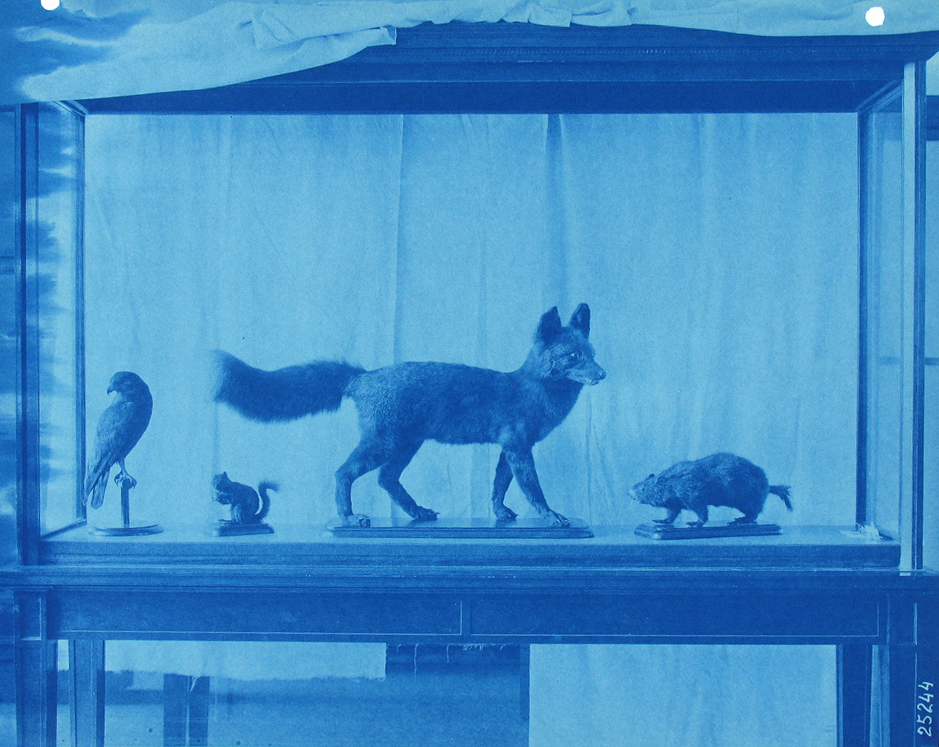

Thomas Smillie. Untitled, 1890. Cyanotype. Source: Smithsonian Institution Archives.

This text is from a forthcoming collection of short stories about speculative museums. “Janitor for the Nation” was born from an invitation uttered during a performance by Public Movement:

“Imagine that this museum is a nation, and inside this nation is a museum.”

Each nation lasts about as long as an average exhibition, eight to twelve weeks. On the evening that the current nation closes, its flag, sewn only weeks ago, is slowly lowered and the anthem sung for the last time. No need for a coup d’état. Those with positions in the administration, who’ve barely slept in their short run of the nation, are happy to return to their homes. A new president is elected by the following weekend, and a new constitution ratified before the full moon. Only those present in the museum during the transition of power may vote and be called citizens. Passports are issued, and customs officials replace box-office attendants, gallery guards are transformed into the national guard.

Each new nation spends much of its brief existence in formation. The inauguration ceremony of the president and the naming of the nation can take five minutes or five days. Electing a parliament and appointing cabinet members can happen in an afternoon or take weeks. Some decisions are made by presidential decree, like the temperature of the air conditioning or the nation’s open hours, and others by subcommittee, like the guards’ uniforms or the official cuisine, which is served twenty-four hours a day in the cafeteria. Some nations commission paintings of the founding fathers, others merely post their photos on social media.

The greatest challenge for each nation is how to schedule the use of space. The citizens writing the anthem need space to rehearse while the military wants to run a fire drill. The nation’s doctors require a place for their clinic, and of course the museum, which has been reduced to a couple of galleries, needs more storage for the nation’s collection. Negotiations can be fierce and occasionally lead to civil wars, which tend to involve half the population sleeping in the basement and the other half on the roof, where small sleeping cabins were constructed in the early years.

All those present during each nation understand that it will come to a close, that their nation is a form of theater. The primary audience is also performing (as citizens or the administration), in addition to daytime visitors or the occasional immigrant. One may argue that this performance of a nation is no different than the construction of a government in any country. The more the performers believe it’s real, the more real it becomes. The limits of the performance are tested when a visitor breaks the law and is held in jail, awaiting trial. If the case makes it to trial—it can take weeks to appoint judges—the sentence may be as much as two or three years, but everyone knows that the sentence will be no longer than the run of the exhibition. When the penalty is minor, the janitor will unlock the cell and ferry the visitor out the rear exit, with a reminder not to return for a couple of months, at least.

Over the years, the museum has hosted many visionary leaders who, knowing that their nation won’t last, risk experimental formations or ambitious construction projects. One nation, speculating about natural resources, successfully dug a subbasement. Another sustained a lawless state by making only two laws: mandatory nudity and a ban on making laws. While this was one of the more popular nations, attracting thousands of daytime visitors and a record number of immigration requests, some on the outside argued that this was not a nation at all, just a temporary nudist colony. One president refused to delegate decision-making authority, packaging a temporary dictatorship as the production of a gesamtkunstwerk. Another choreographed the movements of the entire administration as a dance. As a result of these experimental nations, the Museum of Nations (as it’s often called beyond its walls) has been the subject of important case studies, referenced by political philosophers and international-relations specialists worldwide.

The only individual who has endured every nation, from the very first, is the janitor. He alone persists, excepted from the national agenda, as the primary caretaker of the outdated electrical system and faulty plumbing. He keeps a small bedroom in the darkest corner of the subbasement. While he doesn’t aspire to power, he has been known to host the standing president at his small kitchen table for midnight conversations. More than anyone, he has witnessed the failures and triumphs of past nations. He’s heard every speech, mopped up blood from conflicts, and has occasionally served as an arbitrator between outgoing and incoming administrations. Because he finds valediction awkward, he’ll often hide in the subbasement or sneak out to a movie theater in the last days of each nation. His own departure, and implicitly his retirement, was handled in a similar manner. One day he was simply gone. With him he took a ten-year collection of passports, copies of every inaugural address, recordings of every anthem, and the flag of each nation. These he sold to another museum, and with the sum he moved to a small cabin with a view of the Mediterranean Sea. There he lived out his days, making an occasional visit to the nearest nudist colony. He never touched a mop again.