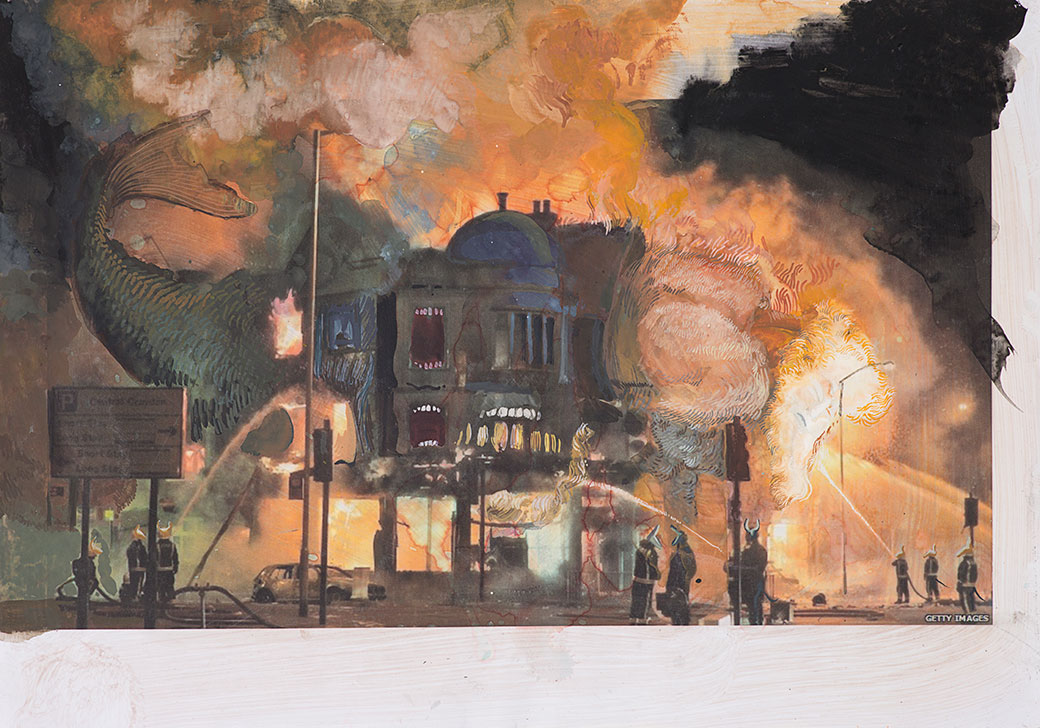

Rokni Haerizadeh. Subversive Salami in a Ragged Briefcase, 2014. Gesso, watercolor, and ink on printed paper; 11 3/4 x 15 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai.

Depictions of war have been seen for centuries in classical art, and works by Jacques-Louis David, Francisco Goya, and Pablo Picasso are some of the best representations of the ravages of battle during important periods in history. Yet the impact of war and the need for transformation has rarely been displayed with such urgency than in the spate of recent exhibitions showcasing art from the Middle East. The show Here and Elsewhere, at the New Museum, and several exhibitions of contemporary Iranian art in New York City have featured work made from the most excruciating personal circumstances with the most public ramifications.

Violence, devastation, and history often dictate these artists’ choices of medium. Their unconventional, non-monumental methodologies steer away from sentiment or propaganda as they take on the challenging subjects of identity, dislocation, and deracination. Issues of nationalism are embraced as artists from the Middle East make a powerful case for art that does not merely reflect troubled times as much as it gives shape to cultural identity. Their works make clear the importance to look at art from the region as game-changing in the way that viewers are affected.

Mosireen’s Tahrir Cinema during July 2011 occupation of Tahrir Square. Photo: HamnoT. Image via Wikipedia.

For the US-born, Cairo-based artist Sherief Gaber and other members of Mosireen, an independent media collective in Cairo, the innumerable videos posted on social-media outlets of the Egyptian revolution since the end of Hosni Mubarak’s three-decade rule on January 25, 2011, have become important tools for producing new environments of truth and authenticity. Generated by a passionate interest in social justice, videos such as The Martyrs of the Egyptian Revolution (2011) and Blood by Night, Grief by Day (2011) are made from raw footage of civilians being beaten, bulldozed, and ruthlessly eliminated by the military. With Gaber’s US training in urban planning and law, Mosireen’s work is geared towards the transformation of quotidian spaces. In We Empted Our Pockets Out of Joy (2013), ordinary streets where people were killed, tortured, and kidnapped during skirmishes with the police become important places and moments in history. Media activism is used by the collective to counter state-produced narratives and to broadcast a new form of nationalism centered on Egypt’s grassroots revolution.

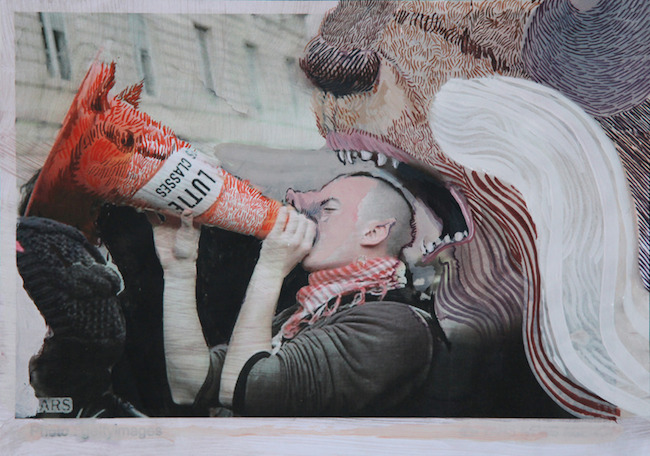

Rokni Haerizadeh. Fictionville, Some Breath Breathes Out of Bombs and Dog Barks, 2011. Gesso, watercolor, and ink on printed paper, portfolio of nine works; 8 1/4 in x 11 3/4 inches each. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai.

A different kind of truth telling emanates from the art of the Iranian expatriate Rokni Haerizadeh, who lives in Dubai. Deeply critical of the religious mullahs in his country who have stifled Iranian citizens since the 1979 revolution, his series titled Fictionville (2011) creates provocative portraits of a fundamentally flawed society. Inspired by Persian literature and ancient Indian allegorical tales, half-human, half-animal creatures inhabit his canvases to reveal the savagery of human nature. In this series, prints made from images from the news media and YouTube of worker strikes, women’s rights protests, and political uprisings in Iran are partially painted over. Grotesque figures being victimized, harassed, and arrested seem to squirm and move on the canvas; they trace experience in time, just like action paintings that leave the viewer with a sense of a gesture. In Haerizadeh’s work, anxiety from surveillance and the power of the media to control the populace drives a deep form of activism.

Ziad Antar. Murr Tower, Wadi Abu Jmil, Built In 1973 from the “Expired” series, 2009. Gelatin silver print; 19 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Selma Feriani Gallery, London.

The notion of home and identity is recontextualized in Ziad Antar’s photographs. Born in Saida, Lebanon, but based in Beirut and Paris, Antar has made faded black-and-white images that reflect on the accuracy of archival imagery and representations of colonial Lebanon. In the Expired Series (2009), Antar photographed abandoned structures and unfinished monuments after the 1975 civil war using expired film with a 1948 Kodak Reflex camera. These grainy, seemingly vintage photographs question the verity of images. Antar’s technique not only blurs the line between what one sees and believes but also creates an antiheroic stance that breaks with the tradition of monumentalizing colonial histories.

Viewers can experience a kind of transformation from such images that document, protest, and reexamine various ethnic, political, and authoritarian regimes that fundamentally alter these Middle Eastern states. In these exhibitions, artists from different countries come together in their shared purpose of presenting personal histories that symbolize a larger collective journey and identity—that ultimately communicate the significance of life. Such art evokes larger emotions and a transcultural sensibility that attests to its relevance in the world today.

Pingback: The Yams Collective: Insurrection and Resistance | ART21 Magazine

Pingback: Artel