Advertisement for “The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things,” Nottingham, 2013. Photo: Natalie Musteata

Last week, I embarked on a month-long research trip through Europe to continue my dissertation study on the history of artist-curated exhibitions. First stop: London. During my four-day stay I visited the Barbican Center, where I saw The Bride and the Bachelors: Duchamp with Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns. This stunning exhibition, curated by Carlos Basualdo and staged by French contemporary artist Philippe Parreno, traces the impact of word-punning modern master, Marcel Duchamp, on the work of four preeminent and interconnected artists of the 1950s and 1960s. I also made a stop at Tate Modern, where three retrospectives are on view: the first large-scale museum survey of the long-overlooked Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair, student of the French painter Fernand Léger, and a pioneer of abstract art in the Middle East; a mid-career review of American artist Ellen Gallagher’s twenty-year oeuvre; and an overview of the career of American Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein. But it was off the beaten track at Nottingham Contemporary, one of the largest contemporary art spaces in the UK, that I found the real gem of my trip.

On a chill overcast morning (which, from experience, describes most days in the UK), I took the two-hour train from St. Pancras Station to Nottingham (a modest city perhaps best known for its link to the legend of Robin Hood) to see The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things, an exhibition organized by the 2008 Turner Prize-winning artist Mark Leckey. It did not disappoint.

Mark Leckey. “The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things” at Nottingham Contemporary, Gallery 1, 2013. Photo: Natalie Musteata

The latest in the Hayward Gallery’s traveling series of shows curated by British contemporary artists (a program initiated in 1991, when Deanna Petherbridge installed The Primacy of Drawing: An Artist’s View), Leckey’s exhibition draws on a wide range of material, both historical and contemporary, utilitarian and artistic to consider the “magical world of new technology.” In particular, Leckey is interested in exploring the moment of change we are currently experiencing with the rise of the Internet and digital media—technologies that have started animating otherwise lifeless “things.” For example, smart fridges can now provide recipes and even turn themselves on and off; iPhones come equipped with Siri, a robotic female guide; and Google Glasses function as quasi-extensions of our brains.

The exhibition is installed in four galleries around a set of loosely configured themes: “Mankind,” “Animal Kingdom,” “Vegetal World,” and “Technological Domain.” Some themes overlap as they span multiple galleries. The first room’s display, a black box immersive environment, is visually the most atypical. Arranged on black pedestals and dramatically spotlit, the works and objects relate to legendary monsters and science-fiction fantasies that suggest the confluence of man, beast, and machine. A dilapidated stone bust of a Minotaur; a sixteenth century mandrake root carved to enhance its human resemblance; and a sexually polymorphous headless creature by Louise Bourgeois are but a few examples. Aurally enlivened by Florian Hecker’s electro-acoustic video piece Chimerization (2012), this room also includes four larger-than-life size phosphorescent drawings of mythological figures in various stages of historical evolution: a cave man with club in hand, drawn in 2012 by French illustrator Thibaud Herem, is juxtaposed with Francois Dallegret’s 1968 schematic design for a cosmonaut suit for a Vitruvian man of sorts.

Mark Leckey. “The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things” at Nottingham Contemporary, Gallery 2, 2013. Photo: Natalie Musteata

Mark Leckey. “The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things” at Nottingham Contemporary, Gallery 3, 2013. Photo: Natalie Musteata

The second gallery is subdivided into at least three distinct presentations, the most compelling of which features works of isolated body parts systematically organized within an effulgent green space. For instance, a silver hand reliquary from the thirteenth century is placed adjacent to Touch Bionic’s I-limb Ultra (2012), the most technologically advanced prosthetic hand on the market today, while on a higher register, three heads, including a Cyberman helmet from the BBC series Doctor Who (c. 1985) and a Singing Gargoyle sculpture from England (c. 1200) are placed side by side.

Unlike the former two galleries, which maintain a certain amount of visual diversity, the latter two are slightly more uniform and conventional. The third room, for example, focuses on works that draw on the mechanics of automobiles, while the fourth explores the world of animals and includes not only a colossal inflatable Felix the Cat—the first cartoon image ever transmitted on television—but also a zoo-inspired panorama with a cardboard cutout of a Max Ernst painting.

Mark Leckey, “The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things” at Nottingham Contemporary, Gallery 4, 2013. Photo: Natalie Musteata

The exhibition reads like a wunderkammer filled with natural oddities, contemporary paintings, sculptures, and mechanical toys. Residing in the interstice of the real and the virtual, the objects included “transcend their objecthood.” According to Leckey, what excites him “is the idea of treating [artworks] badly and not respecting them as individuals…discreet objects that have their own aura, in a traditional white cube gallery.”

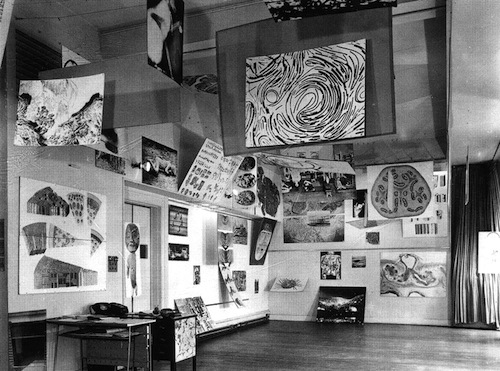

London has a rich history of artist-curated exhibitions, dating back to at least the Independent Group’s experiments at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art. This year, in fact, marked the sixtieth anniversary of the IG’s ground-breaking Parallel of Life and Art (1953), an exhibition featuring 122 photographic panels of images taken from newspapers and books of modernist paintings (Kandinsky, Picasso, Dubuffet), tribal art, children’s drawings, and hieroglyphs, as well as anthropological, medical and scientific photographs, which were hung without commentary at various angles and heights throughout the ICA. To commemorate the show’s anniversary, the ICA organized a two-day conference dedicated to the IG’s curatorial work—as well as a dishearteningly claustrophobic display of the group’s artworks, currently on view in the museum’s Fox Reading Room.

Nigel Henderson, Eduardo Paolozzi, Alison and Peter Smithson. “Parallel of Life and Art” at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, 1953.

This momentary overlap between these two otherwise distinct moments in the history of artist-curated exhibitions—that is, the IG’s experiments in exhibition design in the austere postwar period of the early to mid-1950s, and Leckey’s Google-driven twenty-first century foray into exhibition making—raises a number of questions with which I’ll close this first blog entry: How have artist-curated exhibitions changed or developed in the last six decades? And how do they compare to exhibitions organized by curators proper? More on this later.

Natalie Musteata is Blogger-in-Residence through June 28, 2013.

Pingback: Travelogue Entry No. 3 | Singularity and Repetition in Venice | Art21 Blog