In 2008, SuttonBeresCuller (SBC), the Seattle-based artistic team of John Sutton, Ben Beres, and Zac Culler, received a Creative Capital grant for their project Mini Mart City Park. This brownfield revitalization project aims to transform a derelict former gas station in the Georgetown area of Seattle into a living work of art, including a pocket park and green building, while preserving its old-time, filling-station aesthetics. SBC estimated the project would take about a year to complete. Then they ran into a massive environmental problem and a Dickensian net of paperwork, delays, and anxiety-producing legal ramifications. In the process, Mini Mart City Park, which began with what seems in retrospect to be rather modest ambitions, has evolved into a full-scale social project that is challenging environmental policy and creating an entirely new model for how communities can work collaboratively to transform contaminated sites in their own backyards.

Even if SBC wasn’t entirely sure what it was getting itself into, these artists are ideally suited to lead a project like this. They have been working together on interactive and site-specific constructions for fourteen years, since graduating from Cornish College of the Arts. As a longstanding collaborative, they have learned how to develop ideas jointly, through the friction of opposing perspectives, and are systematic in their division of labor. The level of complexity in Mini Mart City Park, however, has exceeded even the wildly imaginative scope of their previous work. It has endemic challenges, and it moves, stubbornly, at its own pace.

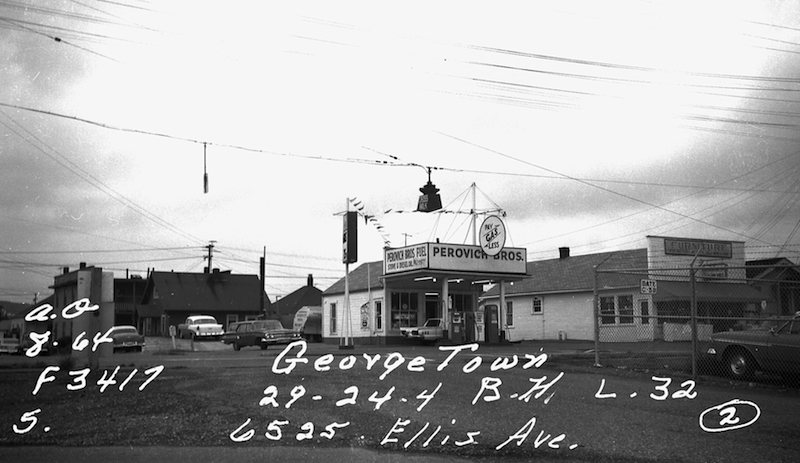

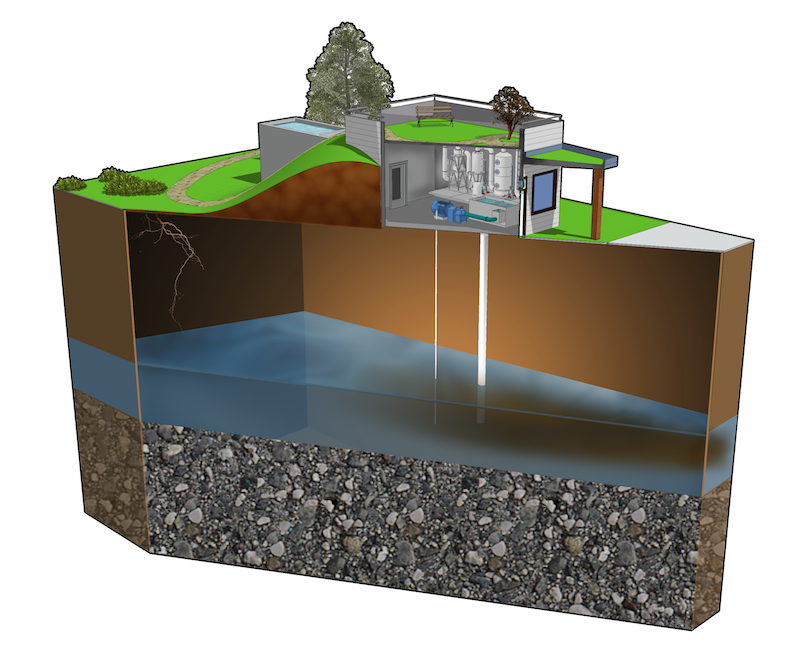

The first sign of trouble came after SBC had signed the lease on the property at 6525 Ellis Avenue South, did a surface cleanup, and drew up plans to extend the building. They then found themselves up against the city’s Department of Planning and Development, a permits thicket that made a temporary arts venue impossible. A two-phase environmental assessment revealed more extensive contamination than what had been assumed: the presence of petroleum, including diesel, in both the soil and groundwater. Built in the early 1930s, Perovich Brothers, in addition to being a gas station, stored forty thousand gallons of fuel in buried tanks for Boeing during World War II. In a 1970s incarnation, the site was home to a dry cleaner, further contaminating the area. SBC secured funding for another, more comprehensive round of tests with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). An underground hydraulic hoist was removed.

Five years had now passed; SBC had gone through four environmental assessments, a great deal of money, and multiple exhausting rounds with city bureaucracy. They were counseled from every side on the site’s nightmarish complications. They were spending a lot of time in meetings and were still very far from seeing their original idea take shape: to redesign, reconstruct, and repurpose the building. The smart thing would be to walk away from the site. Instead, in April 2013, SBC raised money and bought it, wedding themselves to the community, the fights, their contaminated little piece of land, for an indefinite period of time.

The original idea had, and still has, an element of the absurd: to utilize the aesthetics and therefore the history of gas station mini-marts to address an American culture that creates and supports them. Much of SBC’s work plays with visual assumptions, alternately provoking and engaging its audience. For The Island (2005), they built and then marooned themselves on a floating “desert island,” wearing ripped-up business suits, in sight of Seattle’s SR-520 bridge, tying up commuter traffic and riling local news outlets. For There Goes the Neighborhood (2005), SBC took a living room on an eight-stop tour of Seattle, inviting people in to watch television, talk, and look around; one of their many “family” portraits was hung above the mantel. The surreal, site-specific installation Small Moons (2012) featured enormous, intricately constructed floating spheres of domestic objects, working fans and lamps, chairs, maps, and games from Louisville homes that Louisville residents then re-encountered in a public space.

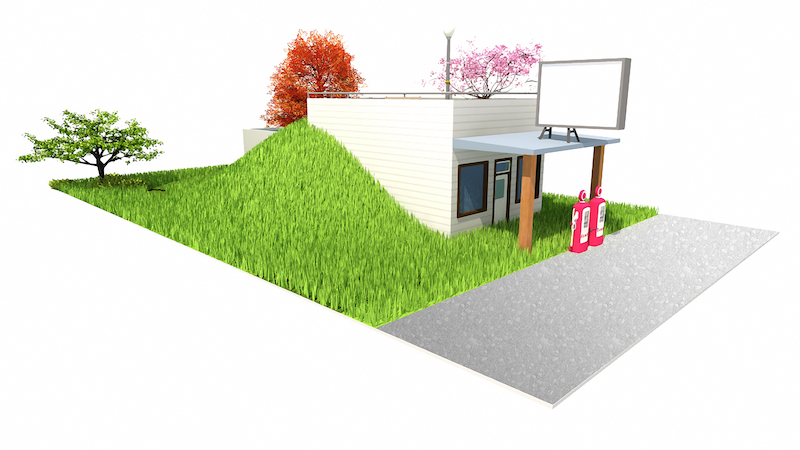

Now SBC has its community—not just as an audience but as collaborators. Along with the city, the EPA, environmental consultants, lawyers, and arts organizations like Creative Capital. They have established a nonprofit called Mini Mart City Park to apply for grants, shield themselves from potentially millions of dollars of liability, and maintain the site in perpetuity if the community or the parks department is unable to. The abandoned gas station will have to be razed, and SBC will salvage what’s possible: the window frames, the vintage sign. They have to excavate the contaminated soil to a depth of twenty feet, which would then typically be trucked to eastern Oregon in convoys, involving more petroleum. But SBC—now more educated and savvy about environmental issues—is lobbying to change the policy for smaller sites like theirs, in order to handle the soil remediation on site. They have become, as they say, “accidental activists.”

There are more than two hundred thousand abandoned gas stations in this country, the majority of them in low-income neighborhoods, which also have a dearth of green spaces and access to the arts. If it’s crazy to think a group of artists would take on a project like this, it’s crazier to think a fiscally minded entity would, given the massive cleanup costs, potential liability, and the high risk and low return of real-estate investment in a depressed neighborhood.

But artists learn through practice to see a narrower gap between an idea and reality than most people do; an artistic mindset is essentially a visionary one. Combine that vision with resourcefulness, the desire to seek challenges (instead of avoiding them), adapt to fluctuating circumstances, ignore censure, and the perseverance to see a project through—suddenly it’s not just an innovative mindset, it’s a solution-oriented approach. You see the same qualities in environmental and community activists, like those extensively involved with Mini Mart City Park. It is through these incredibly forceful partnerships that change occurs.

Mini Mart City Park, a project that seems to fuel itself on complications, has expanded. When complete, it will encompass a small park, public sculpture, and a green building, which will serve as a community center and a venue for local art exhibitions and music events. It will also serve as a template for similar sites nationwide, as it moves through the labyrinth of funding and policy and works with the city to develop the means to assist such civic-minded revitalization projects. Like with anything of consequence, first you create the project, then you create the blueprint for it.