significant role in the development of California Conceptual art. Interestingly, his status as a foreigner who came here without a firm grasp of the English language played a crucial role in his practice; he came to see language not so much as a tool for conveying meaning as an archive of aesthetic objects to be examined and manipulated. His two-dimensional works made heavy use of abstract arrangements of text, influenced by Surrealist and Dada art, semiotic theory, and WWII-era encoding methods. He was also fond of staging theatrical productions, utilizing the conventions of theater to deconstruct the clichés of visual and verbal communication.

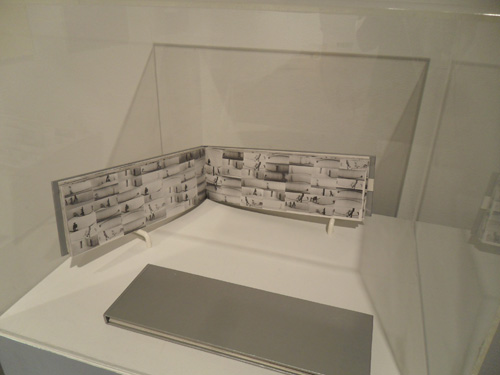

Sophie Bonnet-Pourpet. “Dear Aaron, The Wallpaper Has Some Existancial Problems,” 2013 (left) shown with five serigraphs by Guy de Cointet, 1973. Photo: Josh White.

Curated by Marie de Brugerolle, the leading scholar on de Cointet’s work, and presented at LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions), LA Existancial included a small grouping of de Cointet’s prints (as well as an opening night performance of a few of his stage pieces) alongside a range of works by artists hailing from LA, France and around the world. All of these works showed an overt de Cointet influence, whether consciously employed or not. Playful, provocative, and smartly curated, the exhibition did a great job of opening up the often inscrutable French artist’s work to a broader and livelier realm of engagement.

The show started off on the right foot with For Godard (2013), a new collage work by the godfather of California Conceptual art, John Baldessari. Against a grid paper background, a series of wooden rulers attached end-to-end unfold like a fence. On each ruler is written a period in art history, like Baroque or High Middle Ages. Over this whole pattern are written the words: “In L.A. artists don’t worry if their work doesn’t fit into art history – they say “who cares” / Art history can be like a film with jump cuts.” The work seems to reference the way this city’s extensive network of art schools fuels and shapes its community while at the same time, the city’s culture gives artists the freedom to improvise. Although dedicated to Godard, another Frenchman with a relationship to LA, it could easily have been about de Cointet, who initially came to the city as Larry Bell’s assistant.

Guy de Cointet and Larry Bell. “Animated Discourse,” 1975. Photo: Carol Cheh.

I first saw Emily Mast’s Birdbrain (2012) performed in a theater setting last year—first in a test version at Liz Glynn’s Black Box performance speakeasy, and later in a more polished version at REDCAT. The work is kind of an Olympic exercise in semiotics, exploring the boundary between mimicry and meaning in a series of colorful skits performed by an eclectic group of actors, ranging from a precocious eight-year-old girl to a heavy-set, Santa Claus-like older man. Mast uses activities like dictation, monologue, emoting on demand, and standup comedy to explore shades of human comprehension or the lack thereof. The video version is called an Addendum to the theater version; it does not document the entire performance, but rather extracts bits of it and uses aggressive camera angles to create a different experience—and yet another layer of semiotic exploration. The work seemed even more molecularized as a result, broken down into essential signs and codes, with no narrative threads in sight.

In a funny nod to LA stereotypes, Sophie Bonnet-Pourpet created Dear Aaron, The Wallpaper Has Some Existancial Problems (2013), a paper modernist house made from UV-sensitive wallpaper that the artist “tanned” with sunlight, with the intention to present it as a gift to TV producer Aaron Spelling. Simon Bergala made a series of abstract oil paintings on the backs of padded jackets (all 2012) that were meant to be worn as street performances. On the day that I visited, a sign hung in the place of one of the jackets, reading “Untitled (Red Hood) is today ‘walked’ on Sepulveda Blvd. Los Angeles (from LAX to North Valley).”

Simon Bergala. “Untitled (purple),” 2012. Courtesy the artist and LACE.

The most surprising choice made by the curator was Andrea Fraser’s Official Welcome (2001/2003) performance, presented on video, accompanied by her sculptural installation, Un Monumento às Fantasias Descartadas (A Monument to Discarded Fanstasies) (2003). The former finds the artist at a podium performing banal and ridiculous remarks, both real and fictional, given by art world types during awards ceremonies; considered part of her institutional critique work, it skewers the posturing and smugness that occurs at such events. The latter consists of a tall pile of discarded Carnival costumes from the streets of Rio de Janeiro; almost a material counterpoint to the painful sterility of the video, the costumes speak more honestly of disposable identities and are at once wistful and defiantly exuberant.

One would not ordinarily think of Andrea Fraser and Guy de Cointet in the same breath, one being so aggressively articulate and pedagogical and the other remote, formal and indecipherable. And yet, to make this association suddenly feels both natural and illuminating. Both artists use texts and colorful objects as interchangeable props within a trickster’s narrative. Both take a certain amount of joy in the miscomprehension of their audience, finding success when they upend deeply held expectations for structure and decorum. Through inventive associations like this, de Brugerolle makes a winning leap from obscure specifics to persuasive universalities.