Summer Wheat, “A Lady’s Dinner.” Oil paint and gorilla glue, on a dinner plate. 11″ diameter. All images courtesy of and copyright by Summer Wheat.

In my early twenties, I took Greyhound buses across the country, outfitted with my cassette tapes and philosophy books, in search of meaning. Traveling through North Dakota, I sat next to a woman with a white-wolf graphic on her T-shirt; she dragged black Hefty trash bags full of clanking dishes down the aisle. On another trip, I sat next to a six-foot-six-inch black man holding a tiny baby, close to his chest; the baby nearly fit in the palm of his hand. I never knew whom I would sit next to. It could be a runaway teenager, an avid fan of the band Tesla, or a middle-aged woman taking a pregnancy test in the bus restroom, who would learn she was, in fact, pregnant.

My books provided contrast to the surroundings. Kant, Hume, Hegel, and Plato filled the gaps as I surveyed America. My aim was to find a premise about art that I could subscribe to, but reading those texts seemed like digging a never-ending hole. It was an existential mayhem, one that paralleled the horror of the realization that one is essentially a cell within a cell, within yet another cell.

The passing landscapes blended together into one big pile of intellectual rubble. But Tolstoy’s treatise “What is Art?” cleared the way. In his essay, Tolstoy states, “If the artist is sincere, he will express the feeling as he experienced”; real art was “infectious” and would spread like a wild fire: “The stronger the infection, the better the art.” [1] As simple as it sounds, these two thoughts were all I needed to stop searching for something outside of myself. Suddenly, I became enough.

In the coming years, I’d rarely leave my studio, and I proceeded to create a countless number of failed paintings. Tolstoy’s essay had inspired me to stop looking so far outside myself for meaning and challenged me to translate what was within me. This initially seemed an easy thing to do. It definitely was not. In fact, it was gut-wrenching to work year after year—practically defeated—with only grey paint sludge to show for it. I regularly asked myself: How could I influence the world with my art? It seemed impossible. After all, who was I to think it should be so?

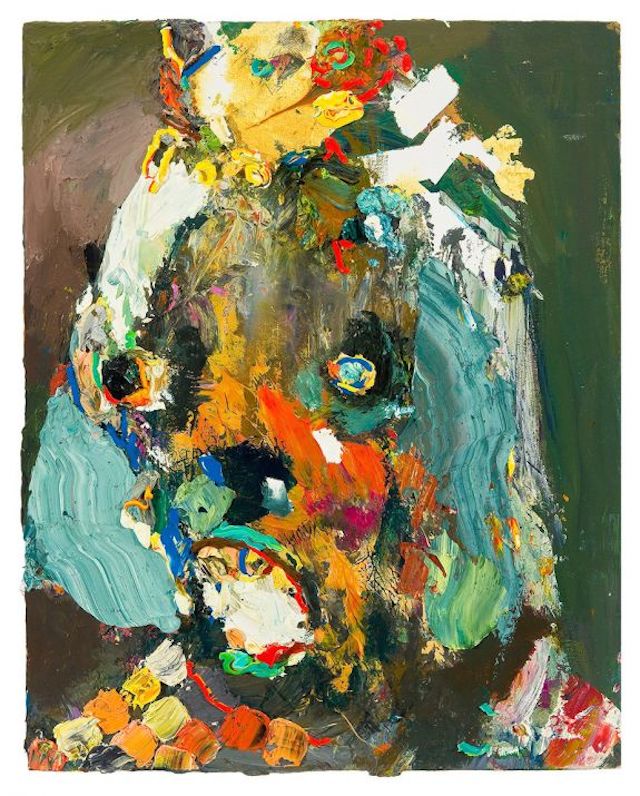

After an agonizing decade, I painted a series of zombie portraits, using debris removed from the still-wet surfaces of paintings that I considered failures. I viewed these paint scrapings as dead material. With my use of palette knives, sticks, and hand-fashioned extruders, the faces of these zombies began to emerge out of the matter. It was like magic, and making them was effortless. Suddenly I did not have to try so hard, and in resurrecting these dead paintings into new forms, I brought myself to life as an artist.

Late one night, my attention was drawn to a mound of excess paint on my studio floor. Pressing my fingers through it like clay, I produced a sculpture of broccoli. I affixed this broccoli to a dinner plate and hung the plate on my wall. The broccoli as an object was believable and motivated me to take the canvas out of the process. I then sculpturally reproduced everything around me that I loved—a wall tile, a shoe, a tapestry—all made out of paint. My perception of the material had permanently shifted. I needed to bring the paint out, into three dimensions, before I could bring visual depth to a flat surface. With all of these variations in form, I then felt allowed to establish an equation with materials inside a space.

Pulling the paint apart for inspection was like an analysis of my deeply embedded insecurities. There had been no shortcuts to finding myself this way, and what I learned from this experience is that there is no way out of yourself, only a path through yourself, toward sincerity. Tolstoy’s writing catalyzed this passage, and I have arrived at a place where the thought that we are all cells within many nested cells now converges with a certain freedom.

—

[1] Alex Neill and Aaron Ridley, The Philosophy of Art: Readings Ancient and Modern (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995), 508.